Latin America at the Century’s Turn

Putting Cuba 2000 in Regional Perspective

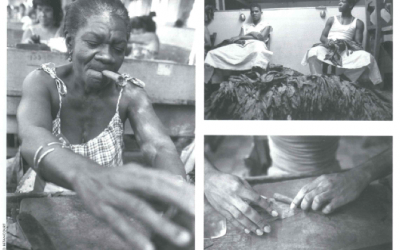

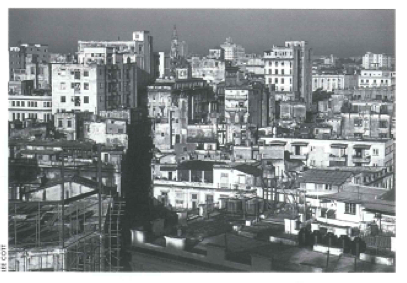

Havana scenes

It is hard to be upbeat about Latin America at the present moment. Although only two or three years ago, many observers maintained that sustained economic development and stable democratic governance were within reach there, hopes for achieving these goals any time soon have been receding. A cautious, skeptical, even pessimistic mood has been growing in and about the region.

This discouraged mood about Latin America no doubt reflects the past year’s bleak economic indicators. After achieving 5.2% expansion in 1997, the second highest rate of annual growth in 20 years, Latin America’s economies had fallen to 2.3% growth in 1998 – only half a percent above the rate of population increase – but 1999 was considerably worse for most countries. Taken as a whole, Latin America and the Caribbean registered no growth for 1999, equivalent to a 1 % reduction in GDP per capita.

But even if Latin America does rebound, the region’s overall economic performance is lackluster, as compared with the expectations aroused early in the 1990s. Despite the much-touted economic reforms in Latin America and the Caribbean during the decade just past, the average rate of annual economic growth for the region as a whole during the 1990s was less than 3%. That is about half what it was in the 1960s and 70s, and well below the 5-6% rate needed to reduce poverty. Although the share of Latin Americans who are officially regarded (according to United Nations statistics) as at poverty levels declined from 41% in 1990 to 36% in 1997, even that percentage is as high as it was in 1980. Some 200 million Latin Americans are still living in poverty.

Income distribution, long more unequal in Latin America than in any other world region, has become even more skewed. 10% of Latin America’s population receive 40% of income; the poorest 30% receive but 7.5%. The gap has grown between the fast caste – with their cellular phones, Internet connections, walled homes, and private security guards – and those mired in deprivation.

Although elected presidents rule in every Latin American country but Cuba and Paraguay, effective democratic governance is unambiguously strong only in Costa Rica and Uruguay — where it was well established forty years ago. Personal insecurity, pervasive corruption and endemic impunity are grim realities in much of the region.

Latin America’s immense challenges were often downplayed in the glow of satisfaction about the region’s turns toward economic reform and democracy. The U.S. government, in both Republican and Democratic administrations, talked of “the world’s first democratic hemisphere” (except for Fidel Castro’s Cuba, as Washington always emphasizes). Other observers trumpeted the supposed regional wave of democratization that would arguably create a more uniform and congenial hemispheric environment.

These flattering portrayals of Latin America oversold what was actually happening in the region, however, by glossing over major difficulties and differences.

There is today an opposite danger, that Latin America’s immediate problems may be exacerbated by broad-brush negative assessments. Latin America’s bad press could accelerate a withdrawal of international capital or make it prohibitively expensive, thus reinforcing financial instability. Financial turbulence, in turn, could drive parts of Latin America into depression, with negative consequences not only for Latin Americans but for the United States. Self-fulfilling prophecies of declining economies and growing instability could occur.

The disconcerting gap between yesterday’s rosy projections and today’s gloomy appraisals of Latin America in general derives primarily from four sources: exaggerating the pace of economic reform and democratization; underestimating the impact of exogenous pressures that have thrown Latin America off track; insufficiently disaggregating a vast region with internal distinctions as great as those within Europe and Asia; and inadequately recognizing the central roles of equity, education, and governance in shaping Latin America’s present and future.

