Lowering National and International Laws into Amazonian Hills

Seeking Territorial Rights

Thousands of Amazonian indigenous peoples converged on Quito in October 2019, led by Jaime Vargas, the president of Ecuador’s national indigenous confederation CONAIE. Ostensibly protesting increased gasoline prices along with other organizations, the Amazonian groups were focusing on the government’s failure to advance dialogue on existing human rights laws, particularly those related to territorial rights and natural resource development.

Though desirous of maintaining their distinct cultures and languages, those from the Amazon region have little interest in separating or isolating themselves from national governance or economic development. They simply want to participate as distinct but equal peoples. Dialogue and consultation on Ecuador’s impressive 2008 Constitution, as well as earlier national legislation and ratification of international human rights norms has fallen way behind. The 2008 constitution greatly expanded collective land and self-determination rights through a new category, Circumscribed Indigenous Territories (CTI). From a legal perspective, CTI self-determination claims simply seek what human rights lawyer James Anaya writes is the “foundation” of human rights, self-determination, currently linked to lagging advances on the related right to Free, Prior, Informed Consent (FPIC) for any development work or other territorial interventions.

As another indigenous rights lawyer Jérémie Gilbert clarifies, such self-determination simply seeks the internal “right to effective political participation within States’ borders,” not some controversial external claim regarded as “separatism.” These rights were even more recently supported by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights’ 2015 report Indigenous Peoples, Afro-Descendent Communities, and Natural Resources: Human Rights Protection in the Context of Extraction, Exploitation, and Development Activities.

But, in Ecuador no local CTI request has yet been recognized. Nor is appropriate prior consultation acceptably carried out. While Jaime Vargas warmly accepted President Lenin Moreno’s offer for open dialogues, specific territorial self-determination claims often require historical, social and cultural contextualization. That is: How do indigenous peoples understand their “territory?” How long have they claimed it? How might others understand it? Since land and resource claims will be discussed under new, broadly democratic, laws—not simply denied or awarded by the state as in the past—ethnography and history can help to bridge such logical questions.

Early Territorial Claims: Arajuno

- Arajuno: Puka Rumi botanical garden. Photo by Ted Macdonald

- Arajuno: Puka Rumi botanical garden Ayahuasca. Photo by Ted Macdonald

One large Ecuadorian Amazon indigenous community, Arajuno, located on the border between Pastaza and Napo provinces, has submitted a CTI claim and awaits dialogue. With and for the local indigenous federation, the Association of Indigenous Communities of Arajuno (ACIA), as well as the founders of the local natural resource cultural center, Puka Rumi, I am currently helping to detail their historical, social and cultural responses to the broad questions above, largely through recent and earlier (mid-1970s) conversations and ethnographic work, as well as written sources.

By tracing the area’s settlement and growth largely from atop the hands and through the eyes of Arajuno’s founders and current leaders, many of whom are direct descendants of the original arrivals, a culturally defined understanding of territory and its importance is clear. Understanding kin-based and spiritually-shaped space, as well as simple long-term residence, help to support not only the historical claims of Arajuno but those of many other indigenous communities of the Upper Napo region seeking formal recognition of self-determination through their CTI. In brief, past history can assist future dialogue.

- Arajuno Association of Indigenous Communities (ACIA) meeting. Photo by Ted Macdonald

- Andean Kichwa visiting Puka Rumi botanical garden. Photo by Ted Macdonald

Early Arrivals: How and why?

Amazonian origin myths often cite primordial emergence from water, stones or animals. Arajuno’s leaders, however, describe more historically precise early arrivals. In 1912, Domingo Cerda, a powerful yachaj (shaman) arrived with his family and settled for a while at the foot of a high hill, Pasu Urcu. He had left his principle settlement, or quiquin llacta, near Tena/Pano, on the Upper Napo when police pursued him on charges of witchcraft. A bit later, and similarly avoiding police, another yachaj, Roque Volante Lopez, arrived from Apayacu, also close to Tena, with his family. At the time they were also in debt to usurious White merchants, or patrons, who provided essential merchandise at extraordinary costs, incurring debts generally paid off through gold panned from riverbanks, and sometimes reduced through domestic labor at their estates.

