Living Between Distant Shores

A Decade Reading Latin American Literature in East Asia

Esta mecánica, [la de depender del estado] de alguna manera, desoreja a los escritores mexicanos. Los vuelve locos. Algunos, por ejemplo, se ponen a traducir poesía japonesa sin saber japonés y otros, ya de plano, se dedican a la bebida. (2666 161-162, my italics) (This dynamic [of depending on the state], somehow, emasculates Mexican writers. It makes them crazy. Some, for example, set out to translate Japanese poetry without knowing Japanese, and others, quite simply, take up drinking).

The lines above take place in Mexico City. We are in the world of the late Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño’s masterpiece of a novel, 2666, and a Mexican character is describing—to his interlocutors, literature scholars from Europe—that one of the signs of the intellectual malaise that afflicts some Mexican writers is an inexplicable desire to Translate Japanese poetry without knowing any Japanese. The lines quoted above are only a tiny fragment of a massive novel, and yet they have has stuck with me all throughout my graduate studies.

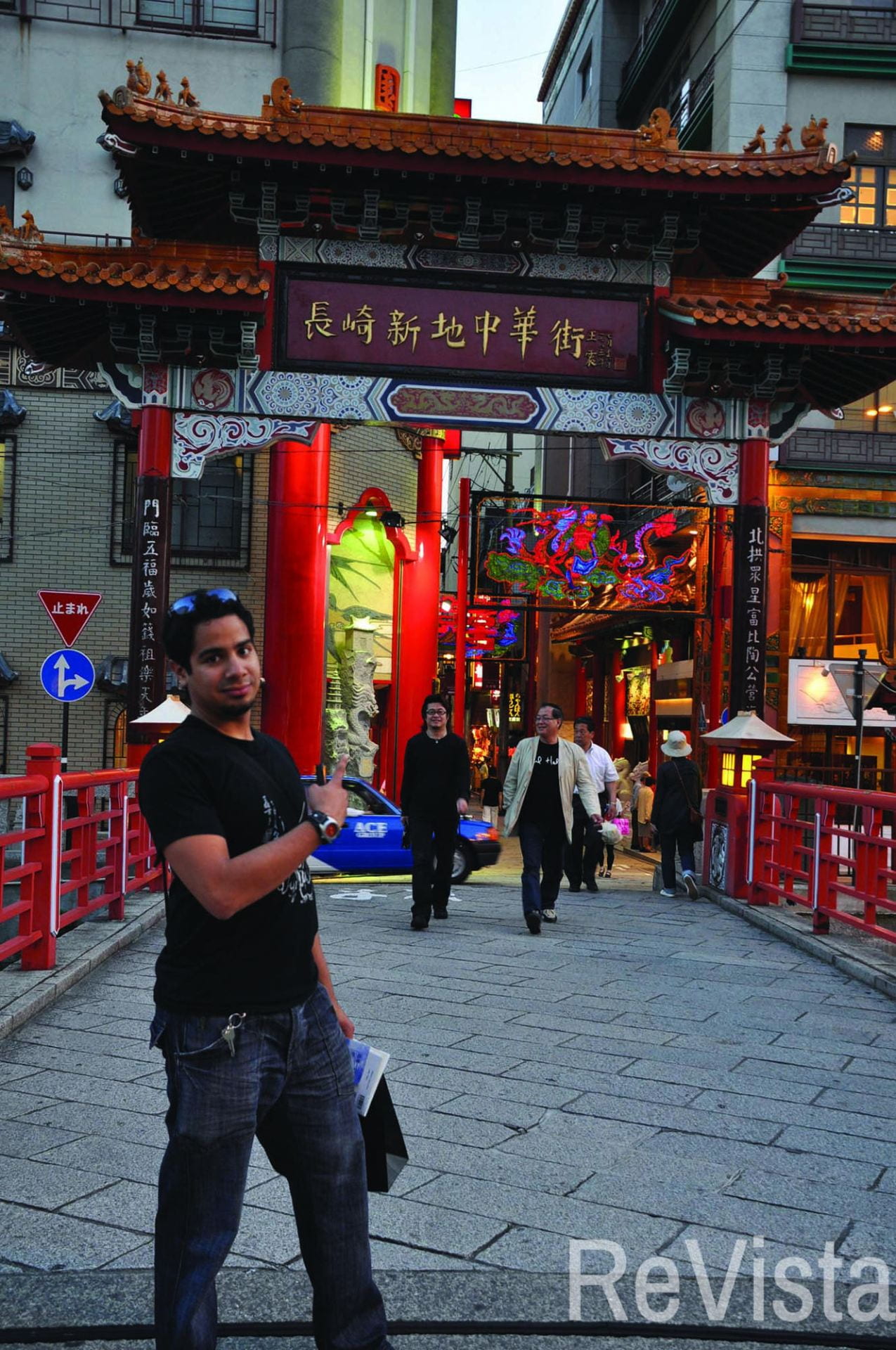

The scene from this novel takes place in the Mexico of the 1990s, but I read it neither in Latin America nor at Harvard, but years ago, when I was still a Master’s Degree student at the University of Tokyo. The café where I immersed myself in Bolaño’s world was in the middle of Tokyo, on an avenue facing the outer moats of the Imperial Palace. Less than a five-minute walk from that intersection, there stands the Tokyo branch of the Centro Cervantes, where, back then I—a Spanish-speaking student living in Japan—used to borrow a weekly dose of Latin American fiction from its vast library. The Centro Cervantes at Tokyo is a six- story building, housing a library and, one floor above it, a Spanish restaurant where you could have one of the best paellas in Tokyo. I would go there Saturday mornings for a literature fix, and then take the stairs one flight up to eat a Spanish lunch while listening to flamenco music.

Back then, as a Master’s student, I had no idea of what the future held, but some years later—after I became a Ph.D. student at Harvard—I visited all the other Centros Cervantes in East Asia: the stately branch in Beijing, an annex of the Spanish embassy; the branch in Shanghai, embedded in one of the fanciest parts of the French Concession, within walking distance of that odd block where the American and Iranian consulate almost face each other; and the minuscule branch in South Korea, comprised of a couple of rooms in a university office, a budget operation that opened during the recent years when the Spanish economy almost collapsed and has thus remained—regrettably—stunted.

Those centers are my reflections of Latin America and East Asia. Like walking into an air-conditioned room in the middle of a sweltering summer or huddling into a reading room with a fireplace to escape from the Cambridge winter, walking into these centers from streets with signs written in letters such as 浮浮浮浮, or meant more than a change in location: it was a change in mindscape, a complete reversal, soothing, coming back—however far away—to the mother tongue even as for the past 20 years I had lived in voluntary exile from the Venezuelan regime.

•••

