Latin@s in School

The Most Segregated … Soon the Largest Minority

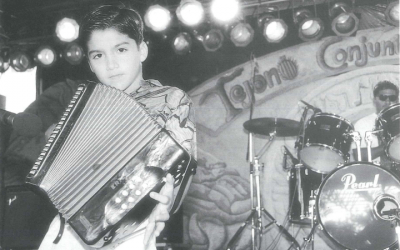

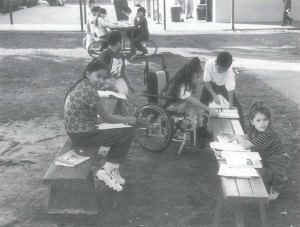

Children take a break in a Riverside school, California. Photo by Nathalia Jaramilo.

At the beginning of this new century, we have become a far more racially and ethnically mixed nation, but in our schools, the color lines of racial and ethnic separation are tightening. Latin@ students, rapidly becoming our largest minority group but have been even more segregated than African Americans for years. The trends are toward severe racial and ethnic separation in schools that are deeply unequal.

We already have five states where the majority of all public school students are from “minority” backgrounds and these include our two largest and most influential states, California and Texas, which have produced four of the last six candidates elected President. In California, the Latin@ student body already slightly exceeds the white total in a state where one in nine students is of Asian origin, and one in eleven is black. The state has many schools where the integration is primarily between Latin@s and Asians.

We find a rapid ongoing change in the racial composition of American schools and the emergence of many schools with three or more racial groups. Latin@. All racial groups except whites experience considerable diversity in their schools. However, whites remain in overwhelmingly white schools even in regions with very large majorities of non-white enrollments. Latinos and Blacks are located in schools strongly dominated by Latino and Black students, the two major groups with the lowest test scores.

Though we usually think of segregation in racial and ethnic terms, it’s important to also realize that the spreading segregation has a strong class component. Latin@ and African American students segregated into predominantly non-white schools are very likely to find themselves in schools with a concentration of poverty. Schools that are more than nine-tenths Latino and/or African American are 11 times more likely than white schools to face concentrated poverty. Majority white schools, on the other hand, almost always enroll high proportions of students from the middle class. This is the root of a great deal of confusion about the segregation issue since many of the harms of segregation arise not from race itself but from the concentrated poverty that is so strongly linked to race and many of the advantages of desegregation relate to strengths of successful middle class schools.

Concentrated poverty is powerfully linked to lower educational achievement. Schools with children at the poverty level face serious challenges, such as lower parent education levels, less availability of advanced courses, teachers without credentials in the subject they are teaching, instability of enrollment, dropouts, untreated health problems and lower college-going rates, and negative peer group pressures. The nation’s large program of compensatory education, Title I, has had great difficulty achieving gains in schools with highly concentrated poverty. Students receiving Title I aid in high poverty schools do worse than similarly poor students in less impoverished schools receiving no money. When school districts return to neighborhood schools, white students tend to sit next to middle class students but Latin@ and black students are likely to be next to impoverished students. Since Latinos have the largest and the youngest families, their neighborhood schools are also much more likely to be seriously overcrowded.

Debates over the exact academic impact of desegregation continue. However, there’s no question that Latin@ and black students in racially integrated schools are generally in schools with higher levels of average academic achievement than are their counterparts in segregated schools. Desegregation does not assure that students will receive the better opportunities in those schools–that depends on how the interracial school is run–but it does usually put minority students in schools which have better opportunities and better prepared peer groups and better connections with colleges.

With the imposition of mandatory state tests for high school graduation, harmful consequences for students attending less competitive schools are steadily increasing. Chances for college also decrease as college admissions standards are rising and college remedial classes are cut. In addition, affirmative action has already been abolished in our two largest states, both of which will soon have majorities of Latino students. These two states, California and Texas, educate about three of every five U.S. Latino students.

We are clearly in a period when many policymakers, courts, and opinion makers assume that desegregation is no longer necessary. Polls show that most white Americans believe that equal educational opportunity is being provided. National political leaders have largely ignored the growth of segregation by race and income in the 1990s. Thus, knowledge of trends in segregation and its closely related inequalities are even more crucial now. For example, increased testing requirements for high school graduation, for passing from one grade to the next, and college entrance can only be fair if we offer equal preparation to children, regardless of skin color and language. Increasing segregation, however, pushes us in the opposite direction because it creates more unequal schools, particularly for low income minority children, who most frequently receive low test scores. White and Asian students are much more likely to be in schools where the competition is much stronger, the teachers are teaching in their own field.

The issue has not even figured among the Clinton administration’s priorities for education policy, despite the fact that the Clinton administration has seen the largest increases in segregation in the last half century. The Supreme Court, which opened the possibility of desegregated education in the 1950s has taken decisive steps to end desegregation plans in the 1990s and some lower courts are prohibiting even voluntary local plans. The Reagan and Bush Administrations stacked the courts with conservative judges opposed to minority rights and civil rights have been limited in areas ranging from voting to employment to schools to college admissions. Conservatives in California have succeeded in outlawing affirmative action and crippling bilingual education through referenda. The school desegregation rollback is part of a much larger reversal that is threatening the future of Latinos.

A series of 1990s Supreme Court decisions helped push the country away from the civil rights ideal of integrated schools where all students got equal opportunity toward the old idea of “separate but equal,” articulated in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision. Separate but equal was overturned six decades later by Brown’s declaration that separate schools were inherently unequal. During the next thirty years, the law developed in a series of decisions to require immediate and complete desegregation of blacks in states with a history of official discrimination, even when busing was required to overcome residential segregation. The decisive breakthrough against segregation of blacks came during the Johnson Administration when the President actively enforced the law and made the south the nation’s most integrated region. During this period there was a sharp drop in the black-white test score gap in the South.