Viewing Pasu Urcu from above, without talking to Roque or Domingo’s descendants or observing their residence, they appeared to be simply “running away,” hiding in the forest from police and patrons. By contrast, coming down to the ground, exploring residence and tracing movement over a longer period, unfolds indigenous territorial priorities and examples of agency. Each stayed for a while, gathered foods, fished, and hunted. Later, after clearing themselves of police charges and gradually paying down debts to the patrons, they settled more permanently, establishing a residential kin group referred to a muntun. Apparently drawing on the Spanish term for heap or mound, and contrasted to the hierarchical chiefdoms of the highlands, the Amazonian muntun, was easily and frequently misunderstood and dismissed as “savage nomadism” by missionaries and government officials who sought to sedentarize and “civilize” them. Meanwhile, the forest residence muntun was fully accepted by patrons, who simply hoped to secure goods as debt payment from indigenous “underlings.” Most outsiders, in brief, showed little interest in or understanding of indigenous residential preferences or their sense of territoriality.

Domingo and Roque were, in fact, simply replicating an ancient residential pattern, along with others who settled alongside hills at several points up and down the Arajuno River. Pasu Urcu gradually became their purina llacta, or walking settlement, richer in fish and game than their main settlement, quiquin llacta, and freer from external demands and internal social tensions. As the frequency and length of stay increased, subsistence gardens, chacras, grew, creating more stable and dependable secondary residences. For this Pasu Urcu and its adjacent environs were in some ways ideal. Although risks of possible attacks by neighboring Huaorani along the right bank of the river, the surrounding forests and rivers had much more fish and game than the more densely populated area of their quiquin llacta. Such expansive territorial movement, often perceived and misunderstood as “flight” in the Upper Napo, can be traced back Spanish colonial times.

- Margarita Lopez, yachaj’s daughter, explaining Puka Rumi and Pasu Urcu to Andean Kichwa. Photo by Ted Macdonald.

- Margarita Lopez, yachaj’s daughter, explaining Puka Rumi and Pasu Urcu to Andean Kichwa. Photo by Ted Macdonald.

Territory and Spirit Ties

Perhaps the most significant geographical and territorial marker was Pasu Urcu itself.

Like most such hills, inside Pasu Urcu spirits, supai, were understood to reside. They were regarded as the masters of the surrounding fish, birds and other animals, and managers of the garden lands. Women easily and carefully related to garden spirits. Gaining access to the area’s wild game required strong and long-term ties with the supai. They sometimes wandered in the forest during the day, but were most frequently met through dreams, understood as a time and space where all spirits and human souls wandered about in the night air.

Arajuno resident Jorge Tapuy’s early dream illustrates the initiation of essential supai relationships.

In a dream a friend and I were walking inside Pasu Urcu. It was not as it appears from the outside. It was a city, just like Quito .. with houses, stores, music, windows, and all sorts of animals and spirits sitting by them. Suddenly, a beautiful supai woman with long black hair and strings of beads around her neck and wrists approached us and asked me to follow her. As I left my friend, the supai asked why I had not come to marry her earlier. Then she told me that we must visit her mother and ask permission. I was very nervous but still followed her as she explained how I should approach her mother and what I should say to her, to demonstrate respect and abilities.

After passing through three doors, we finally entered her mother’s room. She sat at the edge of an enormous bed, all hunched over with her hair and eyes turned toward the floor. I couldn’t see her face; her body was covered with bristles, like a porcupine. We sat silently on the bed beside her for a few minutes. Then the supai woman nudged me, urging me to speak. I was scared but I finally told her mother that I wanted to marry her daughter.

But then her mother retorted that I could not marry her daughter because the she was huayusamanda … a regular drinker of the herbal tea, huayusa. To live with her I too would have to drink it. I replied that I already drank much huayusa and would drink whatever amount she gave me. Then the old woman suddenly lifted her head and a pair of glowing dark red eyes stared up at me like two flashlights. She said that if that’s true, I could marry her daughter.

We then left, and I woke up. That was how I met my supai huarmi, spirit wife, who is still with me.

