Managing Peace

Private Sector and Peace Processes in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Colombia

Fourteen Colombian business leaders talk with FARC commander Manuel Marulanda “Tirofijo” in San Vicente del Caguan. Photo by German Encisco, courtesy of El Tiempo.

In a recent interview, a Salvadoran businessman recalled what ex-combatants of the demobilized Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN) told him when they met: “The worst mistake we made since [the government of president] Duarte was that we negotiated with politicians; we should have negotiated with the owners of this country, the business people.”

This assertion emphasizes the fundamental role business plays, and indeed should play, both in peace negotiations and the subsequent implementation of a peace agreement. Business controls and generates many of the necessary resources for building peace, by means of production and taxation. As a result, business decisions—to invest, produce, and hire—limit, condition, and shape the agenda and scope of peace negotiations. In addition, in many Latin American countries, the private sector has historically enjoyed privileged access to government decision-making, which increases its veto power over the policy process.

The evidence from three very different peace processes in Latin America supports these declarations. El Salvador, Guatemala, and Colombia all underwent internal peace negotiations in the past decade. While the Central American cases ended in peace accords—in 1992 in El Salvador and in 1996 in Guatemala—in Colombia, the peace negotiations failed in 2002. In each of the three cases, the domestic business sector played key, albeit quite different, roles. These case studies thus lend themselves to an exploration of the manifold ways in which business has responded to the possibility of a peaceful resolution of conflict and of the factors that shape the very different relationships between business and peace.

Just last year, Salvadorans celebrated the tenth anniversary of the signing of their peace agreements. Under the leadership of President Alfredo Cristiani (1989-1994), the government and the FMLN agreed on several institutional reforms aimed at broadening the political space, reorganizing the ill-reputed military apparatus and reforming the judicial system. Previous attempts at negotiating peace in El Salvador had failed, mainly because there was fierce resistance from the private sector. This raises the question: what made peace talks finally possible in El Salvador and how was the support of the Salvadoran business community ensured?

The answer may be found in a profound shift that occurred in the structure of the Salvadoran business community during the 1980s. The emphasis on the production of traditional agricultural export goods that had been the pillar of the Salvadoran economy gave way to increased diversification into new sectors such as commerce, agri-business, and financial services. While El Salvador is still not a model of a diversified economy, it has steadily moved away from being under the legendary control of 14 families. In practice, a new “modern” elite has emerged.

Much of this transformation was induced by targeted U.S. intervention. The creation of the Fundación Salvadoreña para el Desarrollo (FUSADES), which dispensed credit and supported activities in new sectors of the economy to the detriment of traditional products, played a key role in shifting the balance among sectors of the economy. The strategy was successful inasmuch as it reared many of the leaders of the new business generation who began occupying leadership roles in business associations and in government. In contrast with their parents, for this new business generation the Salvadoran conflict became more a matter of missed opportunities than one of principles. In fact, conflict imposed a great cost: the destruction of infrastructure, kidnappings, and lost investment all led to the realization that this was too high a price to pay.

Furthermore, conflict interfered with the consolidation of the new economic model that emerged under the label of Washington Consensus. Actively promoted by FUSADES, the model, based on principles of increased competition among economic actors and the limitation of the state’s role in the economy, brought home the idea to El Salvador’s business elite that the profound changes ahead required minimizing the diversion of attention and resources by conflict-related factors.

It thus came as no surprise when businessman Alfredo Cristiani, disciple of FUSADES, and member of ARENA, the conservative party formed in the 1980s, won the presidency in 1989 on a political platform of peace and adjustment. A true representative of the new business generation, Cristiani convened meetings with the FMLN immediately upon winning the presidency. Although they were not part of the official negotiating team, representatives of Cristiani’s business group maintained close relations with the government during negotiations.

To a large extent, the Salvadoran private sector’s close relationship with the government and its firm, if informal, grip over the peace agenda explains the absence of more ambitious socioeconomic provisions in the peace agenda. Considered by some as an asset—as it sets verifiable and viable goals—limiting the accords to political and judicial reforms while keeping the socioeconomic part to provisions specifically aimed at the demobilized rebels represented a triumph of the new business elite. With the accords, the private sector got what it wanted: stability at home and new economic rules that enabled them to compete in a new international macroeconomic environment.

