Mexico’s National Museum of Film

Filmmaking and Identity

Mexico has a long history of filmmaking, from the silent era to the present, with some particularly prolific periods that have been stimulated by state sponsorship and international recognition. Appreciation of the results began in the 1940s, when Mexican films won prizes at European festivals such as Cannes, has continued more recently with the success of directors such as Alfonso Cuarón (Y tu mamá también, 2001– And Your Mother, Too), Alejandro González Iñárritu (Amores perros, 2000- Love’s a Bitch; Babel, 2006) y Guillermo del Toro (El laberinto del fauno, 2006– Pan’s Labyrinth). The National Museum of Cinema seeks to broaden Mexico’s collective knowledge about its national film history, but first I’d like to provide a little bit of it here.

During the silent period, cinema served as both entertainment and a source of information through fiction features, very much influenced by European and American films, and through documentaries that registered the final phase of Porfirio Díaz’s dictatorship (1876-1910) and the avatars of the Revolution (1910-17). In the 1920s, film production was not so abundant in part because the newly formed state focused on sponsoring other projects such as public education and mural art. It was not until the mid- 1930s that the post-revolutionary state invested in cinema on a large scale, which led to the formation of a film industry that in the 1940s dominated the market of the Spanish-speaking world (Latin America, Spain and the United States). This period, known as the Golden Age (1935-55), saw the emergence of new genres, directors with distinctive styles and a local star system that helped to assure a massive audience. Characterized by the predominance of a nationalist discourse and a melodramatic narrative, Golden Age cinema gained international recognition particularly through the success of director Emilio Fernández and his cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa.

In the 1960s, a new generation of filmmakers and film critics began to reject the 1940s popular cinema. Their attempts to form a new film culture, along with state funding in the early 1970s, contributed to the development of a kind of auteur cinema led by directors like Felipe Cazals and Arturo Ripstein. In the early 1990s, Mexico’s cultural scene came to be refreshed by a new corpus of films produced by younger directors, which would come to be known, both locally and abroad, as the New Mexican Cinema. While several of these directors have continued to consolidate their careers, with some of them now settled in the international arena, in recent years other new filmmakers have managed to produce their first feature films, despite the financial difficulties aggravated by Hollywood’s supremacy in the country’s movie theatres, and to a large extent thanks to the support provided by local annual festivals such as those in Guadalajara and Morelia.

Unlike the auteur cinema produced from the 1960s to the present, which has been viewed and praised mainly by the middle classes, the more popular, industrial and melodramatic cinema (Golden Age films and successful genres of subsequent decades such as wrestler and fichera films) is very much cherished by a large part of Mexico’s population. Love of these older films has been fuelled by the state and by media companies that have promoted this film heritage through retrospectives, commercial DVD editions and constant TV reruns. In particular, Golden Age cinema has been widely celebrated by official discourse and the mass media as a key component of the nation’s cultural heritage, for instance through homages dedicated to directors and stars.

Mexico’s long tradition of preserving its film heritage is maintained at present by institutions like Cineteca Nacional (Education Ministry) and the Filmoteca UNAM (National Autonomous University), film studios (Estudios Churubusco) and private collectors; all of them have preserved not only the films themselves but also a wide range of still images, sound material and all sorts of objects related to cinematographic production.

Such preservation work has led to the creation of the National Museum of Cinema, a project sponsored by the Mexican Institute of Cinematography (IMCINE), the official entity in charge of promoting the development of the country’s cinematographic activities. President Felipe Calderón announced the creation of the museum in 2008 during the celebrations of the centennial of the birth of the cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa. The document outlining the project highlights the cultural and educational function assigned to the museum, stating that it will be “a dynamic and interactive space that will illustrate the history of our cinema and the contributions made by Mexican cinema’s images and filmmakers to both our culture and our collective imaginings”. The document also envisages that the museum will take part in the reconfiguration of the national identity, stating that the project aims “to draw the new generations to the cultural referents of our cinema in the process of constructing our national identity for the 21st century”.

The initial stage of the project has involved the formation of a multidisciplinary working group that includes film scholars, collectors, museographers, scriptwriters, architects and visual artists. This group is currently working on the museum’s inaugural exhibition, entitled Cinema and the Mexican Revolution, which will open in the second half of 2010 at the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso during the commemoration of the centenary of the beginning of the Revolution. Conceived as the official “letter of presentation” of the museum, the exhibition will explore how cinema, both national and foreign, documentary and fiction, has represented the Mexican Revolution from the outbreak of that war to the present day.