After that, Jorge explained that, when told of the marriage, the spirit woman’s father made wild game accessible. To strengthen ties, Jorge and the master male supai, Amasanga, met regularly, not simply at dawn while drinking the mild huayusa, but also at night as they occasionally shared supai favorites, the strong forest vine beverages, ayahuasca or chirihuaysa. Despite current imagery of hallucinogens, Jorge explained that indigenous people did not consume the drinks for pleasure, but simply to strengthen relationships. Progressively, he became “one who knows,” a yachaj, or shaman. Most male residents sought similar ties with local supai. Though some human wives argued that they might lose their husband, most supai huarmi did not affect the human marriages. But to be very closely tied to supai required much fasting and hallucinogens. Those who did so most frequently were regarded as strong shaman, or sinzhi yachaj, often becoming the principal claimant to the surrounding lands and resources and, thus, the principle social focus of their muntun.

Other muntun members were, of course, the sinzhi yachaj’s immediate family. But, due to the prevalence of illness and death at the time, nuclear families were generally not large. Those from similarly truncated kin groups joined muntuns, often seeking ties with the respected yachaj or invited to do to strengthen the group. Consequently, social life, as well as resource access, was centered on the residence group, not simply blood kin. And members regarded the muntun as coterminous with their territory.

Sometimes and at some places, of course, hunters walked across streams or through thickets and were seen as trespassing across borders. This sometimes led to disputes. However, in many such cases, the principle yachaj of each muntun gathered, imbibed ayahuasca, called in their respective supai, asked them to clarify boundaries, accepted their agreed upon frontiers, informed the communities and settled the matter. In brief, consultation and consensus over land rights was common, and succeeded.

Unfortunately, access to natural resource was not the only assistance provided by supai. They also served as nocturnal protectors from or agents of attacks between competitive yachaj. Attacks led to illness transferred by supai darts, or biruti. The following account, related by another friend, Alonso Andi, clearly illustrates external feuds as well as internal muntun solidarity.

As a young orphan, Alonso, wandered a bit, but later settled close to the Pasu Urcu muntun’s head shaman, Pablo Lopez, and was gradually treated as another son. One of Alonso’s long stories is particularly appropriate to the combined sense of community and territory.

One day, while working in the chacra, my sister was calmly sucking on some sugar cane. She suddenly became ill and vomited blood. We rushed her to Pablo’s house, where he quickly took ayahuasca and began the cure that evening. With the help of supai, he quickly saw a biruti inside of her. But as Pablo began to suck it out, the biruti darted away and lodged itself inside him, purposely. It was a plot to kill.

The girl, most agreed, had been attacked by a recently arrived downriver yachaj, Velarez. Aware that Pablo was the most powerful yachaj in the area, Velarez knew he would be chosen to cure the girl, so he asked supai to easily pass the dart to her. Velarez, however, was not popular. He had recently arrived in a downriver muntun, Puni, after being chased out of more distant settlements …Pacayacu, Upper Villano, and Boca de Villano. Many of his new neighbors disliked him and they told Pablo that Velarez, was delighted with his trick, saying had duped Pablo and would soon take his women away. What enraged Pablo was that, earlier, he had cured Velarez, who was somehow envious and simply wanted to eliminate Pablo, not discuss anything.

Pablo, though initially furious with Alonso, calmed down and asked Alonso and another relative, Vicente Andi, to travel down the Curaray River to Boca Villano and bring back a powerful yachaj Bancu Acevedo, one of Pablo’s close friends, who had trained and guided his fasting to become a very powerful Bancu yachaj.

After several days paddling downriver and searching around the area, Alonso and Vicente finally met Acevedo and they all set off for Arajuno. As they poled upstream, Acevedo called in his supai to see if Pablo was still alive, and to clear their path of any dangerous supai perhaps placed there by Velarez.

Five days later, they arrived in Arajuno. But Acevedo was unable to cure Pablo. Fearing attacks from Velarez, Acevedo packed up Pablo took him and his family back to Villano. But after a month there Pablo did not improve. So, he asked Alonso and Vicente to bring him back, so that he could die at home.

