Migration

The Hidden Face of Globalization

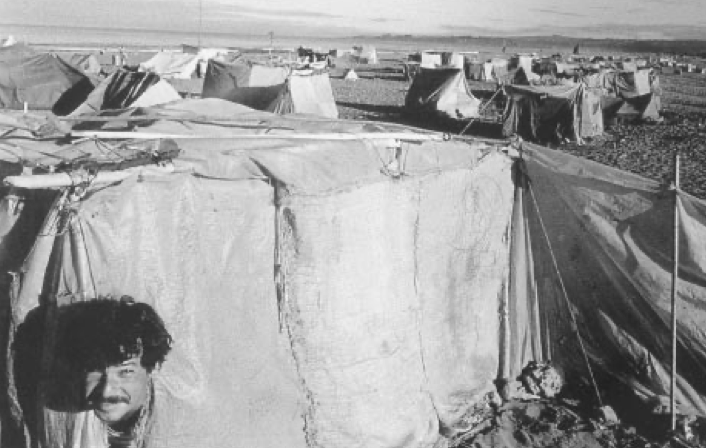

Playa Grande, Cartagena, 1988

In the last decade, citizens from Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Argentina and Cuba have flocked to Chile. They migrated to Chile with expectations based on the stability of the economic model, university system, health services and the structure of the Chilean labor market. Although this migration has not been a largescale phenomenon, the presence of foreigners has generated some instances of discrimination that have been denounced by organizations of migrants in neighboring countries: exclusion based on nationality, mistreatment, employment in underpaid jobs, and other excluding actions.

In the 1990s, the economic, political and financial situation of the country differed greatly from the shaky democracies and economies of other countries in Latin America. As a result, many of these Latin American nationals expect to find in Chile the right destination for finding a job and improving the living conditions of their families. This was the beginning of an important migration from Peru and Ecuador, but this time on an individual and job-oriented basis that has resulted in around 60,000 migrants in the last three years. The countries of origin have reacted by establishing high migration rates, rises in the cost of passports and certification to travel abroad. Migration is not a new phenomenon in Chile, but these new immigrants are finding a completely different context from previous migratory flows. Like most Latin American countries, the Chilean society has its roots in migration. The first wave in the 19th century resulted from specific national policies to promote European migration in order to populate and develop the local economies in remote places. German families settled in the south, in regions inhabited by mapuches. English, Yugoslavian and French families immigrated to Patagonia. As migration grew stronger in the 20th century, Spanish, Italian and English families settled in Chile’s Central Region.

Most of Chile’s first waves of immigrants came from groups affected by Europe’s critical situation at the end of the 19th century and the two World Wars. European migration was promoted and encouraged through the allocation of land or some benefits stipulated by specific laws. In those days, the basic assumption was to favor European citizens because they were better at developing a work ethic as pioneers in areas not inhabited by Chilean citizens. The truth is that the German nationals were taken to areas that had recently been under dispute with the mapuches, and the English subjects and Yugoslav citizens were taken to areas that required a population that could guarantee territorial control in Patagonia. At the same time, the migratory flow of Chilean citizens of the Central Region to the northern territories that resulted from the war with Peru and Bolivia was encouraged.

In our more recent history, in the 1970s and 1980s, Chile was characterized for being a banishing country, mainly for reasons associated with political and economic events. General Augusto Pinochet’s military regime and the early-1980s economic recession led to the migration abroad of at least 500,000 Chilean citizens.

In the late 1980s, as a result of the highest macroeconomic growth in Latin America, the existence of a democratic system and the improved level of expectations about living standards, some 80,000 Chileans living abroad returned home—a phenomenon known as the “retorno.” To favor this migration, special laws were passed to establish settling privileges and benefits, special franchises to bring duty-free goods into the country and special loans. The government created an official office to provide assistance and advice to those who were returning to Chile.

The situation of today’s immigrants contrasts with not only previous European immigrants, who easily integrated into the cultural, economic and social elite, but the structures provided for the “retorno.” Policies must now be formulated in Chile to encourage the acceptance of diversity and non-discrimination and the construction of values and practices for integration. The migratory variable must be increasingly taken into account in the design of the economic, social and cultural model of any country aspiring to be modern—and that is Chile’s highest aspiration, to be an integral part of the globalized world.

Migration is one of the most important phenomena of globalization. Integration is only possible among people. In other words, we are interested in globalization at a human scale.

International law provides no definition of migration or migrant; it is getting increasingly difficult to distinguish between those who emigrate from a country for political, social or economic reasons and those who emigrate with the expectation of improving their living standards. However, it is possible to confirm that those who have no rights in another country are in a situation of increasing vulnerability and lack of protection. Very often they are stigmatized by other people as “illegal,” when they are actually human beings only lacking a politico-administrative status.

In the Americas, the vulnerability of immigrants shows the increasing gap between the development of regional policies to promote the flow of goods and services and a policy of restrictions to the migration of people. It is interesting to observe that every day there is more and more freedom for the traffic of apples, minerals, electric appliances and capital investment, while international restrictions on the flow of individuals and their families grow. This evidence clearly requires a deeper reflection about the need to consolidate a “globalization of citizens” as the basis for the construction of a global economy.

These considerations trigger the daily questioning of the actual validity of the human rights of around 13 million migrants in our continent, as they move from one country to another mainly for economic reasons. Attention has focused on Mexico, El Salvador, Haiti, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Bolivia, and more recently, Argentina. These facts pose one of the most interesting challenges of our time, not always met at Economic or Regional Integration Forums: the need to establish a status of Inter-American Citizenship. Every person has human rights in view of their condition as a human being, and discrimination based on nationality cannot be tolerated. Every person has a natural citizenship the bases of which are the International Human Rights Treaties. It is the duty of our countries to set up the conditions for migrants to enjoy, exercise and demand such citizenship.

