Life in a Venezuelan Oil Camp

Tío Conejo Meets Uncle Sam

I grew up in a Venezuelan oil camp. Ever since I can remember, I have heard both Spanish and English spoken all around me or conveyed through music or films. With my family, I ate traditional Venezuelan arepas, cachapas, carne mechada (shredded beef), fried plantain, and black beans, but invitations to dinners at friends’ houses often meant sampling curry goat, roti and thali,borscht, or U.S.- style barbecues.

In many ways, Caripito, the oil town where I was raised, embodied the changes occurring throughout Venezuela after the discovery of oil. In 1930, the Standard Oil Company of Venezuela built a port facility and began work on a refinery in this town, in the state of Monagas in eastern Venezuela, to process oil from fields in Quiriquire, Jusepin and Temblador. The promise of the oil attracted Venezuelans from throughout the country; many caripiteños (people of Caripito) had roots in the adjacent state of Sucre. In succeeding decades, people from Trinidad, Italy, Lebanon and even a handful of Russian exiles also made their way to Caripito. By 1939, Caripito had a population estimated at about 5,000 people, some 300 of whom were “white Americans.” In Caripito, as in most oil camps, to be white increasingly became synonymous with being a U.S. expatriate. By 1960, the total population had soared to a little over 20,000 people.

At an early age I became acutely aware of how different the oil camp experience was from the rest of Venezuela. After several years of living in the residential enclave, and seeking to avoid the demanding social expectations of the camp, my parents moved to Los Mangos, a neighborhood of Caripito. However, they also recognized the importance of straddling both worlds, and my mother dutifully drove me everyday to the company school and our family selectively participated in many camp activities.

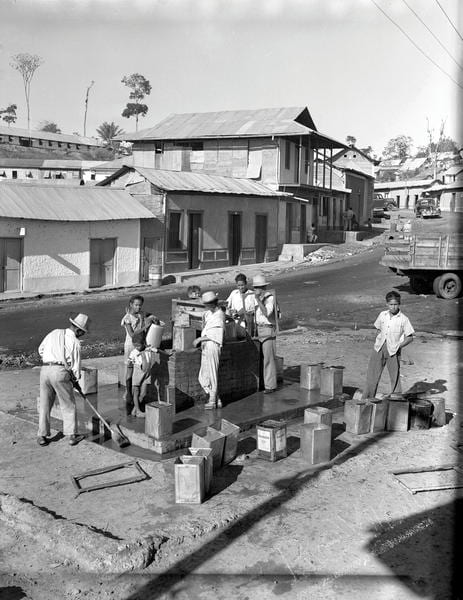

After oil was discovered in 1914, Venezuelan production was concentrated in the interior of the country, where infrastructure and sanitary conditions had improved little since the 19th century. To ensure operations, foreign companies took charge of basic services including electricity, water, sewage, roads, housing, health services, schooling and a commissary. In these rural areas, the companies supplanted the state, and local communities became dependent on foreign enterprises for basic services.

Standard Oil Company of Venezuela (later Creole Petroleum, a subsidiary of Standard Oil Company of New Jersey), and Shell Oil built residential camps to house their employees. In classic Jim Crow fashion, the companies created distinct areas for foreigners, typically white U.S. employees or “senior staff,” Venezuelan professionals or “junior” staff, and more modest housing for workers. The senior staff clubs included a pool, golf course, tennis and basketball courts, as well as bowling alleys while the workers club typically had a baseball field, a bolas criollas court (bocce), a bar and a dance floor. In spite of this hierarchy, by the 1950s the camps became symbols of U.S.-sponsored “modernity,” with orderly communities, higher salaries and access to a full range of services that sharply contrasted with conditions found in the local Venezuelan settlements.