During the trip, Alonso had a strong dream. Traveling down the Curaray River, a large tree filled with Chahua Mangu bird nests suddenly fell into the river. All the birds scampered from their nests, and sat atop the remaining unsubmerged branch. Suddenly they flew up together and raised the fallen tree.

The next day they met Pablo, who was heading upstream to meet them. They related the optimistic dream to him. But Pablo remained quite upset that, after having cured many in Villano long ago, no one there was able to help him. He feared that Velarez had beaten him.

However, on returning home, the people of Arajuno brought that dream to life. They said it was impossible to kill Pablo, since he was much more powerful. So, they gathered, took him to his house, where he began to call all of his supai towards him. With that help, Pablo then pulled out a pair of scissors from his body, the same ones that he had pulled out of Velarez when he cured him earlier.

This, all agreed, was the only weapon strong enough to kill Velarez. So, Pablo then handed the scissors over to his supai and dispatched seek out Velarez. He quickly fell seriously ill and died in Puni, where he had no local community support.

Alonso’s story clearly links Pasu Urcu’s yachaj to his muntun. Inter-muntun feuds were generally sparked by interpersonal fights and frequently blamed for sudden illness and death. Earlier, Yellow fever was one of the most frequently cited bituti in supai attacks. It had killed Roque, Domingoand many others. However, as treatments and vaccines were introduced, feuds decreased significantly. Local understanding added a social dimension. Vicente Andi explained that yellow fever, Quillu Ungui, could be heard in the forest. Quillu Ungui supai often emitted whistles or yelled, he said. To control these malicious, sometimes uncontrolled supai at about mid-20th century, the head yachaj from Arajuno and several adjoining headwater rivers met, drank ayahuasca and called in their close supai. The supai were then sent to capture many of the Quillu Ungui supai, and later trapped them in pool in the upper Villano River. Capture seemed to work. Yellow fever declined, and so did related feuds. Spirits who earlier functioned dramatically in both feuds and wildlife access, came to rest almost exclusively as the basis for claiming resource access, defining territoriality and assisting internal social relations.

Such ideas and actions illustrate that, earlier in the large previously multi-muntun area that now makes up Canton Arajuno, each group shared the sense of territory as those who first settled near Pasu Urcu. While feuding between yachaj clearly existed, other relations and actions illustrate dispute resolution across the currently wide territory, and the continued priority of natural resource access. It continued amidst significant outside arrivals.

Such ideas and actions illustrate that, earlier in the large previously multi-muntun area that now makes up Canton Arajuno, each group shared the sense of territory as those who first settled near Pasu Urcu. While feuding between yachaj clearly existed, other relations and actions illustrate dispute resolution across the currently wide territory, and the continued priority of natural resource access. It continued amidst significant outside arrivals.

As will be detailed in the forthcoming book, similar territorial interest persisted amidst what appeared to be major changes. The first was oil exploration and airport construction by Shell Oil Company (1942-1948), followed by the arrival of Protestant and, later, Catholic missionaries, who remained after 1955. In each case the new outsiders, despite obvious domineering imagery, new values and economic influence, did not truly understand or interfere with traditional territorial priorities. Later, an apparently radical territorial shift appeared in the 1970s. Colonization by Whites began in 1960 and increased during the 1970s as new agrarian reform laws pushed for the privatization of Amazonian landholdings and made demands for visible land use. This led many to seek private 125-acre lots and loans to purchase cattle, particularly in Arajuno then quiquin llacta. As lots near colonists were demarcated and privatized, many also did so, as kin-based neighbors in their purina llacta.