When the modern school desegregation battles took shape in the 1950s, the challenge was to open up a white school system to the one-tenth of students who were black; Latin@ students received very little attention nationally. In 1973, the Supreme Court in a case from Denver, Keyes, extended desegregation requirements to Northern and Western cities and recognized the right of Latin@ as well as African American students to desegregated education. The Nixon Administration, however, refused to implement the law in the nation’s cities and its civil rights office proposed bilingual education rather than desegregation. The Reagan administration, however, fought desegregation and also assailed bilingual education, in part because of claims that it was separatist. The administration rapidly dropped Justice Department efforts to open up suburban schools for Latinos segregated in Phoenix and Houston and supported the California proposition that led to the end of Los Angeles desegregation.

A series of decisions by a Supreme Court reconstructed by the appointees of Presidents Reagan and Bush triggered piecemeal dismantling of desegregation plan where they had been attained. This particularly affects Latin@s, whose presence in the public school systems has tripled since the civil rights era. Since 1968, the enrollment of Hispanics has increased by 218% while African Americans have grown more than a fifth and the white enrollment is down by a sixth. In the l996-97 school year, Latin@ enrollment accounted for 14%.

The school segregation statistics show that the next generation of Latin@s are experiencing significantly less contact with non-Latin@ whites. 45% of Latin@s were in majority white schools in 1968 but only 25% in 1996.

Latin@ segregation has been increasing ever since data was first collected in the 1960s but the issue has never received much attention since the great increase came after the civil rights era. There never was a significant effort to enforce Keyes, and substantial desegregation for Latin@s occurred in only a few places. Segregation has been rapidly growing in the states where they have the largest enrollments. The Northeast, where New York is the most segregated state in the nation, continues to be the most segregated region but the South and the West are just behind. The West, now has 77% of Latin@ children in predominantly minority schools. A very substantial share of Latin@s are now attending intensely segregated (90-100% non-white) schools-46% in the Northeast, 38% in the South, and 33% in the West, where this level of segregation was uncommon two decades ago.

The only state with a high level of Latin@ enrollment that did not show severe segregation in 1996 was Colorado. The Denver case was the one in which the right of Latin@s to desegregated education was recognized by the Supreme Court. In 1997, however, the Federal District Court approved permitting Denver to return to segregated neighborhood schools. That was done.

Those examining the increase in Latin@ segregation may well ask whether or not it is simply a reflection of the rising share of Latin@s in the school age population and the declining share of whites. The answer to this question is yes, a large share of the increase is demographic and full desegregation in majority white schools is no longer a possibility in some states. (Although there would also be advantages for Latino students in getting access to schools with many Asian students.) A new analysis for the U.S. National Center for Education Statistics shows that much of the decline in desegregation with whites could be accounted for by the growth of the Latin@ enrollment between 1987 and 1996, since there were few major desegregation plans to dismantle in the West. However, whites remain highly segregated in the regions of rapid Latin@ enrollment growth.

The public schools of the U.S. foreshadow the dramatic transformation of American society that will occur in the next generation. We are a society in which the school age population is much more diverse than the older population. The social reality in our schools is far removed from the reality in our politics, since voters are older and much more likely to be white.

Latin@s and blacks in the central cities of large metropolitan areas were by far the most segregated. More than a fifth of Latino students attended school in the ten largest city districts compared to less than 2% of whites.

But the suburbs are also changing. In a society which is now dominated by the suburbs, it is extremely interesting that 30% of Latin@s and 20% of blacks are now enrolled in the suburban schools of large metropolitan areas, and another 6% attend school in the suburbs of smaller metropolitan areas, but serious segregation is emerging within these communities, particularly in the nation’s large metropolitan areas. Since trends suggest that we will face a vast increase in suburban diversity, this raises challenges for thousands of communities. The outcome will help determine whether or not the rising Latino middle class receives the access and opportunities accorded to earlier immigrant communities or faces isolation as do middle class blacks.

The population growth of minority students is going to be overwhelmingly suburban if the existing trends continue. One of the most important questions for the next generation will be whether or not the suburbs will repeat the experience of the central cities or learn how to operate stable integrated schools.

We are floating back toward an educational pattern that has never in the nation’s history produced equal and successful schools. There is no good evidence that it will work now. The 1990’s have actually seen the once shrinking racial achievement gaps begin to widen again on some tests. It is clear, then, that the Administration’s favored educational policies in place are not likely to produce equal segregated schools. The schools need many other things besides integration, but ethnic, linguistic, and economic isolation compound those problems. Reversing the trends of intensifying segregation and inequality will be difficult, but the costs of passively accepting them are likely to be immense.

Gary Orfield, a professor of Education and Social Policy at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, also holds an appointment at the Kennedy School of Government. He is co-director of the Civil Rights Project at Harvard University with a special interest in the study of civil rights, education, urban policy, and minority opportunity. He is the co-author of the 1999 report, Resegregation in American Schools, and the 1969 book, Dismantling Desegregation (New Press, New York, 1996).

Related Articles

Forum on U.S. Hispanics in Madrid

The Trans-Atlantic Project, an academic initiative to study the cultural interactions between Europe, the U.S. and Latin America has been invited by Casa de América, Madrid, to present a …

Cuba Study Tour

Waiting at José Marti International Airport for the first Harvard students to arrive for January’s DRCLAS Cuba Study Tour, my companion, a theater critic at Casa de las Américas, commented to me …

The Soulfulness of Black and Brown Folk

And so, by faithful chance, the negro folksong – the rhythmic cry of the slave – stands to-day not simply as the sole American music, but as the most beautiful expression of human experience …