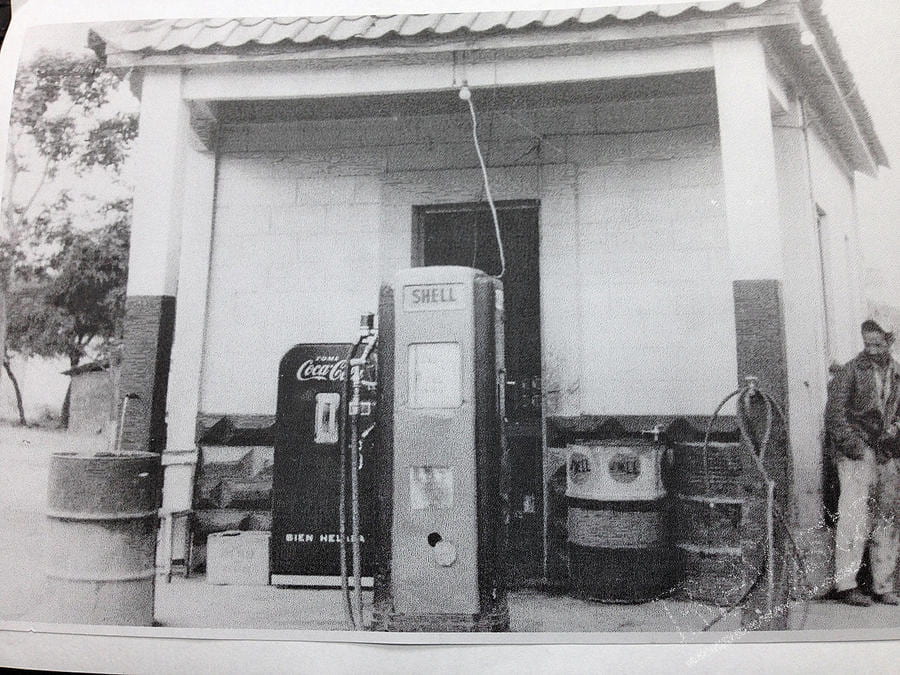

A Coca Cola machine at a Shell gas station reflects the prevailing “American way of life.” Photo courtesy of Miguel Tinker Salas.

The camps represented an improvised and largely transitory society made up of residents from different parts of the United States and Venezuela. The camps allowed Venezuelans to interact with people from other regions, races and countries. With few if any roots to the local community, workers were frequently transferred between camps, and the company promoted an esprit de corps among its employees that centered on an all-encompassing corporate culture. Company practices favored hiring family members, thus handing down values such as the “American way of life” from generation to generation.

Yet despite their artificial nature, the camps left an enduring legacy in Venezuelan culture and society. For the generations that worked in the oil industry, the camps reinforced their image as a privileged sector of Venezuelan society. Just as importantly, the camps were sites of cultural and social exchange, with the “American way of life” influencing everything from politics to values. Those employed in the industry expected the Venezuelan state to be the guardian of this distinctive lifestyle. Many residents retained a collective nostalgia for the experience of the camps, overlooking the racial and social hierarchy that prevailed and the detachment that existed from Venezuelan society.

Caripito was typical of this oil town culture. The same ships that navigated the San Juan River to load oil also brought an array of U.S. fruits and canned products for sale in the camp commissary. I still recall the amazement of eating individually wrapped red Washington apples for the first time, or savoring crisp Mexican tortillas that came in vacuum-sealed metal cans. Long before McDonalds appeared in Venezuela, the soda fountain at the company club regularly served the “all American meal” consisting of hamburgers, fries, and Coke. The Venezuelan diet quickly incorporated U.S. culinary preferences and tastes.

Like other children in the camps, I went to a bilingual company school that incorporated both the Venezuelan and U.S.-mandated curriculum. To a certain extent, exposure to a bicultural milieu shaped the consciousness and personal sensibilities of people like myself who inhabited the camps or its environs. Beyond simply the ability to speak both languages, the camps conveyed the importance of dealing with difference. This experience, however, was not shared equally, and it usually fell on the Venezuelans to learn English. Besides understanding English, familiarity with U.S. norms and customs proved essential for Venezuelans seeking to advance in the company. Interacting with foreigners became natural, but so did the imposition of a social racial hierarchy reinforced by U.S. expatriates at the top of the social order.

