Long-term Care in Chile

The Faces of Dependency

Chile is experiencing a process of accelerated population aging. This sentence is heard again and again in courses, seminars and speeches. Despite this, it does not always seem clear why aging is a problem.

Probably the dominant view so far has been the economic one. From this perspective, the problem lies in the increase of “dependency” in Chile, a term usually understood as the ratio between the inactive population (over 65 years and under 15 years) and the working population. Using this point of view, the increase in “dependency” poses a problem, since a smaller fraction of the population must pay for the “unproductive” members of society. The problem, then, is stated as one of “productivity loss” and “excessive spending;” as a result, the discussion is restricted to financing pensions and cost containment strategies in healthcare.

From a different perspective, the “other dependency”—or care dependency—addresses these same issues, understanding care as part of a broader discussion about social security. The “other dependency” refers to a condition in which a person has lost her functional capacity to a point where she cannot carry out the activities of daily living. In other words, dependents require help from another person to live their lives.

This other definition of dependency is also related to aging, although both terms are not synonymous; there are dependents who are not elderly and, at the same time, there are many elderly people who are autonomous (without dependency). However, in the current context of demographic transition, population aging is expected to be the main driver in increasing dependency, and the consequent increase in long-term care needs.

Long-term care is defined as actions taken to help people with dependency to live their everyday life. Today, there are many countries that have implemented long-term care systems in response to the growing needs of care of the population. However, in other countries—such as Chile—, the policy response to address the issue has been reactive and scarce, both in coverage and alternatives: the main strategy so far has been financing nursing homes, which currently offer services to a small fraction of the population. The bulk of the burden has been assumed by families, who have taken care of their dependents inside their homes, with little or no support from society.

This article delves into this problem, emphasizing the need that the country has today to look for ways to face the challenges of aging in a systemic and sustainable way. The country has responded in a fragmented manner to a problem that, to date, seemed exceptional; today we require new solutions for these changes.

Is There Any Poetry in Aging?

Chile is a land of poetry and poets. The only two Chilean Nobel prizes the country are in laureates in Literature, both poets. Gabriela Mistral was awarded in 1945; 27 years later, in 1971, Pablo Neruda received the same distinction. Other widely recognized poets are Vicente Huidobro, Pablo de Rokha, Nicanor Parra, Enrique Lihn, Jorge Tellier, Gonzalo Rojas and Raul Zurita.

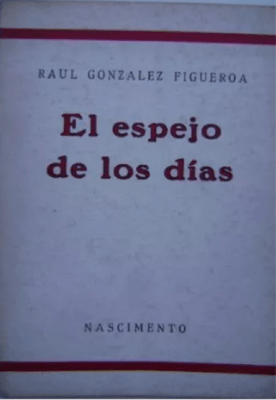

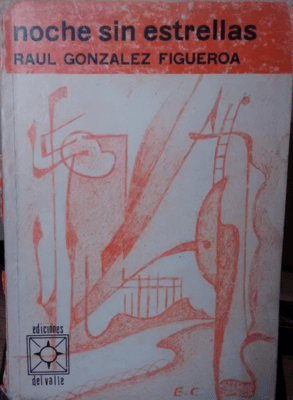

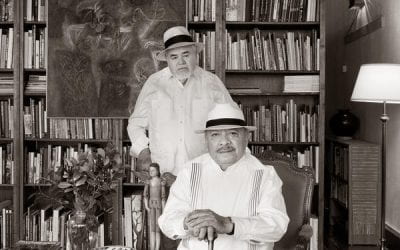

Raúl González Figueroa, born in 1931, came to swell the army of writers and poets in the country like others before and after him. Between the 50s and the beginning of the 2000s, he wrote six poetry books and a book of short stories. He received the Municipal Poetry Prize in 1972 for his work Angelica and the Butterflies.

González Figueroa could have been part of the list of illustrious poets of the country, recognized for their works. However, the reason for his recent recognition is different.

- Books published by Raúl González Figueroa.

In June 2016, some of the poet’s work began to circulate in the media. In particular, a fragment of his book The Mirror of the Days published in 1978, was reproduced in local newspapers:

“To remember is to find again / our forgotten body / our body / that tomorrow / will also be a memory / floating in the memory”

This beautiful verse of one of his poems was not reproduced in the newspapers’ cultural pages, but in the crime section. His name, along with the names of two other elderly men, came to light as a result of a police investigation.

On April 28, 2016, three elderly men were reported dead in a nursing home in southern Santiago. The investigations to clarify the causes of these deaths showed that, in all cases, there were signs of malnutrition and lack of care. The information published in the media revealed that Raúl González Figueroa had gone nine days without consuming any food prior to his death. He had not received the medications that were supposed to be administered. González Figueroa, who was suffering from Alzheimer’s, had been living in this residence for several months. He needed help to perform even the most basic activities of daily life, including eating.

His death reignited the alarms regarding the reality of many people, mostly older people, who have lost their autonomy and need help to live their lives, especially those who live in institutions.

Poor living conditions of institutionalized older people in Chile did not begin with the death of González Figueroa. Unfortunately, they did not end there either. From time to time, the national press publishes news related to the issue: clandestine establishments, homes in poor conditions, abuse and deaths due to neglect.

