Life through Medications

Dementia Care in Brazil

Photos courtesy of Annette Leibing

It is another morning at the geriatric outpatient clinic of the local university hospital. I accompany one of the residents who guides an old woman in a wheelchair and three of her seven adult children into the examination room. The room is so small that there’s only space for a writing desk with three chairs and an examination couch. The resident starts asking one of the daughters about her mother’s medications—an endless stream of questions that illustrates the way the older woman is being acknowledged as the outcome of an abstract and complicated management of symptoms and biochemical agents.

Dr. C.: How much are you giving?

Daughter: As you wrote it down: at 4 pm give one [pill].

Dr. C.: Of 25 [mg].

Daughter: Of 25; and at night one of 100, around 9 pm and…

Dr. C. (surprised): Ah, you are giving a whole of 100 or…?

Daughter: Yes, a whole one. With that she sleeps all night.

Dr. C.: Who is giving the medications? She lives with your family?

Daughter: No, we live in the same building; she lives with G. [the son who is sitting beside me]. He recently went to the Public Defender, but it is so complicated…

The daughter explains that G. is trying to get his mother’s custody, so that he can have access to her bank account with her small pension, but one of his brothers is trying to impede that.

Dr. C.: So you are having difficulty with buying the meds?

Daughter: Not really, because I insist that each sibling pays a part. I insist!

The conversation continues with a discussion about the elderly woman’s bowel movements, the safety of the bathroom, and how to avoid falls. The daughter tells us the horror she felt when she found her mother playing with her excrement, her hands and hair full with feces. “She who was always so vain!”

Dr. C.: So, her feces are solid, right? You give Quetiapina 25 in the afternoon, and 100 at night and Citalopram 20 mg, right?

Daughter: Right.

Dr. C.: And the Selozoc.

Daughter: That’s the one for the heart, right?

Dr. C.: It’s the Metropolol.

Daughter: That’s it.

Daughter: Last Friday you gave us the prescription so I can get it at the posto [public outpatient clinic]. (…) I couldn’t get it – the only med I got at the posto [for free] was the AAS.

Dr. C.: And then I wrote [she looks into her notes] I changed the Amiloride with Hidrocloro, (…), right?

Daughter: Yes, that’s it.

Dr. C.: And the Rozucor I changed for the Sinavastatina, you have to pay for it.

(…)

Dr. C.: But The Metropolol you get at the posto.

Daughter: The ‘Metro’ I bought… They didn’t have it at the posto, so I bought it.

Dr. C.: But the AAS, the Hidrocloro.

Daughter: The Hidrocloro is for the stomach, right?

Dr. C.: The Hidrocloro is a diuretic, before it was the Moduretic. (…) That’s because the Moduretic was a combination of amiloride with hidrocloro, so I changed it, because now she is only using the Hidrocloro.

The resident turns to me and explains that the diagnosis is a probable Alzheimer’s disease—probable because of the many other diseases, comorbidities. It is “the cowardly disease,” says the daughter, because “she was so vain, so beautiful, always so very well dressed, nails, pedicure – even at home. And now this.”

The son G., who was sitting beside me, speaks for the first time.

Son G.: She is sleeping all the time.

Dr. C.: That was after we readjusted the medications?

Son G.: Yes. There are days she lays down, doesn’t even take the meds at night, so I try… ahm…But when she is a little more awake, I put a little bit of perfume on her, so she feels good about herself.

The old woman: screams [and says something unintelligible.