But I get ahead of myself. I was writing about Bolaño’s 2666, and that passage where the Chilean-born novelist says— unprompted, untriggered, and out of the blue—that Mexican writers who write translations of Japanese poetry without knowing any Japanese have one too many loose screws in their heads. What was Bolaño talking about? Bolaño was writing about Octavio Paz. Or, rather, he was mocking Octavio Paz.

At least that is what—after having read hundreds of pages by both Bolaño and Paz—my dissertation research is increasingly suggesting. Se ponen a traducir poesía japonesa sin saber japonés, Bolaño would know: he was still living in Mexico City in 1970, the year in which Paz published the greatly edited—and much more widely sold—second edition of the book that was the Mexican writer’s longest translation from Japanese literature: his Spanish-language translation of Matsuo Basho’s classical haiku narrative The Road to the Deep North, or, in Paz’s Spanish, Las sendas de Oku.

Octavio Paz’s fascination for East Asian poetry predated the 1970 edition of Las sendas de Oku by at least two decades, and his interest in East Asian culture goes back even further. Having lived in India and Japan for the first time as a diplomat between 1952 and 1954, Paz met a young Japanese diplomat in Mexico in 1955 who would go on to help him translate into Spanish the haikus of Matsuo Basho. The little book came out in 1957, but it was not until 1970 that Paz—now, after all those years, working alone—revised the translation of the book and recreated many of its haikus, made them his own poems. Without knowing any Japanese. Octavio Paz: Mexico’s one and only Nobel-prize winner, its national poet, was bête noire for Bolaño and the poets of his coterie; no wonder Bolaño would feel inclined to mock his translational overreach.

And yet, in Latin American letters Octavio Paz is not alone. During the 20th century, for a Latin American writer to be interested in Japanese literature was not an oddity, but a common step in his or her poetic development. Jorge Luis Borges, in an early book review of a translated Japanese novel, is casual enough to write, in his usual off-hand manner, that “Hacia 1916 resolví entregarme al estudio de las literaturas orientales” (“Around 1916 I decided to dedicate some time to the study of Oriental literatures”): 1916, that is to say, when Borges was merely 17 years old. Fittingly, during the 1980s, nearly 70 after that early encounter with Asian literature, Borges paid two visits to Japan. By then he had completely lost his sight, but this did not impede his perception of his beloved Japanese culture; as he would say in an interview during the 1980s, he could not see the temples, nor see the stone steles and their inscriptions, but he could touch them, and this tracing of his blind fingers over the smooth wood and rock provided a more intimate contact with Japanese culture. Blind, Borges composed his late-period poetry mnemonically inside his head, relying on poetic forms to hold already-composed verses in suspension while he went on to work on the new lines. This is how he wrote the original haikus collected in his last poetry collections, The Cypher and The Gold of the Tigers. This, by the way, is also how he translated a classic from Japanese literature, Sei Shonagon’s highly allusive essay collection The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon. Working from an English version, Borges and his wife would sink everyday into the world of the medieval Japanese court—described in the English language that Georgie had learnt as a boy from the British side of his family—and come out at the end of the day with pages of Borges’s succinct and elegant Spanish.