All these cases should encourage society to reflect on how the country will face an increase in long-term care needs in the coming years. This reflection should include strategies on how to ensure the quality of care institutions—homes like the one where González Figueroa died. However, it is also to think about the magnitude of this demographic change and the need to implement different ways of offering long-term care services to people with dependency beyond institutionalization. Our country must provide opportunities to people who require care, especially considering the rapid aging of the population, so they can live high-quality lives. Aging with poetry.

Who Cares for the Caregivers?

Although institutionalization has been traditionally seen as the public policy answer (in some cases only) to deal with long-term care, all countries—and Chile is not the exception—have a scheme that constitutes the backbone of long-term care: informal caregivers.

Informal caregivers are a fundamental pillar of the long-term care structure: in Chile, nine out of ten people who provide care services are informal caregivers, usually a relative who lives in the same house with the person who receives these services. The story of Ana (a fictional character) helps to illustrate what it means to be an informal caregiver in the country.

Ana, 55, has been taking care of her mother for the last eight years. At first, Ana thought that her mother’s health problems were not that serious. She decided to continue working full-time and pay more attention to her mother’s routine who, for several years, lived alone without complications. Over time, her mother’s condition worsened and her need for care became increasingly evident. Finally, Ana and her brothers decided that their mother could no longer live on her own.

The brothers discussed the possibilities; they all had families and jobs. They think of themselves as middle-class families: they lived a decent life, although constantly dealing with the economic situation and increasing debts. One possibility was to send her mother to a private nursing home— so-called senior suites. However, Ana and one of her brothers did not think their mother should end her days in a nursing home and they ruled out this option both on emotional and economic grounds. A government-run nursing home was out of the question; they had heard too many news about their bad conditions and problems. In addition, since many of these establishments use economic need in their selection, they probably would not be eligible either. In this situation, the only feasible alternative was that one of them would take care of their mother. The situation caused a rift between Ana and her brothers. Ana ended up taking responsibility for the care of her mother.

She stopped working, having an immediate impact on her household finances. Although her brothers help her economically, her mother’s condition generates more and more expenses. One salary doesn’t go far enough with two children. Ana spends an average of 16 hours a day on activities related to her mother’s care, splitting her time between preparing meals and feeding, cleaning the house, keeping her company, giving medicines, dressing and undressing, and taking her to the bathroom.

Ana says she would like to work again, but for now, that’s not a possibility. Since she started taking care of her mother, she has not taken vacations. The one time she decided to go out with her husband and children, she worried the whole time because she did not want to leave her mother alone and feared that something would happen in her absence. This situation, plus as well as the fact her mother now lives with them, has worsened their relationship with her husband.

Ana has begun to resent this lifestyle for at least two years now. She complains about feeling tired and sick, but she doesn’t have time to see a doctor; her patience is always taxed. But she feels bad about her resentment because she truly loves her mother. She thinks constantly about her mother’s death. Ana is depressed. Everything she does and doesn’t do takes her deeper into that state. She feels that every day she looks more like her mother.

Ana’s story is real, even if she is a composite character. Ana is, statistically speaking, the country’s average informal caregiver. Her story, although fictional, reflects the current situation of informal caregivers in Chile. The data shows a reality that today remains invisible to the eyes of society and policymakers. Long-term care is considered a private issue. a situation that occurs within the family bubble. Consequently, there is little information about informal caregivers. Without statistics, the problem is difficult to access and the solutions are difficult to design.

Towards an Integrated Response

The stories of Raúl and Ana show a face of aging that is known but we refuse to accept. Both cases reflect the way in which, until today, the country has approached the situation of people who require long-term care, making people choose between institutionalization and informality.

These cases can be seen as isolated cases, extreme situations. However, we know that, due to the accelerated process of population aging in Chile, these situations will change from being the exception to becoming an increasingly common reality.

Up until now, our society has struggled— with persistence and love—with the issue of caring for people with dependency. The rapid increase in the aging and dependent population forces us to think today about more effective, efficient and sustainable solutions. We must move towards the implementation of a national system of long-term care, which allows us to coordinate the several initiatives that have emerged over time. Additionally, this system should allow the expansion of the current supply of services, ending today’s dilemma between institutionalization and informality, and moving towards a system that provides a “continuum of care” and options.

It is not only a matter of providing better coverage of long-term care services in Chile but of offering both dependents and caregivers alternatives that allow them to choose what best suits their needs, in order to live their lives with dignity. Persistence and love will remain present; a long-term care system doesn’t intend to replace personal affections, but to recognize an issue that, whether we see it or not, affects us all.

Winter 2019, Volume XVIII, Number 2

Pablo Villalobos Dintrans works as international consultant working on public policy and public health. He has a background in economics, and holds a doctoral degree from Harvard School of Public Health ’18. His current research focuses on health systems and long-term care policies.

Related Articles

Video Interview with Flavia Piovesan

Flavia Piovesan is a member of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Professor of Law at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo and 2018 Lemann Visiting Scholar at the…

Aging: Editor’s Letter

There is no smell of pungent printers ink permeating my office. My interns—Sylvie, Isaac and Marc—are not scrambling to find FedEx boxes to send out ReVista issues to authors and photographers all over the world. I cannot feel the silken touch of the printed page…

A Story of Agricultural Change

Francisca Hernández García, 92, lives in San Miguel del Valle, a town of around 3,000 inhabitants in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, an hour east of the capital city. She is one of the few remaining…