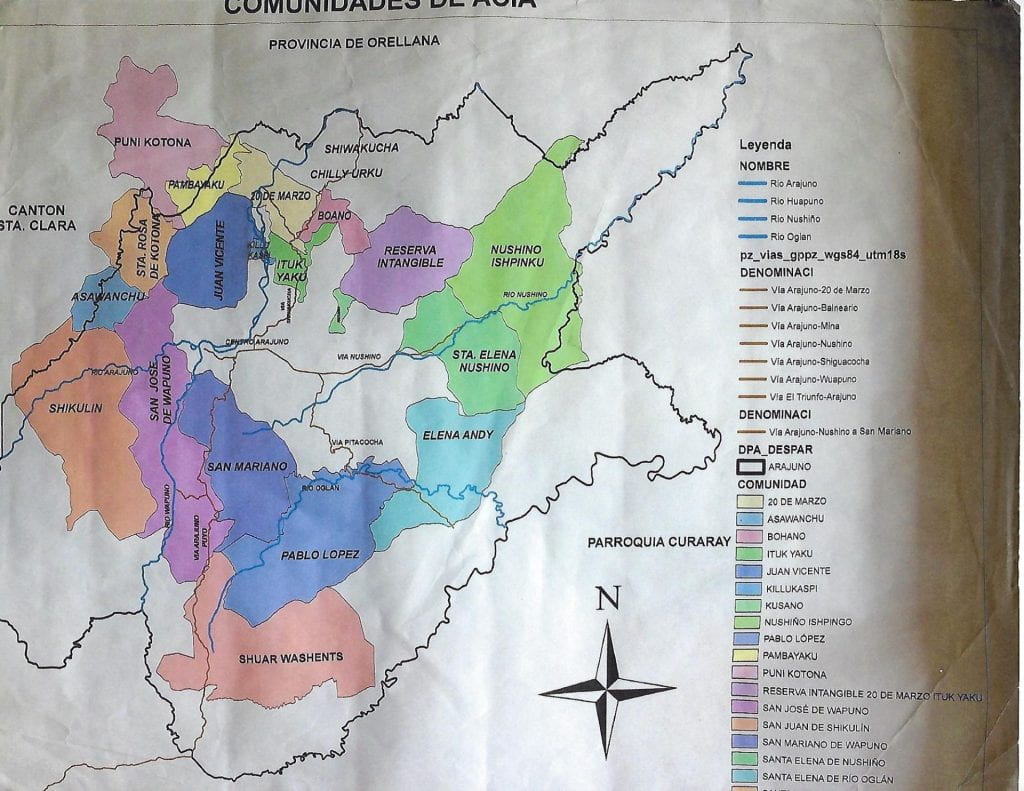

Years later in both areas, cattle disease and decreased economic demands led to a lesser demand for individual lots in interior areas. More important, in 1969, the indigenous federation ACIA was established, soon working to shift much of the purina llacta lands back to communal property to be shared by the families who originally moved there. Although such areas now contain some private family plots, the larger areas illustrate kin based territory (see map) In brief, though land titling suddenly and dramatically shifted, and remains so around the downtown area of Arajuno, the older muntun community-based cultural organization persists through much of the interior. This raises a question. Today, to what extent might such shared ancestral territorial interests persist as Arajuno seeks self-determination through the CTI?

Current Territorial Appearances

Riding into town nowadays, much seems to have changed. Maps, aerial photographs or a simple walk around town present a greatly modified landscape. About 8,000 people now live on the right bank of the Arajuno River in an urban municipality marked by parks, food and clothing stores, bars, elementary and secondary schools, a cooperative bank and several government offices. Beyond that, the large Canton Arajuno (national political unit) extends eastward to the Peruvian border and comprises 81 communities. The canton also includes the territory of their Huaorani neighbors as well as most of the Yasuni National Park.

Reviewing genealogies, Luis Canelos, Megan Monteleone, and Ted Macdonald. Photo by Aaron Kalischer-Coggins

Since 1992 the municipality now connects with the city of Puyo by a road, along which buses and trucks regularly ply hourly. The southeast border area is flanked by an Argentine oil company’s production facility and pipelines from wells near Boca Villano, where Bancu Acevedo once lived. Arajuno anticipates discussion regarding future oil development inside its territory. And a new Chinese-run lumber company now sits even closer to the canton’s border, awaiting logs.