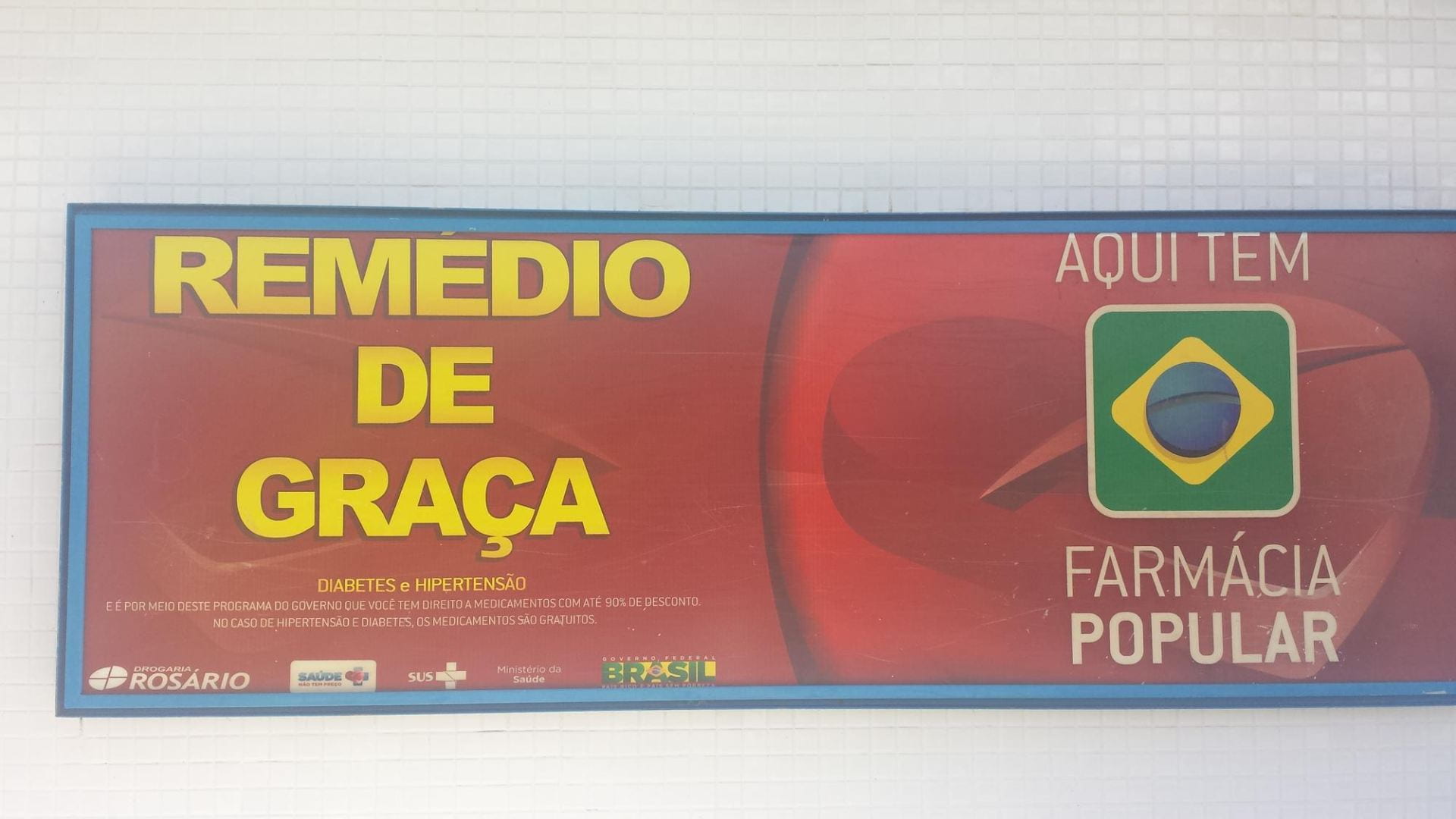

As in the case of this elderly woman and her relatives, growing old in Brazil cannot be understood without taking into consideration the important role medications play in clinical and everyday life. Walking through the streets of any city in Brazil, one is struck by the high number of pharmacies (farmácias). While the World Health Organization recommends one pharmacy per 8,000 individuals, Porto Alegre, for example, the capital of one of Brazil’s richer states, Rio Grande do Sul, has one for every 2,100 citizens (Pereira 2017). Some researchers speak about a “culture of medications” (cultura do remédio) in Brazil—an extreme willingness and desire to consume pills and other therapeutic products. Some researchers link this trend to the growing middle class, a higher life expectancy and the extremely rapid aging of the Brazilian population.

However, they also point to the underregulated influence of the pharmaceutical industry for the creation of the “culture of medications” (Pereira 2017). Even the current profound financial crises did not result in a decline in the consumption of medications: “In 2015, at the height of the economic crisis, the pharmaceutical market was the fastest growing industrial sector of the Brazilian economy, growing 8.3 percent while all other sectors were largely declining,” observes Patrick Burton in 2018 in the online journal Pharma Boardroom.

Fine-tuning

The conversation between the resident and the older woman’s children is predominantly about the family’s compliance with prescriptions, and it reflects the dependence on drugs as a solution. The family and the doctor mostly discuss, evaluate, and adjust an absent-minded body. They change the medications, and that, first of all, they measure against the older woman’s behavior—signs that the family interprets, and based on their accounts, the resident then analyzes. The reading of signs results in a constant alteration of medications and dosages, testing dosages in line with the progression of the disease and the effect of multiple, interacting medication—two kinds of signs that often cannot be separated from each other.

A family’s income further shapes fine-tuning in important ways. All health professionals we interviewed for our study were aware of the limited choices of available medicines for low-income families—and the prescribing doctor carefully chooses among medications that are either free or available at lower costs through the government program Farmácia popular, steering clear when possible of expensive drugs. Some geriatricians we interviewed said that in the end, the effects of the cheaper medications are the same. However, some lamented that poor people do not get the best medications but the cheapest options—often drugs with more severe side effects than the more expensive ones.