This need assumes the joint action of the countries of the region. Policies to protect the rights of workers or migrant families in the host country will not be effective unless they are accompanied by policies in the country of origin. It is this increasing and very often “hidden” demand that will make it necessary for our countries to adopt specific and definite agreements that should be compulsory, mandatory and widespread in the Americas, a continent that is growing and defining its character as a result of migration.

THE VALUES OF TOLERANCE AND NON DISCRIMINATION

In Chile, public policies have established a difference that favors the migration of “white” Europeans by regulating migration from neighboring countries. It may be of interest to observe whether the Chilean society has discriminating or excluding features, and whether differentiation between individuals is the result of a discriminating social pattern.

According to IDEAS Foundation statistics, Chilean society is clearly discriminatory, but through “passive” differentiation. In terms of gender, the statistics are clear: there is a clear inequality in the access to political and even economic decision-making posts for women. Women’s share of seats in the National Congress is an average 9.5%; their share in political parties is 26.2%, all this in a country in which the percentage of validly returned votes of women exceeds that of men (Seewww.mujereschile.cl). Only 39.5% of women access Higher Education. On average, women get 50% less pay than a man for the same job (See www.ideas.cl).

As for sexual diversity, 46% of the Chilean population does not accept a gay or lesbian teacher for their children. These figures are only a sample of a society that discriminates in its cultural and social patterns.

This discrimination is based on one single traditional and classic cultural pattern of family parental model, which is male-oriented, with a Catholic background, basically Spanish in origin and “white,” with little tolerance for sexual, religious and even political diversity. The cultural situation in Latin America is similar.

The questioning arises when Chile is presented as an economically modern country. The question is whether this modernity is only limited to criteria for the economic management of large amounts of public spending money, or whether it is possible to build an integrating, tolerant and diverse modernity based on human rights.

To build from these rights, development should be consistent with the social, cultural and economic conditions. The recent experiences in Bolivia, Venezuela and Argentina show that the implementation of economic plans based on purely economic criteria imply the risk of social crisis and exclusion.

To sustain the Chile’s growth model, social and cultural integration policies must be implemented and the participation of citizens at all levels encouraged. Other necessary goals include the promotion of the culture of public interest, recognition of collective rights, improvement of low-income sectors’ access to justice, generation of a culture of respect for sexual and reproductive rights, encouragement of the use of public spaces, promotion of micropractices of tolerance and the opening up towards a society that includes cyber-rights or the right to transparency and information. In short, a solid foundation must be laid to enable the creation of a culture of tolerance and diversity.

The academic world must take up this challenge through research, high-level events and proposals in the field of migration and fundamental rights. It must continuously test the coherence of equality in each context and laythe foundations for experience-based training in tolerance and even in the process of mutual acceptance.

An important issue is how to involve the corporate world in this process. Economic integration agreements have a high impact on the economic, social and cultural rights of both the associated countries and their populations. There has been a shift from the person who demands rights from the State to the person who increasingly demands more rights from companies. It is in this space that the question arises about the role of economic actors as promoters of human rights for one and all.

“Chile, our promised land”

THE STATUS OF CHILEANS ABROAD

One of the debts still to be settled and one of the most serious contradictions of the migration policy of the country is the status of Chilean migrants in (and from) other countries. Because of issues of money, employment or resettlement, almost one million Chilean nationals do not have full civil and political rights. Groups of Chileans have repeatedly expressed their willingness to take part in the country’s economic, social and cultural life. Coalición governments have designed plans for their integration and social insertion, but the actual materialization of their political rights is still pending.

Despite the fact that in the early 1990s a specific policy was designed for the return of Chileans to the country, including tax exemptions and duty free rights, there is a legal, political and social scenario that in practice prevents these thousands of Chileans from resettling in the country. There are no international treaties that guarantee the exchange of pension or welfare funds, double taxation that works properly, trans-country border information flow and other aspects that must be regulated so as to allow for the full exercise of citizenship. If the country aspires to true globalization, it should acknowledge the rights of Chileans at all levels, beyond politico-electoral or party-political considerations.

In signing economic integration treaties with Canada, Mexico, the United States, the European Union, Korea, Central America, China and Japan, Chile should consider essential such issues as migration, protection of human rights of migrant workers and their families, as well as the definition of policies for the protection of the economic, social and cultural rights of nationals in the associated countries.

It will be thought provoking to get a glimpse of Chile’s capability to develop leadership in social and cultural issues, migration being one of them. The definition of a modern country assumes the consolidation of non-excluding citizenship.

Spring 2004, Volume III, Number 3

Diego Carrasco is director of the Observatorio Interamericano de Migraciones, FORJA — PIDHDD, as well as legal counsel and consultant for the foundation IDEAS. He is a lecturer at Universidad Diego Portales and Universidad de las Americas. He can be reached at carrascodiego@vtr.net.

Related Articles

Poverty or Potential?

Teresa stops me three blocks from Nueva Imperial’s main plaza on a quiet Wednesday morning, eager to chat. She is wearing a light blue sweater and a matching blue headband glowing slightly against her dark black hair.

Editor’s Letter: Chile

I was hesitant to do an issue on Chile when I had other topics broader and richer in content. Although in a way Chile seems like an obvious choice because of the DRCLAS Regional office there, I felt there were other priorities in terms of substance.

Three Students, Three Experiences

I was extremely impressed with how successful the Chilean health system has been in improving the health of its citizens despite its limited resources. Its success, however, in many…