Latin American Art

Politics, History and Aesthetics

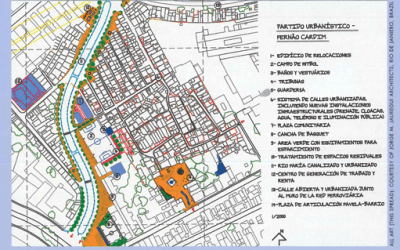

Convent School of San José, Feather Painting of the Mass of Saint Gregory, Mexico City, 1539.

As an art historian, I find it hard to believe that there could be many places in the world today where there is more at stake about art than there is in Latin America. In fact, Latin America, since its beginning in 1492, has been a struggle over images, whether they are licit or illicit, proper or improper, orthodox or heterodox, esteemed or not. One can never get very far away from the political, religious, economic, and cultural intensity that circulates around images, in particular concerning their creation/destruction. Columbus, of course, was never convinced that what he saw was anything different than what he already knew. But even after the revelation that the Americas were something new and therefore unknown, it became part of the Old World and known through presaging and then mirroring the great iconoclasm of reformation Europe.

In 1519, scarcely a year and half before the first acts of Protestant iconoclasm in Zurich, Cortés on his march from Veracruz to Tenochitlan stopped along the way to pull down and destroy the Mexican religious images and sculptures so as to set up in their place paintings and sculptures of Christ and the Virgin Mary. Cortés’ actions marked a very different iconoclasm than that called for by Zwingili and other Protestants. For Catholic Spain in the pagan New World, images were not in and of themselves at issue, rather what and how they represented was the problem. The disputation that Cortés initiated on the mainland established a defining debate in Latin America, a distinction between what was a truthful (Christian) and a false (Satanic) image, the distinction between latria and idolatry.

Thus, new images replaced or competed with old ones, giving rise to remarkable works of art by native artists whose abilities were compared to Michaelangelo and Berruguete by the soldier chronicler Bernal Díaz del Castillo. One need only look at a feather painting of the Mass of St. Gregory made in Mexico City in 1539 as a gift for Pope Paul III to understand what Bernal Díaz was referring to (Figure 1). Here one sees the talents and artistry of pre-Columbian Mexico turned toward creating an image that explicitly acknowledged the capacity of the Aztecs to recognize the fundamental mystery of transubstantiation. Equally, Andean artists, trained in European techniques, painted portraits of the Inca kings that were sent to the Spanish King, Philip II, who saw them hung in a royal chamber next to Titian’s great portrait of Charles V. At the same time, bonfires set in the main plaza of Mexico City by order of the city’s first bishop consumed numerous Aztec screen-folds of bark and hide that pictured both sacred and historical knowledge. Or, the golden image of Inca sun god was captured by the grand-nephew of Ignacio de Loyola and sent to Spain where it seems to have been melted down, perhaps to help finance other, more local wars. In its place, the great solar-shaped gold and jeweled monstances stood on the altars or were processed through the streets of the great baroque cities of Peru and Mexico (Figure 2).

A sense of this history, as sketched above in anecdotes, is necessary in order to understand why Latin America has such a remarkable and varied but conflicted artistic legacy, a legacy that today is often at the center of international politics, ethnic struggle, public policy, national identity, and religious focus.

Cultural patrimony, for example, is a current issue in Peru, Colombia, Mexico, Guatemala, Bolivia and many other nations, that often revolves around pre-Columbian and colonial works of art. The recognition of the public importance for these works of art is, however, more than just some abstracted notion about guarding national treasure from the international market in antiquities, although it is that too. One need only visit a looted archaeological site to realize how much information is irretrievably lost as a result of the search for a fine Maya pot or a Paracas textile (Figure 3) for the market place, placing the archaeologist and collector at odds, with the art historian somewhere in between. Yet, economic conditions often place local peoples in situations such that looting is a critical means of survival.

Pre-Columbian and colonial works, however, can be something much more than just some source of income, and this value brings local traditions and beliefs into conflict with the forces of the art market. In communities for which images have an honored place of veneration, their loss is not just about patrimony, a transgression of the nation. It is a loss of aura that can not be replaced, and such a loss gravely wounds the community’s sense of being, leading toward further erosion of any communal integrity. I remember experiencing this anguish first hand. I was sitting alone in the bishop’s archive in Cuzco during the early afternoon of an Andean summer day. Engrossed in reading a document concerning the commissioning of a seventeenth century painting, I barely paid attention to the noise coming up the stairs, but looked up when two men burst into the room asking for the bishop in a mixture of Quechua and Spanish. I had never met the bishop and had no idea where he was and said so. The horrible story unfolded in words of grief that the principal painting in their town’s chapel had been stolen (most surely by someone from the community itself) and they needed to report its loss to the bishop, who would surely help. The painting had protected the community, probably for centuries much like the painting I had been reading about, through its miraculous intercession and now it was gone. They had no photograph of it and could only describe in the vaguest terms what it looked like. The chances of recovery were slim and in fact it never was found. The painting had now entered another different tournament of value in which its aura shifted from that of a long venerated patron of a small out-of-the-way Andean village to being admired as an original painting of the Cuzco school as it first appears in a gallery somewhere in Lima or elsewhere.

Stories such as this are common in the Andes and elsewhere, but it is not only small communities in which art works find themselves at the heart of the community. Many modern Latin American nation states have embraced their artists, asking them to give visual articulation to the nation’s aspirations, history, and dreams. Mexico is certainly the foremost example. Diego Rivera, José Orozco, and David Siqueiros have given Mexico a rich corpus of mural and oil paintings that express its historic struggles and triumphs. Placed in public buildings, the murals also express a strong adherence to the ideological aims of the Mexican Revolution and the PRI, the Institutional Revolutionary Party.