Pharma-literacy

A second point that immediately calls attention in the account about the old woman with Alzheimer’s is the large number of drugs prescribed in an unsettling flow of consecutive and abstract drug names. One can feel that the daughter gets confused sometimes (D: “The Hidrocloro is for the stomach, right?”; Dr. C.: “The Hidrocloro is a diuretic…”). It was astonishing for us the way in which family caregivers were actually able to follow the language of the resident’s questioning. Widespread pharma-literacy is a quite common phenomenon in Brazil. And although the knowledge does not always match the knowledge of a doctor, many Brazilians know a lot about medications. Constant media coverage, public health campaigns, and the prevalence of medications as an everyday topic of conversation fuels their knowledge.

The Pharmaceutical Self

The story about the older lady also points to what we want to call the “pharmaceutical self.” This concept describes the way in which others relate to the person with dementia and how she or he relates to the world through the use and the effects of medications. And although medications are not the only vectors, they play an important role in defining how others relate to who the elderly woman is and has been. At different points in the account of the elderly woman’s dementia, her social life quite easily is reduced to physiological and biochemical events. For instance, when the daughter explains her brother’s difficulty in getting his mother’s pension for his expenses (he is unemployed and lives with his mother), the resident answers: “So you are having difficulty buying the meds?”

Another example is when the daughter tells the resident about the challenge she faces in accepting the untidy, dirty parts of the life of someone with dementia. The daughter exclaims: “she who was always so vain!” and the resident answers: “So, her feces are solid, right? You give Quetiapina 25 in the afternoon, and 100 at night …” The horror of the situation described transforms into a clinical concern of possibly unhealthy bowel movements and which medications to take, even though that specific resident could be described as a caring, sensitive individual.

The tiny examination rooms. Usually doors are left open and residents and more senior geriatricians join ongoing examinations in semi-privateness.

While this clinical gaze risks reducing the old woman to merely a body in decline, other pharmacological practices more strongly seem to connect her to society. For instance, through the act of prescribing the contested specific dementia medications, the resident relates to the effect of the drugs that are supposedly connecting the old woman more to her surroundings. That effect is now measured in activities of daily living, after cognition has been abandoned as a primary therapeutic goal by the pharmaceutical industry. During the time we made our observations, these expensive dementia medications were distributed for free but only after a complex bureaucratic process, and only when the diagnosis was Alzheimer’s disease, rather than vascular or mixed dementia.

****

The consultation with the elderly woman and her family continued in a dramatic way. The unemployed son who was caring for his mother, but was not able to get hold of her pension, finally started to speak up, in an increasingly agitated way. He complained about the lack of recognition he received for his work, because some of his siblings and, especially one brother, were accusing him of having an easy life and of merely wanting his mother’s money. He described in detail the difficult, and sometimes disgusting, work he had to do—traditionally female work—that went unacknowledged by his family. He continued to scream, while other residents and one of the senior geriatricians came into the tiny room to try to calm the man down. The man started to cry. He had had to scream and interrupt the ritualized protocol to break out of the medication-centered consultation and make people hear his suffering. In this situation, the idea of a pharmaceutical self is not only deeply relational but life-sustaining. The lack of state interventions in Brazil, for which, increasingly, medications are used as a substitute further aggravates the dramatic situation. After this episode, the son was prescribed an anti-depressant.

The elderly woman would not survive without the family members who care for her, since there is little available space in public assisted-living institutions. The structure of many of those facilities undermines individual ways of living, often with the help of heavy administration of medication. Other institutions like day-centers or homecare exist, but often lack funding. Private solutions like maids (empregadas) or the growing number of caregivers trained in senior citizen programs can help families deal with daily care, but this is an increasingly expensive option. Ultimately, the medicated family is both the central caregiver and patient.

Winter 2019, Volume XVIII, Number 2

Annette Leibing is a medical anthropologist and full professor at University of Montreal. Her research focuses mostly on issues related to aging, by studying—as an anthropologist—Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s in different contexts, prevention of dementia, aging and psychiatry, pharmaceuticals, elder care and, stem cells for the body in decline, among others.

Cíntia Engel is a doctoral student at the Department of Anthropology at University of Brasília (UnB). She studies dementia, medications, and caregiving in Brazil. She is currently doing a doctoral exchange program at University of Montreal.

Elisângela Carrijo is a doctoral student at the Social Work Department at Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC). She is studying aging-related health care and social policies in Brazil. She is currently doing a doctoral exchange program at University of Montreal.

Related Articles

Video Interview with Flavia Piovesan

Flavia Piovesan is a member of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Professor of Law at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo and 2018 Lemann Visiting Scholar at the…

Aging: Editor’s Letter

There is no smell of pungent printers ink permeating my office. My interns—Sylvie, Isaac and Marc—are not scrambling to find FedEx boxes to send out ReVista issues to authors and photographers all over the world. I cannot feel the silken touch of the printed page…

A Story of Agricultural Change

Francisca Hernández García, 92, lives in San Miguel del Valle, a town of around 3,000 inhabitants in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, an hour east of the capital city. She is one of the few remaining…