Japanese Peruvians

Like many Americans, I knew that 120,000 ethnic Japanese had been held in U.S. concentration camps during World War II. But I had no idea about a secret program that had kidnapped thousands of ethnic Japanese in Latin America and delivered them to concentration camps in the States with the help of compliant Latin American governments. I discovered this startling historical episode while researching for a book on World War II in Latin America and decided to track down people who might have been affected by the secret program. I got an unexpected lesson in how history can live literally around the corner.

“Yes, I live two blocks away from you,” said Kazumu Naganuma, a seventy-six-year-old graphic designer and active soccer coach. On the afternoon of our first interview in 2016, Naganuma and two of his brothers, all Peruvian-born, walked over to my house in San Francisco. For hours they recounted their childhoods and described how their father and an older brother escaped to mountains outside Lima when detectives came to their house in Callao, Lima’s port city. By then, in early 1944, everyone in the Peruvian Japanese community knew what might be in store for them when strange men appeared at the door. Eventually the Naganumas’ father, Iwaichi, surrendered, and the whole family, mother (Isoka), father and seven children were taken off to the United States.

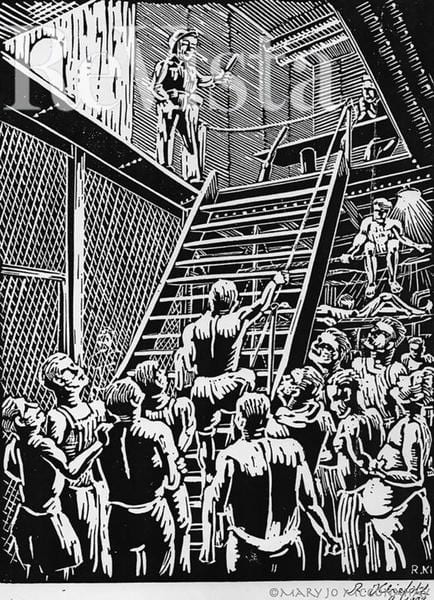

The Naganuma brothers, baptized Catholics as Jose Antonio, Jorge Carlos and Julio Cesar, and their parents, in Peru called Luis and Maria, had been part of a vibrant Japanese Peruvian community of 30,000 persons. Kazuharu Naganuma (the brothers prefer to use their Japanese names now) joyfully remembered a big yard at their house with an attached commercial laundry, “all hand wash, with big paddles and metal tanks and clothes and sheets hanging outside and a sewing room to make repairs.” They spoke Spanish. Another brother, Kazushige, remembered how his older sisters once treated him to an animated movie that made fun of Japanese, featuring a General Tojo-like figure wearing big black-rimmed glasses, “with buck teeth” and other stereotypical features (perhaps You’re a Sap, Mr. Jap, from Paramount). “I went home and talked about it, but I wasn’t offended,” Kazushige said. “I was thinking of it as a Peruvian kid.”

There were many more Peruvian kids like him. It did not matter if the Latin American residents were native-born or naturalized citizens of the countries from which they were seized. The given justification: to prevent a fifth column from sabotaging the Allies.

The real reasons for the U.S. program included racial prejudice and the assumed allegiance of Latin American Japanese to Japan, with which the Allies competed for raw materials. Most egregious of all, Washington needed “Japanese” individuals to exchange for certain prisoners of war—U.S. civilians stranded in Asia. Called Quiet Passages, the secret program run by the U.S. State Department Special War Problems Division considered Latin American Japanese ideal pawns to trade for the trapped U.S. citizens. They were perceived to possess even fewer claims to rights than imprisoned Japanese Americans, most of whom were U.S. citizens.

Ethnic Germans and some Italians from more than a dozen Latin countries were also forcibly brought to U.S. camps, but unlike these captives, most of the Japanese were unable to return to their Latin American homes after the war. All were purposely stripped of their identification papers on leaving the Latin nations where they lived. They arrived in the United States as “undocumented enemy aliens.”

After I talked to the Naganumas, I visited other former detainees over the next months. They remembered being shuttled onto U.S. ships in Latin ports under U.S. military guard, delivered to New Orleans or San Pedro and transferred to a prison camp called Crystal City in the hot Texas desert. There they lived for years surrounded by barbed-wire fencing and watchtowers, subject to daily muster. For these conversations I never had to drive more than an hour from my home. A largely unrecognized face of the Latin diaspora, I realized, might be found in our own backyards.