Housed in nine rooms, the exhibition will treat the following themes: the sociopolitical and cultural context of pre-revolutionary Mexico; the documentaries produced during the Revolution; the representation of the revolutionary leaders (caudillos) in fiction films; the genealogy of the representation of the Revolution in Mexico’s visual culture in the 1920s and 1930s; the construction of natural and artificial spaces in the mise-en-scène of the films; the representation of the physical and social mobilizations caused by the civil war; the characterization of violence and death during the war; the construction of gender identities in fiction films; and finally, the representation of the Revolution in Hollywood and European cinema. The design of these rooms will be based on both the research carried out by film historians and the proposals made by museographers and artists. In addition, there will be outdoor public exhibitions that will include installations and activities such as film screenings, a collective book with research articles that will be based on the exhibition; and a television series produced by TV UNAM using some of the research findings.

The creation of this museum is inscribed within a long tradition of administrating cultural heritage that was implemented in Mexico from the beginning of the post-revolutionary period. Given the nationalist orientation of its post-revolutionary policy, Mexico has invested a great deal in both preserving its cultural heritage and integrating it into an extensive system of museums, more than any other country in Latin America. As UAM anthropology professor Néstor García Canclini indicates in Culturas híbridas. Estrategias para entrar y salir de la modernidad (México: Grijalbo, 1990), museums have constituted the scene for the classification and assessment of cultural goods in Mexico along with schooling and the mass media.

Since the heritage to be exhibited is film, the National Museum of Cinema could prove to be at once advantageous and sensitive, as it will be maneuvering a corpus of cultural goods that hold a special place in the collective imagination. In this sense, it will be interesting to see how the museum addresses the visitor as a citizen in relation to his/her country’s history of filmmaking. In “Muralism and the People: Culture, Popular Citizenship, and Government in Post-Revolutionary Mexico” (The Communication Review, 5:7-38, 2002.), Dartmouth College art history professor Mary K. Coffey describes the museum visitor as a “‘citizen-addressee’ who is hailed by the museum as a subject and offered ‘a position in history and a relationship to that history’ ”. In addition to noting this function, we will also witness to what extent the museum mobilizes a discourse regarding its potential contribution to a process of reconfiguring the national identity, as the document presenting the project suggests.

In displaying the history of the film representation of the Revolution, the exhibition will allow the viewer to see how this representation has changed over time, in accordance with discursive formations and the political necessities of the various historical periods. The exhibition will carry out a conceptual and spatial organization of film materials that will guide, in one way or another, the interpretations of the visitor/citizen about cinema’s construction of the Revolution. In the context of Coffey’s analysis, this is related to the fact that the meaning of any visual culture is always contingent upon contextualization; an idea that can be developed further through the following questions: where is the piece of visual culture located? What are the rituals governing interpretation in that site? How is it framed or positioned?

Through this exhibition and subsequent ones, the National Museum of Cinema will provide novel and unique ways of displaying and socializing Mexico’s film culture. This will allow the public to reflect upon the significance of this crucial aspect of the country’s cultural history and, consequently, also on the role of audiovisual culture in the construction of collective imaginings and identities.

Fall 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

Claudia Arroyo Quiroz holds a doctorate in Latin American Studies from the Birkbeck College (University of London) and is a research professor at the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Cuajimalpa in Mexico City. Her research has focused on Mexico’s cultural history of 19th and 20th centuries; she has published articles on nationalist and identity discourses in Mexican literature and film.

Related Articles

Coconut Milk in Coca Cola Bottles

Common knowledge has it that virtually any movie, once removed from its original cultural context of production and reception, might be either misunderstood and misperceived or re-interpreted and re-signified. Likewise, we may agree that national cinemas seek to define, challenge….

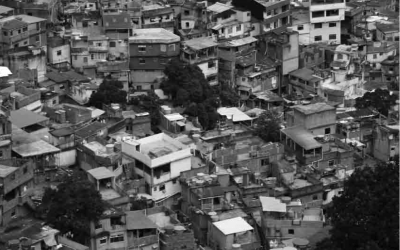

Neither the Sertão or the Favela

To frame the poetics of the ordinary in terms of subtlety and delicateness is to propose an antidote both for cynicism and for what I call Neo-Naturalism. Its appearance, at least in Brazilian cinema and literature, has been clearly identified, ranging from peripheral subjects…

Brazilian Cinema Now

Snow falling in the city of São Paulo, in southern Brazil? Taking a helicopter in São Paulo then arriving a few moments later in the deep wilderness of the Amazon jungle, half a continent further away to the north? Then meeting a white Asian tiger in the heart of the Amazon forest?…