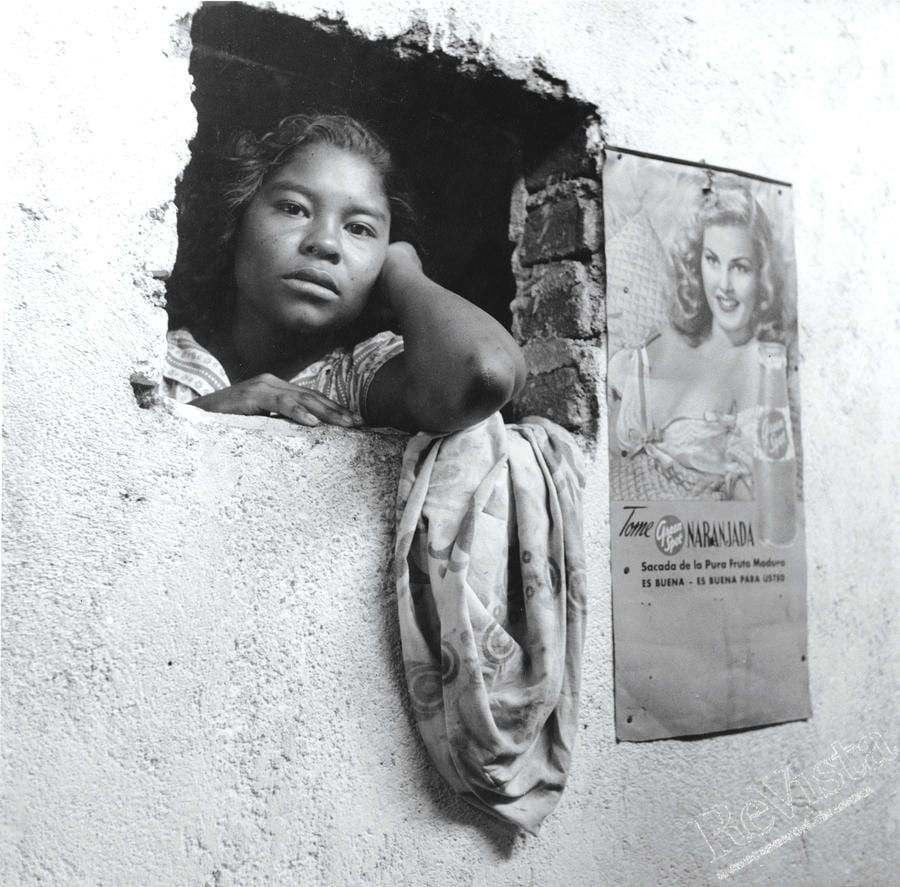

A young Venezuelan woman looks pensively out of her humble abode, which is posted with an ad for orange soda. Photo courtesy of the University of Louisville, Stryker Collection Special Archive.

Festivities in oil camps highlighted the extent to which the camps represented self-contained enclaves of U.S. culture in the heart of Venezuela. Seldom if ever questioned, the pervasive influence of the U.S. oil industry made political and cultural ties with the north appear normal. Celebrations of the 4th of July melded with Venezuelan independence on the 5th of July, becoming shared events that allowed politicians and company officials to make largely perfunctory claims of solidarity. Expatriates, especially from Texas, saw the occasion as an opportunity to prepare Southwest-style barbecues where local beer flowed freely. Uncle Sam, the benevolent father figure that later morphed into a symbol of U.S. imperialism, mixed freely with Tío Conejo, a shrewd rabbit from a Venezuelan folk tale who regularly outwits his tiger nemesis, Tío Tigre.

Other festivities, however, diverged from Venezuelan traditions for which no parallel activity existed. During Halloween, children dressed as Mickey Mouse, cowboys, ghosts and witches wandered throughout the senior camp asking for candy from befuddled Venezuelans. Thanksgiving celebrations by the U.S. expatriate community, which often included public gatherings, and the consumption of frozen turkeys imported from the United States, remained an exclusively foreign activity. Venezuelans outside of the oil industry had no connection to these events. A traditional Christmas in Venezuela had always included building a Nativity scene, but in the oil camps, this practice was slowly displaced by ornament-laden imported pine trees. To add to the festive mood, the oil company typically decorated a nearby oil well or water tower with colored lights in the shape of a Christmas tree, with adjacent loudspeakers playing seasonal melodies.

