The Alchemy of Narrative

Estaba la pájara pinta sentada en el verde limón

Six-year-old Ana peeks out of a keyhole onto her middle-class Bogotá street even though her parents had forbidden her to do so. It is Friday, April 9, 1948, and popular presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán has been assassinated, an event that triggered an era of unprecedented collective fury and intense social violence in Colombia known as La Violencia (1948-66). Ana witnesses the police murder a man in cold blood. She stares at the bludgeoned body and sees a policeman pick up the dead man’s cap, an image that haunts her for the rest of her life.

Even though Ana leads a sheltered life, she is a victim of excessive family control censorship, rape, aggression and even state intimidation. As a young woman she discovers that her best friend, Valeria, a political activist, has been murdered, and later learns that her own boyfriend, Lorenzo, has been imprisoned and tortured. Twenty years after the Bogotazo Ana tells us that 1948 “was the same year in which [she] lost her first tooth and they killed Gaitán, the year she made her First Communion and that her grandfather died from diabetes.” Ana’s intellectual and emotional awakening is bound up with the origins of national history.

Ana is ideally poised to provide an account of the events, but she chose not to write a history or an illuminating testimony. Unlike Joaquín Estrada Monsalve, the country’s Minister of Education during the Bogotazo, who wrote a recollection so that the youth of the country could comprehend “the greatness and miseries of the darkest night of [our] country,” Ana does not write an instructive memoir. Instead, she is the fictional narrator and protagonist of Alba Lucía Ángel’s novel, Estaba la pájara pinta sentada en el verde limón [The Speckled Bird Was Sitting in a Lemon Tree] (1975). The author spurned prevailing realistic conventions and appealed to avant-garde strategies—such as the alternation of multiple perspectives and narrative voices, the use of flashbacks and non-sequential narrative time—to produce a text that is difficult and recalcitrant; that stutters; that does not find its thread; that does not disclose the causes and the meaning of so much violence and terror.

Historians and social analysts of Ana’s generation shared her difficulty in grasping the logic and consequences of La Violencia. In the preface to the landmark study La violencia en Colombia (1962), the authors—Germán Guzmán Campos, Orlando Fals Borda and Eduardo Umaña Luna—wrote that

… [Colombia] lacks the exact notion of what this violence is: neither it has understood it in all its aberrant brutality, nor does it have evidence of its dissolvent effects on the structures, nor its etiology, nor its impact within the social dynamics, nor its meaning as a social phenomenon, much less its importance in the peasantry’s collective psychology(23).

Shared perplexity is surprising, especially if we consider the obvious differences between a modernist novel and a sociological analysis: while social scientists are driven to identify variables with precision to provide a coherent narrative, avant-garde novelists—or at least this one in particular—resist coherence and stage disorientation. The authors of La violencia en Colombia characterized their lack of knowledge as the disorganized proliferation of subjective impressions and the absence of an organizing principle for an analysis of social decomposition. Estaba la pájara pinta…, on the other hand, artfully offers narrative disorder to its readers as its most outstanding formal feature. Its formal governing force is made up of a stream of voices interrupting each other, the absence of chronological linearity and the mundane character of many of the text’s anecdotes. But why would anybody write a narrative about social violence that—instead of seeking coherence—stages disarray? Is there a lesson here for historians, political analysts and other social scientists who want to explore the scene of social devastation?

Readers soon discover that the novel’s style is a thoughtful—if challenging—response to the dislocating effects of intense social violence. Writing bends under the weight of brutality; it demands careful rethinking of the available forms of reporting in order to grasp the eluding logic of destruction. The idea is rehearsed throughout the novel:

Very difficult, I tell you. Because to understand, just like that, so suddenly, so many things, is like wanting to crash through the sound barrier with a bicycle. It’s not a given. One has to remain alert, always looking up at the universe, with one’s skin and eyes wide open, spying the vibration of the colors; the aura of the birds; the movement of the wind; the swaying of the trees; the flow of the water; the dynamism of the clouds; the rotation of the sun, which keeps on burning while your pores dilate and everything in you is as if it were born anew, as if one has finally, finally found the form of all things.… (173).

