A Review of Laws of Chance: Brazil’s Clandestine Lottery and the Making of Urban Public Life

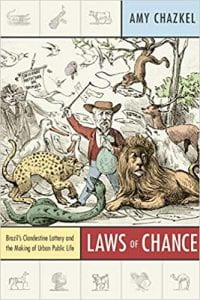

Laws of Chance: Brazil’s Clandestine Lottery and the Making of Urban Public Life, by Amy Chazkel Durham: Duke University Press, 2011, 356 pp.

Anyone who has visited Rio de Janeiro for more than a few weeks inevitably hears about the jogo do bicho, an illegal gambling activity that has been roughly translated into English as the animal game. One might notice a man or woman permanently stationed at the same location next to an apartment building or at a newsstand. Throughout the day, hundreds of people will approach him or her, quickly engage in a short conversation, pass on some small bills, and exchange a slip of paper. A bet has been placed in an underworld of petty commercial exchanges known as the jogo do bicho. It is regulated by the reputation of the person on the street corner and the trust in her or him by the client who risks some cash for a chance to multiply a small wager into a sum that might pay off bills or even allow for an extravagant purchase.

This clandestine game of chance, in which sets of numbers are linked to twenty-five animals and the outcome of a bet follows the winning numbers of the official national lottery, constitutes a century-old tradition in Brazil’s former capital. How did a simple lottery devised at the turn of the twentieth century by a real estate entrepreneur to encourage residents of Rio de Janeiro to visit a zoo in the outskirts of the city become a ubiquitous underground game of chance widely played by both the popular and middle classes? Why did the state quickly outlaw this numbers game? In what ways did it criminalize informal popular practices, such as small-time gambling, a part of the development of modern, urban public life in the aftermath of slavery’s abolition in 1888 and the establishment of a republican regime fourteen months later? How can historians explain the fact that the police spent considerable time policing the practice in the first decades of the 20th century, when the game of chance assumed such widespread popularity, yet so few people were convicted of engaging in this illicit pastime even when the organizers of the jogo do bicho were caught red-handed with proof that they were receiving bets? To what extent is the jogo do bicho an early example of the informal economy that has expanded so significantly in twentieth-century Brazil?

In this theoretically rich and meticulously researched work, Chazkal examines Brazil’s most famous game of chance as a means of understanding the complexities of public sociability and its relationship to everyday forms of petty economic exchanges. She argues that a form of enclosure operated in urban Brazil in the late 19th century, as consumer capitalism took hold and the state privatized many forms of public life. Freed slaves, urban poor, and recent immigrants to Rio de Janeiro all faced a rising cost of living and were surrounded by new social controls. Earning a living as a petty street vendor or part-time laborer was one of the numerous livelihoods that the lower classes engaged in as a means of surviving in the nation’s capital. Yet, the new republican regime closely regulated the right to occupy the streets, participate in minor commerce, or even live in the city’s center. The jogo do bicho, which offered those of modest means a chance to improve their lot, was one of the dozens of economic transactions that circulated small amounts of money among the poor beyond the purview of the law. Restrictions on this illicit form of betting served as yet another means of affirming the state’s right to control the quotidian activities of its citizens at a moment of intense urbanization and modernization.

For a historian to document the social history of an illegal activity is no easy task, as those engaged in the pursuit are unlikely to leave much evidence that authorities (to say nothing of modern-day scholars) might uncover that could link them to an outlawed transaction. Moreover, documentation about bribes to authorities to avoid harassment of those participating in banned activities is rarely found in state archives. Historians do have some leads to follow, and Chazkel diligently has pursued all of them. Arrest records, evidence retained in investigations, and the statements made after official interrogations reveal an interaction between the police and the persecuted that constituted a cat-and-mouse dynamic of insistent accusations of crime violations and evasions of prosecution through at times far-fetched denials of any participation in the game. As this work carefully documents, prosecutors and police made great efforts in their attempts to control this form of gambling, yet failed to get many convictions, even when authorities captured people with wads of money and notations that clearly indicated their involvement in the practice. Chazkel persuasively shows that although officials at all levels might have been involved in receiving betting kickbacks in exchange for protecting those organizing the underground game, many also actively participated in repressing this popular form of gambling entertainment. After all, an officer of the law could not expect to receive protection money if there were no threat that the police might arrest a lawbreaker. So the jogo was both repressed and permitted. Yet, the court system was quite lenient in sentencing those held under suspicion of running the game, with a conviction rate as low as four percent of those arrested. The heavy hand of the law was so harsh in its pursuit of violators that many judicial officials sided with defendants even when circumstantial evidence pointed to their involvement. Chazkel argues that the tension between agents of the state tasked with repressing this form of gambling and those responsible for deciding the guilt or innocence of those arrested reflected the consolidation of a judicial system based on arbitrary and informal implementation of the law both on the street and in the courthouse.

Chazkel draws on a wide array of theoretical models to help contextualize the lasting importance of the jogo as it became embedded in popular culture. In additional to its varied social meanings, the game was a surprisingly successful and stable economic enterprise. Those making a wager could count on the fact that the bet taker’s word was trustworthy and the person placing some money on a given number/animal would get paid should her or his luck play out. As the author poignantly points out, in a world in which so many aspects of everyday life were unpredictable, the jogo remained a secure and reliable undertaking. Chazkel convincingly lays out how, rather than symbolizing a remnant of a pre-modern folk tradition, a fetishized popular practice, or an irrational economic endeavor, the game of chance reflected modernizing trends among the poor and working classes, who became integrated into the money economy and circulated freely in the interstices of urban Brazil under the watchful gaze of representatives of the state that alternately turned an eye, collected a bribe, or carried out an arrest.

This unique optic on early twentieth-century Brazil is beautifully written and originally argued. Surprisingly, it is the first comprehensive and meticulous study of the animal game in Portuguese or in English. It stands as an important contribution to understanding modern Brazilian history and culture.

James N. Green is a Professor of History and Brazilian Studies at Brown University. His books include We Cannot Remain Silent: Opposition to the Brazilian Military Dictatorship in the United States (Duke, 2010) and Beyond Carnival: Male Homosexuality in Twentieth-century Brazil (University of Chicago, 1999). He is currently working on a biography of Herbert Daniel, a Brazilian guerrilla leader, political exile, and AIDS activist.

Related Articles

Mexico’s Challenges

When Felipe Calderón took oath as Mexico’s president, he identified security policy—particularly a struggle against criminal organizations—as the flagship policy of his administration. Like…

Organized and Disorganized Crime

In some countries of the Caribbean, crime has taken on a new face. It is true that criminal violence can hardly be considered a new phenomenon in the region. Puerto Rico and Jamaica…

After the UPPs

Growing up in Copacabana, Rio de Janeiro, I was constantly aware of serious public safety problems. That probably played a big role in my choice of profession and specialization. Rio is a…