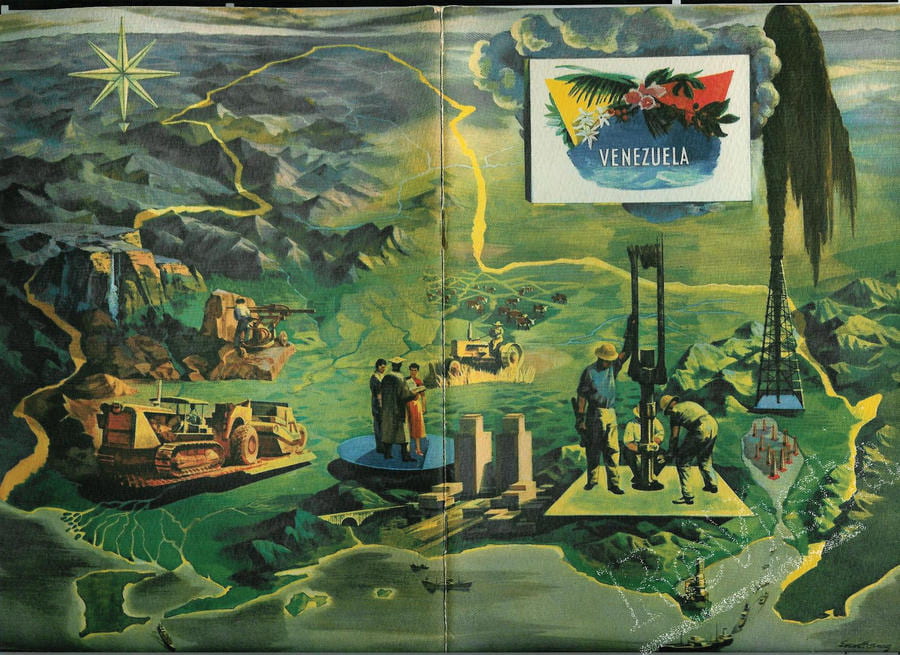

A colorful road map produced by Citibank Venezuela in the 1950s. Photo courtesy of Miguel Tinker Salas.

Shortwave radios allowed expatriates—and some oil camp Venezuelans—to keep track of events in the United States and important news quickly spread. This was long before the Internet or cable television made speedy news a fact of life. I can recall seeing my U.S. teacher at the Cristóbal Mendoza grammar school break down in tears when the school loudspeaker announced the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Another way of connecting to U.S. culture was through movies shown at the camp club; Spanish subtitles allowed the Venezuelan audience to follow the action without paying second thought to the overt racism present in many of the U.S. Westerns that stereotyped Mexicans and Native Americans. Many of my U.S. classmates at the camp shared LP records that came with a coonskin cap, plastic musket, and powder horn and recounted the exploits of Davy Crocket starring Fess Parker.

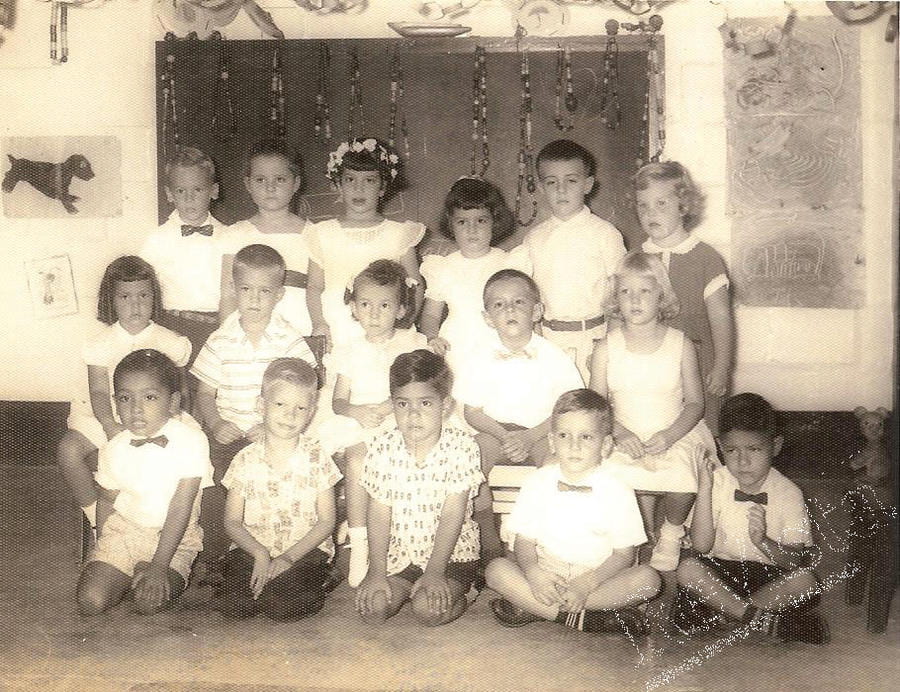

The author of this article is sitting on the floor, second from the right, wearing a bow tie and white shirt. Photo courtesy of Miguel Tinker Salas.