Latin America’s moves toward free market economics and integration into the world economy were indeed important paradigm shifts, but they were not panaceas. After two generations of import-substitution industrialization and an ever larger state role in economic production – in many ways quite successful in promoting the region’s growth until the late 1970s – most Latin American economic policy-makers came to share the view by the middle to late 1980s that to grow further Latin America would need to prune the state’s economic activities, privatize production and distribution, attract foreign investment, emphasize exports, and open itself to international competition. These were major conceptual changes, with considerable practical implications, but they could not and did not all have immediate positive impact.

Governments find it nearly impossible to sustain popular backing for programs that may only slowly strengthen the aggregate economy, and that seem at first to enrich only a privileged few, without providing a credible promise of broad prosperity. Millions of Latin Americans who thought they had entered the middle class have found their real incomes ground down by recession and austerity measures, thus eroding support for reform programs. Strong social safety nets and improved public services might make the first-generation structural reforms more broadly palatable, yet these are hard to achieve because the reforms themselves and years of low growth and fiscal crisis, cut back the state’s capacity to deliver social services. Measures to restore fiscal balance in the late 1980s and early 1990s required cuts in social programs that are only now being rebuilt.

What its critics call “savage capitalism” is under attack in many countries throughout Latin America, but no broad agreement has been reached on an alternative policy framework. A full-court reversion to statist approaches, demagogic populism, and fiscal irresponsibility is unlikely, but so is unrelieved application of neo-liberal orthodoxy. Instead new approaches are beginning to emerge, rooted in market economics but including a stronger state role in improving and extending education, public health, and social services – and in alleviating poverty and reducing inequality.

It remains to be seen, however, whether detailed and coherent “third way” programs that foster economic expansion together with improved equity can actually be designed and successfully implemented, and where the resources will come from to undertake what is promised. Populist appeals and programs may yet emerge, probably with negative consequences for both foreign and domestic investment.

Because of major differences among the region’s countries, business and public policy decisions must be much more specifically calibrated than familiar discussions of “Latin America” permit.The nations of Latin America and the Caribbean always have varied a lot, and this divergence has been increasing, not narrowing, along three important dimensions: the degree of economic and demographic interdependence with the United States, the extent to which countries have committed themselves to international economic competition, and the strength of the state, especially in relation to organized crime and guerrilla violence.

The long-existing differences between the Caribbean Basin region on the one hand and South America on the other have been very strongly reinforced in recent years. The Caribbean Basin Initiative of the Reagan Administration and then the ongoing “silent integration” between Mexico and the United States spurred by NAFTA have been partly responsible for this reinforced bifurcation,. However, these measures are more consequences than causes of an ongoing, long-term process of functional integration – economic, demographic, social, cultural, and to some extent even political – between the United States and its nearest neighbors.

The functional integration of the Caribbean and Central American nations with the United States is less widely noted than that of Mexico, but equally dramatic. U.S. exports to the Caribbean Basin Initiative countries rose by more than 200% from 1983 to 1997, reaching $19 billion, almost $6 billion more than exports to China. That figure is also higher than U.S. exports to Argentina, Russia, or all of Eastern Europe – and this is all before NAFTA parity legislation, which would significantly further expand Caribbean Basin trade.

The demographic reality of Caribbean Basin interdependence is also striking. It is well known that some 10% of Cuba’s population has come to the United States since Fidel Castro took over, but immigration from the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Jamaica account for 12, 14, and 15% of those countries’ populations, respectively. Los Angeles has become as linked to Central America as is Miami, in many ways the capital of the whole Caribbean Basin region. Central American and Caribbean immigrants in the United States provide the largest source of foreign exchange to their home countries through remittances, but they also bring home crime and gang warfare. Politics and culture between the home countries and the U.S. mainland are increasingly intertwined.

Despite Latin America’s vast diversity, the region as a whole faces broadly shared challenges and dilemmas.

First is the central problem of equity – the vast imbalances of wealth, income and power that have long characterized most of Latin America and the Caribbean, and that at least for the time being have been exacerbated, not alleviated, by the market reforms of the 1990s. The divisions in Latin America have widened, although it has become unfashionable to talk about class struggle. Even if the most optimistic international agency projections about Latin America’s growth in the next decade turn out to be correct, income distribution may worsen. Unaddressed, that polarization could spell eventual social and political dynamite, especially where resentment about gross inequalities is heightened by rampant corruption, crime, personal insecurity, and evident impunity. Programs to alleviate extreme poverty, improve tax collection, facilitate credit for micro-enterprises, and provide broader access to social services are all crucial for Latin America’s future.