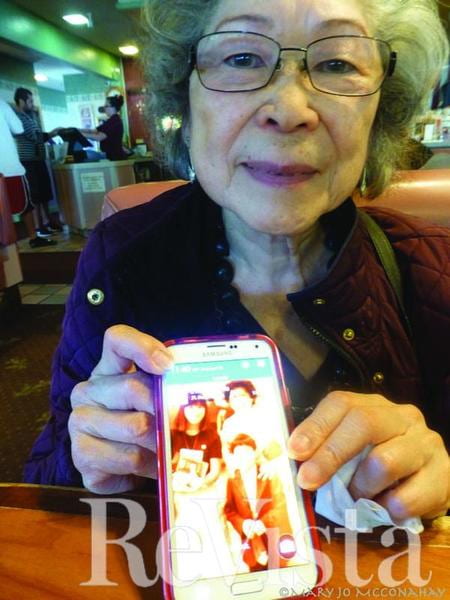

Libia Maoki, who is retired from a position overseeing charters for a long-distance bus company, sat across from me over coffee in a strip-mall diner outside Sacramento and recalled herself as a young girl in Chiclayo, Peru, five hundred miles north of Lima. There, in semi-tropical surroundings, Libia helped her mother, Elena, an industrious woman who had been a nurse in Japan, to pull taffy and wrap it in paper for sale. Her father, Victor, ran a sugar plantation canteen and a tire-repair shop. Libia watched agents sent by the FBI arrest her father and take him away, standing in a truck bed with other Japanese men and some ethnic Germans. Bereft of their breadwinner, Elena Maoki and her children were granted permission to go to the States, as long as they too became prisoners in Crystal City. Like many of the Japanese targeted for kidnapping, Libia’s father and Iwaichi Naganuma, the father of the Naganuma brothers, were prominent in the community and had founded local schools. “In Peru they were preparing us to be leaders. So it’s really too bad they got rid of us,” Libia’s sister Blanca once said to an interviewer.

Of 2,200 ethnic Japanese forcibly taken from Latin nations during the war, 1,800 were from Peru, a country which had exhibited a history of animus toward Japanese immigrants. In May 1940, an anti-Japanese march by teenage students in Lima sparked rioting in the capital and small cities; rowdies and ordinary neighbors trashed or burned six hundred homes, schools and businesses while the police stood by. Ten Japanese people died. Later the U.S. embassy official charged with identifying threatening “aliens,” John Emmerson, used Chinese collaborators to point the finger at suspect Japanese, effectively playing one minority group against another. When the war was over, Peru refused to take back those who had been removed.

In the end six hundred “Japanese” prisoners from Peru were deported from U.S. camps to the ancestral war-torn island, where many had never lived. Other families were forced to stay in Crystal City for up to two years after the war was over—in a Kafkaesque scenario, U.S. authorities officially regarded the prisoners as illegal aliens for having entered the country without documents, and they had no place to go. In 1947 the Naganumas, worn out and some suffering from tuberculosis, left Crystal City under the sponsorship of a Shinto priest in San Francisco.

Today camp survivors, and their children and grandchildren into the thousands, live scattered across the United States, many in New Jersey, because some captives chose “parole” to a company that produced frozen vegetables in a rural township thirty miles south of Philadelphia, and families stayed in the area. Others gravitated to Chicago, Los Angeles or Northern California where Japanese Americans were trying to rebuild lives. A number of Japanese Peruvians found postwar racial prejudice too strong on the mainland, and moved to Hawaii.

In San Francisco, the Naganuma brothers were enrolled in school as Jimmy, George and Tony. Speaking English with a Spanish accent and looking Japanese, they said new friends doubted their story when they shared it. “They would say, ‘That could not have happened—how could they get away with it?’” said Kazumu Naganuma. “People don’t believe it happened. It’s not in the books.”

Fall 2018, Volume XVIII, Number 1

Mary Jo McConahay is the author of The Tango War, The Struggle for the Hearts, Minds and Riches of Latin America During World War II (St. Martin’s Press).

Related Articles

From Vendedor to Fashion Designer

English + Español

Korean immigrants in Latin America are shaping and developing fashion economies there. Upon arrival, Korean immigrants to Argentina and Brazil may have been lonely, isolated and confused…

Shared Sentiments Inspire New Cultural Centers

English + Español

In the early afternoon of January 3, 2018, in the mountainous village of Shicang, Zhejiang Province, China, firecrackers burst into the air and flags waved in the wind as a parade of Clan…

Evidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st Century

A Review of Evidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st Century Contemporary Human Rights and Latin America On September 5, 1921, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, Hollywood’s then best-paid star, attended a party in San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel, drank...