At first glance, Arajuno’s original settlement appears to have grown like most urban areas, through a simple combination of local population growth and an influx of new settlers enabled by the road. In part, simple population growth explains many of the radical physical changes. However, despite increased numbers and urban growth, a high level of political and cultural continuity persists throughout the western part of the territory. There sit 18 communities. Amidst agriculture, animal husbandry and open forested areas, the kin-based indigenous residents continue to claim communal rights to land and resources, put forth largely by the directorate of the local federation, the Asociacion De Comunidades Indigenas De Arajuno (ACIA). Though such organizations are relatively recent political creations, their current claims and uses reflect the ancestral cultural and spiritual ties to land and resources reviewed earlier.

Unlike the early settlement days, there is now no internal territorial argument with the Huaorani, residing within Canton Arajuno, farther to the east and sometimes sharing kin ties and residence. However, the Huaorani currently illustrate some future problems. Currently debating oil development on their lands, new production was legally halted in 2019. But the court decision was not a final territorial rights victory, but simply an opinion that prior consultation has not been undertaken satisfactorily.

Though Arajuno’s historical territorial claims in the more densely packed area persist, individual choices have diversified the community. While many members of early the muntuns seek to continue their traditional unity, through shared cultural traditions (see Megan Monteleone’s article here) and continued territorial interest in their long-held purina llacta, others seek a different economic and social life centered on individual economic life. Like many such Amazonian and other previously isolated tropical forest communities, there is not a uniform view or future aspiration. Diversity is common, as illustrated by a recent New Yorker article on the famously unified and independent Kayapo nation in Brazil, or the violent land disputes currently arising amidst Nicaragua’s Mayagna, after Awas Tingni won a major Inter-American Court of Human Rights land claim in 2001. In each area, some views on land and economic priorities have clearly changed… and require consultation and negotiation.

- Arajuno wedding. Cesar Cerda, padrino, leads the dancing. Photo by Ted Macdonald

- Arajuno women happily dancing at a wedding. Photo by Ted Macdonald

But the large clusters of communal lands located around Arajuno’s center still reflect the earlier muntun purina llacta. Nearly all are regarded as communal holdings, surrounded by open forested areas with named after their initial claimants. They are often seen as nature preserves and frequently visited by students and scientists, as well remaining personalized spiritual and hunting territories by muntun members. In brief, despite all the changes, the sense of spirit-defined purina llacta persists, physically as well as culturally.

And the supai are still there, and matter. When the entrance road was recently constructed along a hilly ridgeline into Arajuno, engineers simply carved through an upriver hill, Huama Urcu, whose supai were linked to a close muntun. Later, a woman from Pasu Urcu, who had married a man for Huama Urcu, and her father suddenly fell ill. Both died. The presumed cause was an angry supai who was said to have bitten their necks like a buzzard, due to frustrated rage because his home had been partially bulldozed by contractors. Most locals desired the road, but they had not been consulted regarding the route. Now, national oil companies are working to persuade some individual communities inside Canton Arajuno, despite the demands of ACIA for broader consultation, negotiation, and consent.

Such communal preferences illustrate, simply but clearly, what is meant when Kichwa and other Ecuadorian indigenous currently invoke their desire for sumak kawsay, a “good life. ” Their aspirations are not utopic dreams or permanent tranquility. Rather, they simply seek a meaningful life realized through a degree of self-determination.

Spring/Summer 2020, Volume XIX, Number 3

Ted Macdonald is a Lecturer in Social Studies and Faculty Affiliate at DRCLAS, Harvard University. He has worked directly on Latin American indigenous rights issues and cases since 1980. Currently and in collaboration with Kichwa Indian community leaders, he is preparing an ethnographic history of territorial rights and self-determination in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

Related Articles

Amazon: Editor’s Letter

The Amazon is burning. The trees that have not been cut down are on fire. The crisis is now. When I began to work on this issue on the Amazon, that was pretty much my vision, and it was a real one. I was determined to make the magazine on the Amazon about…

How Democracies Die

How Democracies Die analyzes the main dangers that modern democracies face. As the authors warn, 21st-century democracies do not die in one fell swoop, in a violent way, by hands that do not always belong to the political system. On the contrary, modern democracies…

The Return of Collective Intelligence

My college Native American Culture professor, the Mescalero Apache scholar Inez Sánchez, told our class that we should regard the word “primitive” as synonymous with “complex.” I gained a better understanding of what Sánchez meant reading The Return of Collective…