Venezuelans who did not live in the camp or work in oil sought entertainment in the San Luis movie house in La Sabana across from the Creole Petroleum refinery. I straddled both worlds, and loved to watch Mexican cowboy (charros) films or the comedy of Cantinflas and Tin Tan in the old-fashioned movie house that featured a range of seating from common wooden benches to higher-priced chairs. Outside the theater, my friends and I looked forward to savoring corn empanadas de cazón (dried shark), a local favorite in eastern Venezuela, made by an Afro-Venezuelan woman.

The importance of oil to the U.S. economy and military thrust Venezuela into the midst of the Cold War. In 1962, Peace Corp volunteers were assigned to Caripito to teach English in secondary schools and promote U.S. values. In case their efforts failed, Green Beret advisors gathered intelligence and trained the Venezuelan National Guard. In 1962, guerrillas launched an offensive in eastern Venezuela. The U.S. military advisors assigned to Caripito asked my local Scout troop to report on “suspicious activity,” including spent cartridges we might find as we hiked through the rainforest. To assuage discontent, the town’s poor also received sacks of grain from the Alliance for Progress and from Caritas, a Catholic charity. As I accompanied my parents into some of the poorest neighborhoods of Caripito to distribute food packages it became evident that oil had not benefited all sectors of society equally. The camps highlighted the existence of two Venezuelas, one benefiting from oil, and one for which the promise of oil remained elusive.

The washing machine is emblematic of the type of modern purchase made possible by the booming Venezuelan oil industry. Photo courtesy of the University of Louisville, Stryker Collection Special Archive.

Oil never fully transformed Venezuela, but rather it created the illusion of modernity in a country where high levels of inequality persisted. The camps became a tangible symbol of this disparity. Local residents resented the inequities in lifestyle; businesses complained about closed markets; the government worried about divided loyalties; and the left viewed them as part of U.S. exploitation of Venezuela’s labor and resources. During the 1970s, popular protest singer Ali Primera wrote Perdóname Tío Juan (Forgive me Uncle John):

Having successfully created a trained and acculturated labor force imbued with company values, even the oil companies believed the camps had outlived their usefulness. Despite their eventual integration into local communities, the lived experiences of those employed in the industry coalesced with the perspectives of mid dle- and upper-classes that viewed oil as the guarantor of their status. Attempts to recapture the illusory sense of modernity experienced during this period inform many of the political divisions that characterize contemporary Venezuela.

Es que usted no se ha paseado

por un campo petrolero/ usted no ve que se llevan

lo que es de nuestra tierra/

y sólo nos van dejando

miseria y sudor de obrero/

y sólo nos van dejando/

miseria y sudor de obrero.

(You have not visited an oil camp, you do not see that they take what belongs to our land, and all they leave us is misery and the sweat of our worker’s and all they leave us is misery and the sweat of workers.)

Fall 2015, Volume XV, Number 1

Miguel Tinker Salas is Professor of Latin American History and Chicano/a Latino/a Studies at Pomona College in Claremont, California. He is the author of Venezuela, What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2015) and The Enduring Legacy: Oil, Culture and Society in Venezuela (Duke University Press, 2009), among other books.

Related Articles

Oil and Indigenous Communities

On a drizzly morning in late February, a boat full of silent Kukama men motored slowly into the flooded forest off the Marañón River in northern Peru. Cutting the…

Mexico’s Energy Reform

The small, white-washed classroom at the University in Minatitlán, Veracruz, was packed with a couple dozen people who, although neighbors, had never met…

Geothermal Energy in Central America

When we think about global technology leaders, Central America does not typically come to mind. But Central American countries have indeed been in the…