Latino Mental Health

Enhancing Services and Training

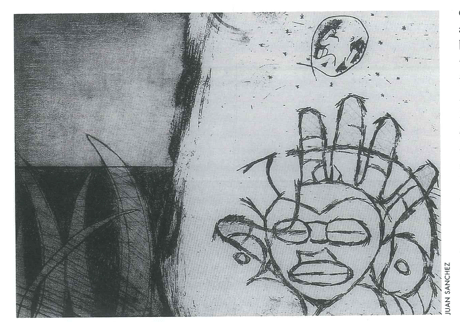

Puerto Rican artist Juan Sánchez depicts “Borinquen’s Begin- nings” (1985).

What brings you in to see me today?” This is the typical question asked of new patients during a psychiatric evaluation in a Boston clinic. When asked of a Latino patient, however, the answer does not follow a “typical” response pattern. An Anglo asked the same question may provide a linear chain of events that includes symptom type and formation, duration, and current circumstance that may be exacerbating their condition. Two parts of the doctor’s question may be less relevant to the Latino patient. Usually the patient has not come to his or her visit alone, but rather in the company of one or more family members. “You” presupposes individual identity. Latino patients sees themselves in a group context of interdependence. The word “today” presupposes that distress comes from current or recent events rather than a historical context. One Latino patient put it well when she answered: “If I told you how I got here today I would need to start by telling you why my grandmother left Honduras 45 years ago.” Thus, in this immediate exchange much is communicated about Latino identity. It is largely borne out of a family framework and historical lineage.

There is a growing need for mental health services for Latinos. In response to this need, an educational initiative has been implemented at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center’s Department of Psychiatry to offer trainees both didactic and direct clinical contact with Latino patients. It has been a pleasure to co-teach “Latino Mental Health” with Antonio Bullon, MD to a group of psychology interns, psychiatry residents and Harvard medical students.

The students learn about the difficulties Latinos face, especially those that emigrate from rural and agricultural settings. These rural immigrants struggle to acclimate to large, urban, technological societies such as those found in our major U.S. cities. Usually the migrant farmer’s skills do not transfer well to a metropolitan job market. Often times these men, heads of household, remain unemployed. Their wives become wage earners, perhaps for the first time, because their skills transfer more rapidly to jobs as nannies, cooks, and seamstresses. Family dynamics suffer, usually creating marital tension as the husband begrudgingly accepts financial dependence on his wife. The Latino man must reconcile his perceived impotence with the original intention of coming to this country to provide a “better way of life” for his family. He will often quell his despondency in alcohol or other mind-altering substances.

The next generation’s options are also tenuous. Only 52% of Latinos complete high school and less than 10% complete college. Thus these young adults are already less competitive for well paying jobs. This implies facing a life with jaded dreams and the pathogenic reality of poverty. Some 25 % of Latinos have incomes that fall below the poverty level. When basic needs are compromised, the ensuing stress can lead to significant emotional and mental unrest.

For those more fortunate Latinos coming from higher socioeconomic conditions, their transition to U.S. culture presents its own challenges. Despite their job security and greater life comforts, they feel an emotional disconnect when they experience U.S. society as frigid and mechanistic. This leaves them nostalgic for the temperate interpersonal latitudes of home. Testimonials from Latino patients convey the sentiment well. A Mexican journalist voices: “En este país no hay humanidad, uno se endureze aquí” (“In this country there is no humanity, one becomes hardened here”). The Argentine doctor attests: “Aquí hay violencia, no como en mi país, aquí hay violencia interpersonal” (Here there is violence, not like in my country, here there is interpersonal violence”).

Latinos are often at risk for depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and post-traumatic stress disorder. However, the Latino patient is often reluctant to seek out a therapist or psychiatrist fearing the stigma that comes from being labeled “loco” or crazy. Thus many Latinos suffer unnecessarily in isolation. Often times they will wait until the symptoms become more critical and debilitating, requiring a visit to the emergency room and necessitating a psychiatric hospitalization. While cultural precursors, such as stigma, make accessing help challenging, structural impediments in the mental health service sector also create road blocks on the road to receiving care. Many ambulatory settings do not have the trained staff to meet the growing demand for Latino mental health services. Deficits in psychiatric training related to working with culturally diverse patients raises serious questions about the quality of care and the need to enhance training opportunities for future providers.