The first post-accord years confirmed hopes that the Salvadoran peace agreement was a triumph—at least from a business perspective. Despite increasing crime levels and poverty, Salvadoran business boomed and the economy grew at unprecedented levels. Although much of the growth can be attributed to the remittances of Salvadorans abroad, the words of a company president still ring true: “The peace accords in El Salvador really have been a success. One of the winners has been the private sector. […] No matter how costly the peace, it will be cheaper than war.”

Things did not go as smoothly in Guatemala—as a Guatemalan banker revealed, “We came out of frying pan into the fire.” In fact, Guatemala’s experience with peace has been less than ideal. As in El Salvador, the post-conflict crime rate in Guatemala has risen but unlike in El Salvador, it has not been compensated for with economic performance. In many ways, Guatemala’s lukewarm peace record can be attributed to its private sector’s consistently more distant and ambiguous relationship with peace negotiations. In contrast with the El Salvadoran experience, Guatemalan business exercised less leadership and control over peace negotiations overall. The private sector vetoed key issues during negotiations and implementation of the accords, rather than cooperating with the government to achieve a mutual goal. The resulting relationship between business and peace has contributed to the instability that marks the consolidation of peace in Guatemala.

Different factors explain these differences between the Salvadoran and Guatemalan cases. While both countries underwent economic transformations during the 1980s, this process was less profound in Guatemala—in part due to less U.S. funding for economic remodeling. As a result, the sector in Guatemala most prone to benefit from negotiations gained neither economic nor political predominance, as in El Salvador. This was in addition to the fierce opposition from agrarian interests, which were less weakened than similar interests in El Salvador and thus were more belligerent and effective in vetoing key aspects of the peace process. In fact, opposition from agrarian interests reached the point of filing lawsuits against government negotiators for treason.

There are other, more qualitative differences between the Guatemalan and Salvadoran conflicts that may also explain the disparity in the position of the private sector. The Salvadoran conflict was of shorter duration yet it was more intense than in Guatemala and inflicted great costs to business interests. In Guatemala, in contrast, conflict lingered for decades in the countryside, leading many business people to believe that a negotiated solution was not warranted, as the conflict did not sufficiently interfere with economic activity to represent a true obstacle. As a result, fewer Guatemalan business people were committed to ending conflict in order to secure their livelihood.

A third factor relates to the multiple modifications that the Guatemalan peace policy experienced during the reign of three very different governments over the negotiation process. This differed significantly from the tight control that one business-friendly government exerted over negotiations from beginning to end in El Salvador, and which fostered tensions and distrust in the case of Guatemala.

Another key aspect distinguishes the Guatemalan experience. In contrast with El Salvador, the Guatemalan peace accords include a Socioeconomic Accord stipulating a 50 percent tax increase to finance accord implementation. Intense private sector lobbying tied the increase to an ambitious—and highly unlikely—6% growth rate. Presently, effective private sector resistance to tax increases has required several reschedulings of the accords while Guatemala remains one of the countries with the lowest tax rates in Latin America.

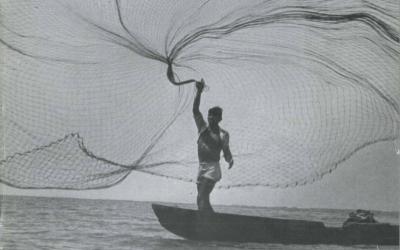

While the Salvadoran peace was largely a business project, and Guatemala’s peace has stuck despite business skepticism and resistance, Colombia offers yet another variation on the business-peace relationship. Here, the last round of peace negotiations failed. However, in contrast with previous attempts, business involvement in negotiations has been on the rise. When negotiations were launched by President Andrés Pastrana, enthusiastic business leaders offered to finance guerrilla members in exchange for a ceasefire. Business representatives participated in meetings with both guerrilla groups—the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) and the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN)—and were part of the government negotiating team.