Second, closely linked with the problem of equity, is achieving improved accountability and the more consistently implemented rule of law. Neither political democracy nor market capitalism can develop well without independent judiciaries, civil control of the armed forces and police, broad access to information, autonomous and effective regulatory agencies, and other institutional constraints on power. More than economic policies, investment, and physical infrastructure, the “software” of effective governance is key.

Third, there is a growing consensus in Latin America that expanded political participation, stronger growth, and improved equity all depend on major improvements in education. Substantially increased and well-targeted investments are needed to assure that the changing technologies of the world economy do not leave further and further behind an underclass of the uneducated. It is crucial to improve basic education; upgrade teaching and standards; make secondary education more widely available, especially for girls; train and retrain workers for a more technological economy; and redirect resources from upper-class entitlement programs to those with broad benefits.

The region also faces thorny trade offs. It is not easy to balance the gains from interdependence with the costs to autonomy and sovereignty. It is hard to reconcile the advantages of global economic and political integration and the risks of vulnerability. The requirements of capital accumulation (and investment) and those of equity sometimes conflict. So do the imperatives of political and economic liberalization, for the demands of economic elites and the claims of an impatient populace are contradictory, at least in the short and medium term. It will take superb political craftsmanship to build and maintain the coalitions necessary to manage all these tensions successfully, and that skill remains in short supply everywhere.

Cuba in Regional Perspective

Cuba’s situation at the century’s turn is both remarkably similar to and profoundly different from that of the rest of Latin American and the Caribbean.

It is similar primarily because Cuba’s economic performance in recent years has been so disappointing and because Cuba -after forty years of vigorously asserting its national autonomy and sovereignty – still remains so vulnerable to international factors and natural disasters. It is also similar because Cuba, coming from such a different background and direction, is struggling like the region’s other countries to balance the requirements of capital, including foreign investment, with those of social programs and equity considerations. Throughout the Americas, including Cuba, countries are groping to fashion a way to use market instruments of capital accumulation and investment while being attentive to social problems and goals in ways that markets do not by themselves assure.

But while most Latin America and Caribbean nations face the challenges of equity, education, and governance as the hitherto insufficiently addressed agenda for the coming years, Cuba has done relatively well during the Fidel Castro period at confronting the challenges of education and equity. Cuba today has greater social and economic equality and a better-educated population than most other countries of the region.

Cuba’s critical challenge for the early 21st century is the issue of governance. Whatever his flaws and merits, Fidel Castro is certainly an authoritarian ruler whose prolonged reign has stifled political and social institutions, repressed political and civil rights, undermined the rule of laws and weakened accountability to any standard but his own approval. More than most countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, Cuba faces the need to construct viable political institutions.

An interesting question for the early 21st century is whether Cuba will continue to be an exception to the general trend of Caribbean Basin nations to become ever more integrated – economically, socially, demographically, culturally, and politically – with the United States. My own guess, for what it is worth, is that Cuba after Castro will return to a close association with the United States. I expect, or at least I hope, to attend major league baseball games in Havana before too long.

Winter 2000

Abraham F. Lowenthal is the founding president of the Pacific Council on International Policy an independent and nonpartisan international leadership forum, headquartered at the University of Southern California (USC) in Los Angeles. A professor of international relations at USC and also a vice president of the Council on Foreign Relations (New York), Lowenthal was the founding director of the Inter-American Dialogue, the premier think tank on Western Hemisphere issues, and before that of the Latin American Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington. He prepared this essay as a Visiting Scholar at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard.

Related Articles

Isabelle DeSisto: Student Perspective

encountered the first obstacle of my trip to the Isla de la Juventud before I even left Havana. Since American credit cards don’t work in Cuba, I couldn’t buy my plane tickets online. But that…

Honoring Humanity: An “Interview” with Richard Mora

Mauricio Barragán Barajas: Why don’t we begin by having you introduce yourself? RM: Alright. I was born in East Los Angeles, and grew up in Cypress Park, a barrio in…

Tobacco and Sugar

“Tobacco and Sugar” is the course that focuses American literatures on the Caribbean, and that acknowledges the unavoidable importance of monocultures for cultural studies. Much of the…