In our program, the initial goal in teaching about Latino mental health has been to first familiarize trainees with important demographics related to Latinos in the United States. Trainees learn that the U.S. is the 5th largest Spanish speaking country in the world and that Latinos are the fastest growing ethnic minority group. Thereafter trainees are informed about the relevant cultural values of this community and how to make diagnoses within a cultural framework. Moving from the general to the more specific, particular emphasis is then placed on the pluralism among Latinos.

The majority culture appears to have a general bias that all Latinos are alike. Latinos often represent themselves as one homogenous group, usually with the hope of creating a critical mass and a louder political voice. The range of diversity across race, dialect, ritual, belief system, country of origin and social condition just to name a few gets overlooked.

Thus, throughout the course trainees are provided with real clinical vignettes and live interviews with patients to highlight the texture of the Latino experience. They learn firsthand about the Dominican woman working three jobs to raise money to bring her children to the U.S., whose plans are indefinitely postponed when she becomes medically disabled and severely depressed; the Venezuelan graduate student whose attempts at academic success and acculturation leave her overwhelmed and prone to bulimia; the Puerto Rican father of five, who is laid off after 25 years in a factory job, but cannot find work given his illiteracy and suffers a psychotic break; the gay, HIV-positive undocumented Costa-Rican man with a severe anxiety disorder and hypervigilant that the INS will deport him; the upper-class banker from Chile with a crippling social phobia; the young man from rural El Salvador who is sure that his friend hexed him with “Mal De Ojo”/Evil Eye leaving him listless and feeling possessed.

The course also focuses on the potential clash between Latino culture and the culture of the medical center or department practice. The fact that the hospital has a culture and identity of its own, worthy of scrutiny, often appears to be a novel idea to course attendees. For instance, strict boundaries and confidential information in U.S. medical practice and psychiatry in particular arises from Western philosophy and legal concerns for the individual’s right to privacy. This concern for privacy can appear very foreign to the Latino patient. The focus on the individual during a psychiatric evaluation and the seeming impenetrable boundaries between the patient’s disclosures and the patient’s loved ones feels awkward to the Latino patient where the expectation for family involvement and validation about any health procedure is seen as a standard of care. Trainees are instructed on how to wed both worlds: that of the profession’s cultural dictates and the patient’s cultural framework.

In a related topic trainees are also alerted to the process of “personalismo” in which Latinos put a premium on interpersonal contacts. The Latino patient makes a strong bond with his or her provider whereby trust and loyalty to the clinician evolve over time; the provider is considered a valuable member of the patient’s family. Allegiance to the affiliated institution is only secondary.

Training hospitals in the United States have a culture of rotating interns and residents through different specialties in order to maximize clinical exposure. Such a custom, however, disrupts the expectation that the same clinician will continuously provide care to the same patient. If the Latino patient is not made aware of this hospital practice, a change in provider may be viewed as evidence that the hospital does not take their care seriously’a default reasoning borne out of past vulnerabilities from prejudicial exchanges. Thus trainees are instructed to explain hospital policies from the onset to minimize potential misunderstandings with their Latino patients.

Towards the end of the course participants are well versed in the knowledge that individuals, groups, and institutions all have cultural identities with rules of protocol and expectation. Hopefully with this knowledge comes a new appreciation for the demands of living and practicing in a culturally pluralistic society. That is, we must constantly introduce ourselves to each other defining our goal and purpose, be humbled by our naiveté of the other, and eager to find common ground.

Fall 2000

Rebeca Chamorro is a clinical psychologist and Director of the Latino Mental Health Service at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, a Harvard teaching hospital. She is an instructor of psychology at Harvard Medical School and the recipient of several grants that promote diversity training in mental health and direct service to the Latino community.

Related Articles

Health: the Hope of Haiti

At no time have I felt more vital than in serving at Partners In Health (PIH), and seldom more needed than in places like Haiti. In the Haitian people, as well as in every other country that PIH serves, we find an…

Whither Equity in Health?

A waiting room in a charity clinic in rural Haiti. It is a humid afternoon, and huge drops of warm rain are starting to fall. A young woman is watching as her ten-year-old son, Dominique, clutches…

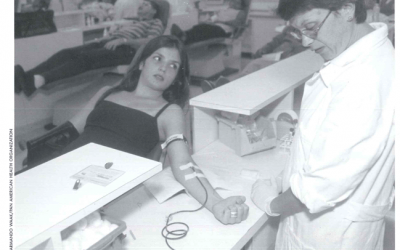

Safe Blood for Transfusion

José Oscar Cotto López has donated 140 pints of blood since 1966. The 53-year old resident of San Salvador, El Salvador, does so because he believes it is an expression of love. “We must be…