In addition, the question of private sector involvement in conflict as well as peacebuilding has, more than ever, been on the agenda of both companies and associations in Colombia. In contrast with Central America, more Colombian companies have been involved in peacebuilding and philanthropic activities, notwithstanding the events at the negotiating table. Different business-led peace initiatives at the regional and local levels have spawned projects motivated by the belief that the development of conflict-ridden areas will likely bring peace sooner than official negotiations. While most private companies do not invest their own financial resources, but rather serve as intermediaries of international and public funding, the willingness to invest managerial know-how and time may develop into an important private sector contribution to sub-national development, and possibly, peace.

Different factors explain this business-peace relationship. First, Colombia’s economy underwent a process of diversification earlier than those in Central America. As a result, entrenched rural interests—such as those that led most of the opposition in Central America—are comparatively weaker in Colombia while industrial, financial, commercial, and even an incipient service industry have developed vigorously. In addition, as in pre-negotiation El Salvador, the Colombian conflict is increasingly interfering with economic activity. While many costs associated with conflict were internalized during decades of conflict (as in Guatemala), an increase in conflict intensity during the past years has affected a growing number of sectors of production. This has solidified the notion that “peace is better business,” as one Colombian executive stated.

This is not a consensual view, however. Shortly before talks broke down in Colombia, business associations convened a national, publicly broadcast meeting to pay homage to the Armed Forces. As in Central America, many Colombian business people have been found to support paramilitary activity to protect their companies and property. Especially after last year’s election of Alvaro Uribe as president (his platform was based on the importance of state authority) and in light of abundant U.S. funding through Plan Colombia, many in the private sector maintain hopes that there will be a military solution to the Colombian conflict. This may explain their willingness to pay higher taxes to support the military effort, an important contrast with the Central American countries where the availability of other resources prevented governments from exacting taxes from business.

However, ongoing business support of a get-tough policy is not necessarily guaranteed. Already, business associations have anticipated the possibility of transforming exceptional compulsory and government-issued “war bonds” into permanent taxes in order to gain significant results in the counterinsurgency campaign. Given the diverse nature of Colombia’s conflict and its lucrative funding source—narcotics—this poses a difficult challenge. Already there are signs that President Uribe’s security strategy is not yielding its intended effects: the number of kidnappings is stable while conflict rages on in the countryside and expands to the cities (as most recently witnessed in the bombing of El Nogal, a club closely linked to business interests). Businesses’ reservations are likely to increase as the IMF-sponsored fiscal adjustment program promoted by the government imposes greater strain on companies. Meanwhile, business-led peace initiatives are reaching wider audiences with the compelling message that the solution might not be solely of a military nature.

Eventually, it is likely that the pendulum of peace disposition among Colombia’s private sector will swing back to favor a negotiated solution to conflict. When it does, as suggested by the Salvadoran and Guatemalan cases, it will be crucial to incorporate the private sector in the negotiations. This inclusion will have advantages and disadvantages; as shown by the Salvadoran case, a closed business front may ensure an efficient transition from conflict to peace. However, this closed front can also impose limits on the agenda that may alienate other actors. In contrast, the Guatemalan case suggests that a divided business community, of which important parts are not involved in the process, can also compromise peace stability. Notably, both cases imply that the whole business community need not be in full support of the peace project—only a critical mass of peace stakeholders is required. This mass is growing in Colombia.

Angelika Rettberg earned her Ph.D. at Boston University. She is currently an assistant professor at the Political Science Department at Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia. Research for this article was made possible by grants from Colciencias and from the London School of Economics.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.

Editor’s Letter: Colombia

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American…

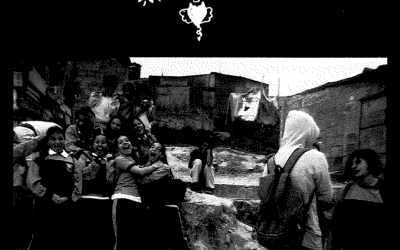

Photoessay: Shooting for Peace

Photoessay: Shooting for PeacePhotographs By The Children of The Shooting For Peace Project As this special issue of Revista highlights, Colombia’s degenerating predicament is a complex one, which needs to be looked at from new perspectives. Disparando Cámaras para la...