Ana’s claim is not only that the scenarios of social destruction are highly complex and must be described in depth. She also impugns realism—the belief that reality possesses its own narrative—as the most suitable discursive form for the representation of social experience. “The memories of childhood have no order and no end,” says Ángel, quoting Dylan Thomas, at the beginning of the novel. When coping with intense social conflict, realism might be an ideological straitjacket that obfuscates and impoverishes interpretation. In such cases, narrative order is no more than organized social disorder.

Finding the appropriate form, as the quote implies, is tantamount to comprehending. That is the reason why Ana remained ambivalent about Tina, her childhood friend and only successful storyteller in the novel. On the one hand, she was enthralled by Tina’s inventive talents, her apparently endless imagination and her ability to “[find] words and [let them] fall as they will, not mattering if the public captures them” (79). But although Tina’s stories were quite clever and unexpected, they follow the classical conventions of popular tales, always returning to the word of princes, monsters and fantasies. Ana’s turbulent world, however, required an unyielding form of narration, one that transformed unmalleable truths and exploded traditional discursive forms. Knowledge is not just information, Ana would say if asked: it is information in a certain form. In the case of intense social conflict, conventionally sanctioned forms of reporting might be a hindrance.

Literary forms imbue stories with expectations and values, even if their objective is to defy them. Thus, Estaba la pájara pinta… invokes the traditional Bildungsroman or the coming-of-age story in which Ana, the young sensitive artist, seeks to overcome social obstacles in order to find her place in the world. Ana demonstrates her vocation early on, as she expresses her fascination with words, copying in her diary those with the most beautiful sounds. Language becomes a utopian refuge, a space for mourning, desire, difference and even rebellion. She makes friends who, like Valeria, also a writer, become mentors and models, and the text suggests at several points that what we read is Ana’s own attempt to give meaning to her life. The discursive frame usually invoked by this type of narrative makes the elements available with which the story constructs a moral and social universe. That the novel resists such conventions—instead of fulfilling its expectations—shatters all the more effectively our readerly expectations.

In Ana’s account there is no knowledgeable authoritative subject to guarantee growth and learning; no one can uncover the structuring logic behind social chaos or organize traumatic memories and convert them in a coherent history of progress and development. Not that the narrative does not gesture in that direction. It draws from memoirs and other documents providing composed and conclusive interpretation of the tragedy. These are historical documents authored by the political elite, such as Doña Bertha, President Mariano Ospina Pérez’s wife, and the already mentioned Minister Estrada Monsalve. Their interpretation hinges on the view of Bogotá as South America’s “Atenas” or Athens, as it was proudly hailed, the aristocratic seat of a refined and cultured civic tradition. “The destruction of the most civic-minded, most spiritual and intelligent city in all of Latin America,” writes Monsalve, “caused great bitterness.” In this narrative, the Bogotazo and its aftermath were barbaric interruptions by morally debased people lacking in education and civility. These accounts lamented the invasion and violent displacement of the cultured city by the chusma, the dregs of society, and showed a topsy-turvy world in which social hierarchies were suspended and both moral and political authority ceased to exist. Authorial voices appear as obstacles to understanding.

In contrast, the text inscribes vivid accounts of non-elite first-hand witnesses, such as Sabina (who works in Ana’s house), Don Anselmo, a displaced peasant who lost all his family, and Flaco Bejarano, or the story of Flower, the striptease dancer shot to death during the Bogotazo. Their accounts ridicule elite composure, but they do not converge in an authoritative interpretation. They permeate the narrative with moral indignation and contribute to the sensation of uncontrollable chaos and despair. Upon learning of Gaitán’s assassination one of his sympathizers evinces a shattered sense of hope:

…I began to shout furiously, like everyone else…and I sobbed, crying out for my God. It was as if they had killed my mother and my father and all of my family altogether, such anger, such impotence, brother. Here is what has to be done: to go all out; there’s no other remedy.

