Mexican Women

Historical Perspectives

When I began my research on 19th century Mexico City women 20 years ago, it did not take me long to realize that what Mexican women were supposed to do, and what they actually did were sometimes quite different.

Mexican women in the past were supposedly sweet but passive and powerless human beings, whose lives revolved around family and home, and who were completely subordinated to men. This, in fact, was the cultural ideal. A famous Spanish proverb declares, “El hombre en la calle, la mujer en la casa,” that is, “men in the street and women at home”.

Although a huge gap almost always exists between the “supposed to’s” and actual behavior all around the world, we have too often believed that in Latin America things really were that way. That Latin America was more traditional, that the separation of male and female roles was indeed greater there.

But this is not entirely accurate, not even for the most “traditional” of times, the early 19th century.

One day early in my research, I was sitting in the archives sifting through the dusty, worm-eaten papers. As I examined the documents–which is what I most love to do in the whole world because they are always full of such amazing things–I stumbled across a lovely court case. In the case, a gentleman testified that his sister-in-law, Doñ María Antonia Reyna “has excellent qualities…and is much devoted to her home”–exactly the way women were supposed to be. But then he added “virtues difficult to find among women in these times.” So, according to this gentleman, she was the exception in 1816. Thirty years later, statesman-writer Manuel Payno complained that women shunned their destiny by avoiding marriage and motherhood, and termed rampant spinsterhood the “cancer of the very fabric of morality.”

What’s going on here? I would like to paint a picture of Mexican women in the “traditional” 19th century that is at odds with our standard stereotypes. In the process, I would like to challenge two deep-seated assumptions many of us have–one about progress in history, and another about Latin America and the United States.

The first assumption, about history, is that things were worse in the past, and had steadily gotten better. It turns out that this trend is not always true. Much of what we consider traditional is in fact relatively new in historical terms. It was more common for women to marry and have lots of children and to live out their lives in a male-headed family in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s than a hundred years earlier. It does not take long, however, before some patterns became associated with tradition, and we assume that they always have been around because we see it was that way in our parents’ and grandparents’ times. The “traditional” patterns of Mexican women’s lives are more often mid-20th-century patterns than 19th-century ones. So in a sense things deteriorated, or at least there has been no straight path from tradition to modernity.

The second assumption I want to challenge is that the situation of women was worse in Mexico than in the United States, then and now, that we are and always have been more modern and better than undeveloped, Hispanic Mexico. However, a feminist movement did not develop as fully in Mexico precisely because Mexican women enjoyed certain legal and social advantages U.S. women did not.

Demography, as well as women’s work and legal status, gives us some clear indications about the huge gap between the “supposed tos” and the reality of the 19th century woman.

Everyone knows that the traditional Mexican family was headed by the all-powerful patriarch. Wrong. In 1811, one third of all households in Mexico City were in fact headed by women. Adult single women were a normal part of everyday urban life in the 19th century–far more so than in the 20th, when spinsterhood became much rarer. For a variety of reasons, such as a surplus of women in Mexican cities and a high death rate that killed off husbands, many 19th-century women were not directly subject to men.

The women in charge of households were usually widows, occasionally spinsters and abandoned wives. I found this pattern in two Mexico City censuses; other historians have now found large numbers of female household heads in nearly every Latin American city in the 18th and 19th centuries. In fact, marriage was not nearly as widespread as we have assumed: there were lots of bachelors and spinsters. One out of every six Mexico City women never married in the early 19th century, and was listed in census at the age of 45, 50, or 55 as single and childless. And although many couples lived in consensual unions not legalized by Church or State, if they had children, they listed themselves as “widowed” after separation, rather than “single.” Despite the oft repeated assertion that women had but two career options, marriage or convent, this was simply not true by the 19th century, when very few women entered convents.

Widowhood was even more common than spinsterhood. In fact, one-third of all adult women in the Mexico City census of 1811 were listed as widows. Whether they had ever been legally married or not, they shared the experience of being on their own, free from direct male control. These women had full legal rights: they could work without anyone’s permission, sign contracts, buy and sell at will–and they did all these things. However, they earned considerably less than men, which meant that unless they inherited property, widows and spinsters saw a drop in their standard of living when their husbands or fathers died. So the feminization of poverty we recently discovered is nothing new–it is centuries old.

Nevertheless, Mexico’s legal system gave women more protection and rights than they had in the U.S. or England at the time, especially in the area of property rights. Four-fifths of the estate had to be divided equally among all the children; daughters received the same portions as their brothers. A man could not leave his wife penniless either, for she was automatically entitled to half the community property. Widows also got their dowries back–that is, the property that had come from her parents when she married. During the marriage, a husband controlled both the community property and the dowry, but he did not ever own the dowry: the wife did. The law tried to preserve the dowry, so that it would still be there if she became a widow. Widows were not subject to male guardianship, not by fathers, or brothers, or sons.

In 19th century Mexico City, one-third of all Mexico City children were brought up by their mothers in female-headed households without a strong father figure. Given the relatively short life expectancies of the time, many of these children did not know their grandparents either. Indeed, our image of the extended household where several generations lived together under one roof applies to very few families. The nuclear, not extended, household, was the rule. This contrasts with mid-20th century Mexico, where higher marriage rates and greater longevity meant most women lived out their lives as daughters, then wives subject to male control.

Other patterns that we think of as new, women’s work and migration, are also very old. During the 18th and 19th century, Mexicans faced a terrible crisis in the countryside; many women traveled on their own to the cities to find work, since men could often find alternative jobs in mines or on rural estates. In 1811, women made up a third of the identified labor force: the same proportion of female employment as in the 1960s. Many women were not included in the 1811 census, such as wives and daughters who helped in a family shop or women who worked as prostitutes. Although there was a strong view that women should devote themselves to domesticity and that it was a misfortune for women to work, these ideals were not attainable for perhaps half the population. Consequently, the ideal is not a good indicator of what people did.

Clearly, some of our deep-seated stereotypes about Mexican women continue to persist. They persist because we look only at the literature with its fantasized ideal of patriarchy rather than at hard data such as censuses. They persist because we often fail to distinguish among women of different social backgrounds, and because we assume that progress is a continuum with the 19th century flowing ahead into the mid-20th century and to modern-day Mexico. Finally, we all too often draw on our own sense of superiority. Unfortunately, the Black Legend of Latin American backwardness and inferiority is very much well and alive, and still providing the lenses through which we view Latin America–often, as I hope I’ve convinced you, leading us astray.

Silvia Marina Arrom is the president of the Boston Area Consortium on Latin America (BACLA), director of the Latin American Studies program at Brandeis University, and a DRCLAS Affiliate.

Related Articles

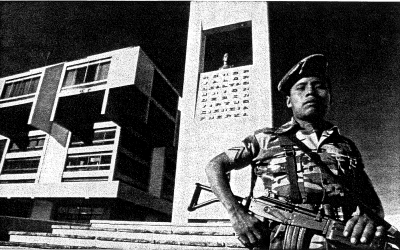

Interviewing Military Officers

We drove up into the residential hills of Villa Hermosa, overlooking the city of Guatemala, searching for the house amongst the many white-stucco, high-walled mansions. I asked the taxi-driver …

Disobedient Autobiographies of Las Desobedientes

From the quasi mythical conquista-age Malinche to contemporary women such as Rigoberta Menchú and Rosario Castellanos, Las Desobedientes restitutes the women of Latin American history …

Delivering the Data

Marta was 18, living at home in El Salvador, when she dated a man who raped her. She told her father about the rape, and he responded by threatening to kill her for damaging the family’s …