Mapping Childhood Malnutrition in Chiapas, Mexico

I love global health. I love to travel, I love learning new languages, and I am passionate about providing health care to underserved populations. Thus, the opportunity to do hands-on pediatric research in rural Mexico this summer sounded perfect. However, what I thought would be a summer of inspiration and enlightenment became an internal struggle to find purpose in my work. I found myself questioning the value of global health, and my role in its mission. Instead of clarity, I often encountered overwhelming ambiguity.

This summer, I worked as a researcher with Compañeros En Salud (CES), a sister organization to Partners in Health. It provides high-quality, primary health care to the Chiapas region—one of Mexico’s poorest and most isolated states. I sought to assess the prevalence of chronic and acute malnutrition in children under five and to make comprehensive maps of this information for future health care interventions. Each week I traveled to a new mountain community with a GPS and measuring tape in hand; I hiked home-to-home weighing and measuring children, interviewing parents about food security, and plotting this data on virtual maps of the region.

Most days were inspirational. The community-members were incredibly warm and open, offering bottomless cups of coffee as they told me their deepest fears about money, food and family. As a second-year medical student, I am still getting used to the privilege that comes with the white coat; I am humbled by the fact that strangers are willing to reveal so much to me about their personal lives and inner reflections—and I hope this humbling feeling never goes away.

I also felt as though I could truly be helpful. Almost half of the children I encountered suffered from chronic malnutrition. Chronic malnutrition may be caused by poor diet, frequent infections and/or poor maternal nutrition while the child is in the womb. If left untreated, children who suffer from chronic malnutrition may not grow to their full potential, mentally or physically. My goal was to intervene during this critical period, to inform parents of their child’s illness and motivate them to act. Many parents seemed to really listen to my nutritional charlas, asking thoughtful questions about their child’s diet. A majority of parents immediately visited the local doctor to engage in more personalized conversations about their child’s health.

But many days I felt hopeless. Many days I didn’t want to go to work, because I knew I’d have to tell twenty more starving mothers that their children were starving, too. And what were the mothers supposed to do with this information? They have no resources; they have no options. I began to question the value of my work. Without reform at the highest level—national and international governments enacting real social change—how can individuals like me hope to improve the health outcomes of these suffering families? I felt myself starting to crumble under an overwhelming feeling of helplessness.

When I spoke to my mentor about these alternating feelings of empowerment and despair, he responded that these were staples of the global health experience. On the one hand, the work is meaningful and often life-changing for patient and physician; on the other hand, global health delivery can feel hopeless when larger social structures work against it. While organizations like CES take both a bottom-up and a top-down approach in an attempt to address health care at the individual and societal level, my mentor still emphasized that as an individual global health practitioner, one needs to hold on to the good days during times of self-doubt. So I am choosing to hold on to the good days—the days full of inspiration and love and hope—and I am excited to use the data collected from this summer to design interventions that will make Chiapas a happier, healthier place. And today, that is good enough motivation for me.

Spring 2016, Volume XV, Number 3

Maggie Cochran is a student at Harvard Medical School. She graduated from Harvard College in 2011 with a major in Psychology. She used her DRCLAS Summer Independent Internship Travel Grant to study childhood malnutrition in Chiapas, Mexico.

Related Articles

The Boy in the Photo

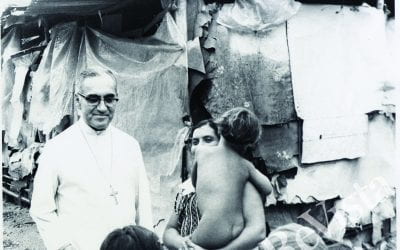

The mangy dogs strolled everywhere along the railroad track. I remembered dogs just like them from the long-ago day in La Chacra in 1979 with Archbishop Óscar Romero, just months before he was killed…

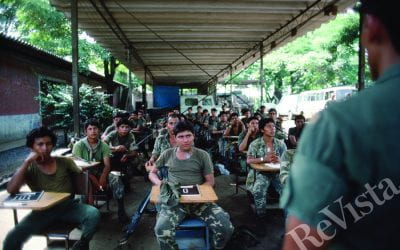

Beyond Polarization in 21st-century El Salvador

My father was a civil engineer who worked for the government during the civil war years. He specialized in roads and had to spend several days a month traveling to remote places in El Salvador. I was 10 in 1986, and I remember my mom asking my dad…

El Salvador: Editor’s Letter

I had forgotten how beautiful El Salvador is. The fragrance of ripening rose apples mixed with the tropical breeze. A mockingbird sang off in the distance. Flowers were everywhere: roses, orchids, sunflowers, bougainvillea and the creamy white izote flower…