Telling and listening to stories—a multitude of diverse and often contradictory stories—is related to comprehending. Only when listening to those we hastily label “victims” does the possibility of true understanding emerge. These testimonies not only provide multiple points of view to satisfy our intellectual curiosity. Most importantly, they allow for mourning, the process of subjective reconstitution and the re-elaboration of a collective sense of belonging. Empathy, the relational connection between the inquirer and the subject whose experience constitutes the field of investigation, can thus take place and be part of comprehending.

The novel alternates between the proliferation of testimonies and the reluctance to inform; between an impulse to give account and the disinclination or incompetence to speak. As a child, Ana often found herself with a “horrible urge to cry and did not know why.” Don Anselmo survived possessed by the kind of extreme vivid images that characterizes traumatic experiences. Exhausted from those images, Don Anselmo

… completed the porridge and remained silent, thinking of all the bodies floating in the rivers. Of the elderly and children who had been shot. The old man did not hear her. … Ana saw Don Anselmo with his arms folded across his chest, praying on his knees while tears were hanging, cradled in his wrinkles.

Our intellectual and creative pursuits are located between these two impulses: telling or mournful reconstitution and withholding or melancholic remembrance. Ana’s implied argument is that interpretations might further the work of mourning or constitute a disavowal of the other’s pain. In all cases, our lack of attention and imagination in the reception and processing of testimonies denies pain and constitutes a double act of violence. Overall, it inevitably becomes a generator of new violence.

Anselmo’s scene elaborates what might be the most serious challenge to researchers of social conflict: the intransitive character of emotional pain, the fact that I can feel my pain but cannot show it or point it to someone else. Furthermore, by isolating Anselmo’s suffering, the scene highlights the absence of technical languages that can communicate its nature, that can alert us to its insidious effects, the modes in which it works in memory and construes daily life. But pain is also a beckoning, a desperate call soliciting recognition, and testimony is our precarious but precious mode for apprehending it. It is the vehicle through which learning about the pain of others is possible. To receive somebody’s testimony, that is, to be a witness to his or her suffering, demands we understand with intellect and emotions. Testimonies make evident how people absorb painful memories and root them into their everyday, use them to their advantage, or simply evade them by coexisting with them. Anselmo’s testimony bears their imprint: the ways he suffers, perceives, persists and resists such violence; remembers and mourns his losses. Knowledge of what happened —what happened to Don Anselmo and to others, but also the role others played in what happened to him—silently structures social relations. His knowledge is poisonous, but his testimony affirms the will to live.

Clearly, silences are not lacunae of information. Most frequently they inscribe a resistance to yielding; they insist on the difficulty of comprehending and the labor of recognition; they challenge and return to the unreason of suffering; they set up interpretative limits to the voraciousness of scientific inquiry. Most evidently, they speak of the incidence of the violent past in the present. But they never represent a renunciation of the telling. The novel might be teeming with silences, but they are all contained in the act of telling; and the telling inscribes silences as part of the story.

Listening to testimony requires imagination. If the language of science remains impervious before the scene of social devastation, those who speak scientifically will have to borrow, steal, concoct words, insinuate and modulate in order to break up the silence. Like Ana. After all, it is such exercise of imagination that makes empathy possible, the attribute that knowledge lacks in order to arrive at true comprehension. Telling and listening, therefore, are integral parts of understanding. They are related to three important and clearly differentiated functions: they name the violences; they are the means by which victims re-establish a relation with others; and they make possible mourning.

It is not surprising that such knowledge is deemed dangerous. Ana is forbidden to get near the door during the Bogotazo; she is not allowed to listen to the stories about the violence at the family farm or to read newspapers during the student massacres. Her mother scolds her when Ana begins to express interest in books. As part of a middle-class respected family she is kept from seeing, hearing and knowing—from becoming a witness. The novel reproduces—and parodies—this need for control: an image of President General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla’s ban on any report or editorial about the student massacres of June 8 and 9, 1954, appears on the front page of El Tiempo, the country’s main opposition newspaper. The repeated figuration of writing as transgression, such as Lorenzo’s letters from jail or Valeria’s writing and her death at the hands of the police, suggests that narrating history is dangerous, even fatal.