The relationship between politics, history and aesthetics, in fact, has been a major concern throughout Latin American 20th century art, as critique, protest or affirmation. Moreover, this relationship is not only manifested in the kind of realism deployed by the Mexican muralist but in many different forms and styles as in Brazil with Andrade and the Antropofago movement, in Uruguay and Torres Garcia’s reworking of Andean Pre-Columbian motifs (Figure 4), or more recently in Colombia and Doris Salcedo with her recent haunting conceptual pieces that articulate the quotidian aspects of la Violencia.

The relationship between state and artist is not always an easy one, especially when the state commissions a work. Often the conflict elicits open public debate about the relationship between the individual and the state. I remember very well the discussion that erupted in 1988 in Quito over a mural painted by Oswaldo Guayasamín (1919-1999), Ecuador’s leading artist. Guayasamín had been commissioned to paint murals in the Palacios de Gobierno y Legislativo depicting the history of Ecuador from Pre-Columbian times to the present. Guayasamín’s painting style is heavily influenced by both the Mexican muralists and Pablo Picasso, especially Picasso’s work in the thirties. Like Picasso and Rivera, Guayasamín was closely affiliated with the Communist party. Many of Guayasamín’s paintings deal thematically with the social causes of human pain and suffering by focusing on the gestures of hands and faces to achieve a heightened expressive style (Figure 5). One can easily recall Picasso’s Guernica when looking at many of Guayasamín’s paintings. All this was openly known when he was selected to paint the murals in two government buildings. Hence it came as no surprise that his compositions for them emphasized ethnic, class, national and international struggles. One segment of the mural provoked national discussion and international displeasure. It depicted a skeletal head wearing a helmet that ominously looked a World War II German helmet with the letters CIA next to it, so that there could be no doubt as to what the image referred. Already controversial within Ecuador, this image became the center of a political firestorm when it was reported that the Secretary of State of the United States demanded its removal before he would accept an invitation to participate in the inauguration of Rodrigo Borja, Ecuador’s new president. Of course the image was meant to be offensive and few Ecuadorians, as I remember, were enthralled by it. At the same time, however, it was hard to refute the CIA’s intervention in Ecuador’s sovereignty given Philip Agee’s revelations in Inside the Company: CIA Diary published in 1975. What therefore really came to be the focus of debate was not so much the subject matter but whether the state, once it had decided to commission the artist, should act as censure over the individual expression by that artist. A Television program called Libertad de Expresión offered public debate on the issue as did editorials in the newspapers. The general feeling revolved around the issue of tolerance toward political expression, especially of oppositional views, even in public places and paid for by public monies.

Like the religious painting of the small Andean village, the Guayasamín mural became the center of the public’s attention, defining in some sense its core values. The decision was to keep the mural as it was not because everyone embraced Guayasamín’s politics, but rather the idea of free expression was represented.

Now, I am not so naíve as to suggest that some utopian moment of democracy was achieved, nor that there was not a political need demonstrate the possibility to withstand US pressure, even if it were symbolic. But what is in part interesting to me, is how central painting and sculpture in the cultural and political debates in Latin American and the roll that artists had and still have in them.

Winter/Spring 2001

Tom Cummins is an associate professor in the Department of Art History and director of the Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Chicago. He was a visiting professor in the Department of Art and Architecture, Harvard University, Fall 2000.

Related Articles

Guatemala Diary

In a deeply personal way, I feel like I am home again. Of all the places I have visited, Guatemala is the country I love and feel closest to. Certainly the most impressive aspect is the persevering Mayan people, who endured a 30-year civil war…

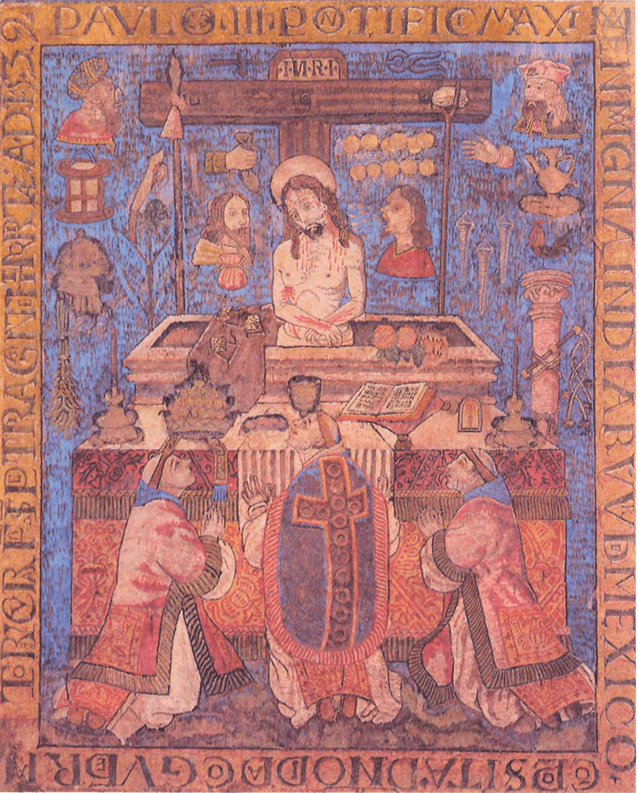

From Favela to Bairro

The Brazilian firm of Jorge Mario J¡uregui Architects is the first Latin American recipient of the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Veronica Rudge Green Award in Urban Design. The award…

Exploring New Horizons in Latin American Contemporary Art

When I first traveled to Peru by boat with my family fifty years ago, the country seemed as far away from Argentina as Boston from Buenos Aires. My husband had been sent there by W.R…