Like Borges, Brazilian poet Haroldo de Campos, debuting in the decade of the 1950s, was also fascinated with Japanese poetry, especially by the Chinese characters that it used in its writing system. He had a radical approach to poetry, and, along with his brother Augusto de Campos and the poet Décio Pignatari, founded the movement poesia concreta in Brazil. The Chinese script so fascinated de Campos that in 1977 he collected, edited and translated a whole volume collecting essays on the poetics of East Asian characters, Ideograma: Logica Poesia Linguagem(Ideogram: Logic Poetry Language). Some 15 years later, he would also translate—likewise without speaking Japanese—the Noh theater piece, The Feather Mantle. The renowned Uruguayan poet Mario Benedetti also composed poetry based on Japanese models. His late poetry collection Rincón de Haikus—fittingly published in 1999, as the new Asian century was about to begin—became a bestseller not only in his native Uruguay, but also in other parts of the Latin American continent.

Why did Japanese literature attract so many fans from the ranks of eminent Latin American authors?

There are limits to my ability to explain why it attracted them, but I can explain why it attracted me. It all started with the Chinese Cultural Revolution (no, really, it did). One of my parents’ closest university friends was a Venezuelan of Chinese descent. This man’s last name was that of a Chinese dynasty, so here I will just call him “Tang.”

Tang was like an uncle to me, an uncle from faraway lands. He would often visit our house, and stay over talking with my parents until the wee hours of the night. As a five-year-old, I was convinced that he was related to either Bruce Lee or Ultraman, or both, and I always asked him to spar with me, a request that he would often brush away with a hearty Latin American laugh. For us, in my family, he was el chino Tang, even though he had never put his foot on any part of the Asian continent, and even though Tang’s father, scarred from his exile, had not made enough of an effort to teach his son any Chinese. The el chino moniker was given to him in the Venezuelan manner, without racial overtones, the same way that in my family I was called el negro, and my cousin el rubio.

Of course, Tang was not alone; there have been whole generations of Chinese and other East Asian immigrants to Latin America. I know about that now, but back then I was still a kid, living in the surreal peaceful family life of pre-Bolivarian Revolution Venezuela, and el chino Tang was the only Asian person I knew, and, man, was he interesting. Following that, my family moved to the United States for some years. I picked up English, and, in the way that many do, in picking up a new language I also picked up, without noticing, new ways of seeing. And before I knew what happened, my family moved back to Venezuela during middle school, and there was a parilla with el chino Tang, and there was his Hong Kong story.

Hong Kong. After many Hong Kong movies, three Hong Kong visits, and the whole oeuvre of the director Wong Kar-Wai, my heart is convinced, even as my mind knows better, that the best neighborhoods of Caracas—those neighborhoods built in the modern style and which were, once, the promise of a better tomorrow now betrayed—were trying to copy the now nostalgia-ridden modernism of Hong Kong architecture: skyscrapers built on a tropical island fighting the marine wind and water. El chino Tang traveled to that city for the first time in his life when he was close to 40 years old, to meet the estranged side of his family that his own side had not met since the Cultural Revolution. In Hong Kong, my uncle Tang explained, all sorts of Asian and Chinese people gathered, and many of them did not speak the local dialect, so in order to communicate they would trace Chinese characters with their fingers on the palms of their hands. Speaking, writing, to each other in this way, a sort of communication was achieved. With no Mandarin or Cantonese, uncle Tang lived for a whole season in Hong Kong, and when he returned to Venezuela he marveled his nephew with stories of the island. “You could live there too,” he said to me one of those times. “You would just need to know a dozen of Chinese characters to get by. They would look at your face and think you’re from deep in Inner China. You would just need to know some characters.”

Now, decades later, I know “some” characters, or just about enough to read novels in Japanese, Chinese and Korean. Japan is now my adopted home, having lived here for more than a third of my life. But it all started because one evening uncle Tang traced some Chinese characters on the palm of his hand, and then on the palm of mine. I would like to think that past writers from Latin America also have had experiences like this, and that is why they came back, now and again, to the Asia of their imagination.

Fall 2018, Volume XVIII, Number 1

Manuel Azuaje-Alamo holds an M.A. from the University of Tokyo and from Harvard University. He is currently a Ph.D. Candidate at the Department of Comparative Literature of Harvard University, and is writing his doctoral dissertation in Tokyo. He can be reached at mazuajealamo@fas.harvard.edu

Related Articles

From Vendedor to Fashion Designer

English + Español

Korean immigrants in Latin America are shaping and developing fashion economies there. Upon arrival, Korean immigrants to Argentina and Brazil may have been lonely, isolated and confused…

Shared Sentiments Inspire New Cultural Centers

English + Español

In the early afternoon of January 3, 2018, in the mountainous village of Shicang, Zhejiang Province, China, firecrackers burst into the air and flags waved in the wind as a parade of Clan…

Evidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st Century

A Review of Evidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st Century Contemporary Human Rights and Latin America On September 5, 1921, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, Hollywood’s then best-paid star, attended a party in San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel, drank...