Estaba la pájara pinta … is a meditation about apprehending, comprehending and representing difficult, poisonous knowledge in the midst of social conflict. Its starting point is that Ana’s social experience—as the experience of those who lived through La Violencia—demands a type of inquiry and reporting that takes into account its intense nature. Eschewing received notions of fiction and history, its stylistic choices and notorious difficulty embody this meditation for the reader. It insists on apprehending the way memory works and thus seeks to transform information into testimony, while nameless victims become human subjects. The novel seeks to give testimony on the devastation that took place in the country during the ten years between Gaitán’s assassination and the bipartisan agreement that put an end to La Violencia.

All of this makes the novel relevant for social researchers today, as the country moves towards a peace agreement and faces massive demobilizations, truth commissions and the reparation of victims. Much as what happened in the aftermath of La Violencia, when Liberals and Conservatives, the two parties responsible for instigating fratricidal violence, reached a peace agreement in 1957, contemporary political figures stake out their claims on the past and saturate public discourse with their view of the conflict. Most of the country greeted the cessation of the conflict, but grew weary of a National Front that harked back to the civilist myth of the South American Athens and shut off most non-elite from political dialogue. The following years saw the birth of the two main guerrilla groups, FARC and ELN, and the sowing of the seed of the conflict that still grips the country today.

Contemporary researchers might want to look back at the creative ways in which the country responded to La Violencia. Like Estaba la pájara pinta…, other works, such as Arturo Alape’s El Bogotazo (1983) and Alfredo Molano’s Los años del tropel (1985)— sought to testify and record the silences and nightmares of the Anselmos, Flowers, Sabinas, and thousands more, who remain at the margin of history. Today, once again, arts, literature and social sciences are called forth to play an important role in the recovery of languages and memories of pain, true laboratories to construct to conviviality of the future, one in which death is no longer the structuring center of social life. We cannot renounce such an urgent task.

Spring 2013, Volume XIII, Number 1

Francisco Ortega was a Visiting Scholar and Teaching Assistant at Harvard’s Department of Romance Languages and Literatures from 1995 to 1999 and one of the founders of the Colombian Colloquium at Harvard in 1997. He is an Associate Professor of History at the National University of Colombia in Bogotá.

Related Articles

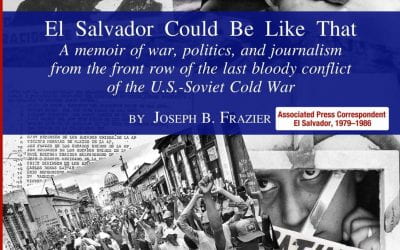

El Salvador Could Be Like That: A Memoir of War, Politics, and Journalism from the Front Row of the Last Bloody Conflict of the U.S.-Soviet Cold War

“There are no just wars. There are only just causes.” I was sitting in the modest home of a former FMLN guerrilla woman in a rural village in the northeastern corner of El Salvador. It was 2001, and I was nearing the end of my second year-long stint in this small Central American nation, interviewing more than 200 Salvadorans, mostly from rural areas, about their experiences during the civil conflict of the 1980s. …

First Take: Memories and Their Consequences

I visited the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos in Santiago, Chile, two years ago. It was a heart-rending experience. To enter the museum, I moved through a stark and subterranean passage and found myself in a somber space of transition. There, a wall of photographs transported me back in time—long ago in a messy graduate student lounge in Cambridge, Massachusetts, four of us stood in shock …

An Exploration of the Mexican Health Care System

The recent creation of Seguro Popular—a governmental program granting basic health services to millions of Mexicans previously uninsured—has newly enabled thousands of Mexican women afflicted with breast cancer to access treatment. With the growing prevalence of breast cancer survivors, the question now arises of how best to maintain their health and address their needs. …