Nicaragua: Images of Division

A woman points to bullet holes inside Jesús de la Divina Misericordia church in Managua. Witnesses said the gunfire was unleashed by pro-gov’t paramilitaries and police against students taking shelter there.

Elsa Valle Montenegro, 19, was inside a friend’s home following an anti-government demonstration in Managua when police burst in. Members of Consejos del Poder Ciudadano, a system of neighborhood government informants, saw Valle enter the home after taking part in a march. Valle was one of six university students arrested near Universidad Politécnica de Nicaragua (Upoli) June 14, 2018, accused of illegal possession of weapons.

Relatives of jailed political dissidents line up to pass food to their imprisoned loved ones. Since April 2018, hundreds of people have been jailed for taking part in unarmed anti-gov’t protests. In September 2018, the gov’t criminalized public protest. Inmates say they receive rotten, often inedible food.

Valle said police officers threatened to kill her as they drove her to the infamous El Chipote prison. Human rights workers and former inmates allege that torture there is routine. Valle said she was brought into a room of machine-gun toting men. She said they ordered her to admit that students had received arms to fight the Ortega government.

“I couldn’t say that because it’s not true,” she recounted to ReVista. Valle suffered three months of psychological terror in prison until she was released without explanation. Twelve days before her release on September 27, Valle’s father, Carlos, was jailed. He had been campaigning for his daughter’s freedom. Her family continues to face harassment by state agents.

Ex-guerrilla Carlos Humberto Silva Grijalva is proud to have been a part of the 1979 Sandinista revolution that toppled US-backed dictator Anastasio Somoza. The sign he made prior to a demonstration reads, ‘No more dictatorship, Ortega resign.’ Silva’s son, Carlos Humberto Silva Rodríguez, has been jailed on what one human rights worker said are fabricated charges of vandalism.

Nicaragua today is under siege by its own government. Since April 2018, at least 318 people have been killed. Hundreds of young people have been jailed. They represent a new generation of political prisoners in Nicaragua.

Human rights workers in Managua said the chaos triggered at least 30,000 people to leave the country between April and November 2018. “Nicaragua’s future is leaving,” lamented Carlos Tünnermann Bernheim, a former ambassador to Washington. “To be young and a student is a crime in the eyes of the Ortega government,” he said.

Student opposition to plans to reduce social security ignited simmering discontent with corruption and repression in April 2018. University students were branded as terroristas andgolpistas, the same term used to vilify anyone who demonstrates or speaks out against the regime. On multiple occasions, unarmed protesters have been attacked by stun grenades, tear gas and bullets fired by Nicaraguan police and their paramilitary allies.

“It’s state terrorism,” said Braulio Abarca, a lawyer at the Nicaraguan Center for Human Rights, known as CENIDH, in Managua. Weeks after speaking with ReVista, CENIDH’s legal status was revoked. Eight other non-governmental organizations (NGOs) were also stripped of their legal status. CENIDH had been chronicling alleged abuses by police and paramilitaries since violence began in April 2018, including the disappearances of 89 people. “We are living in fear,” said Abarca. CENIDH is continuing its work at a clandestine location.

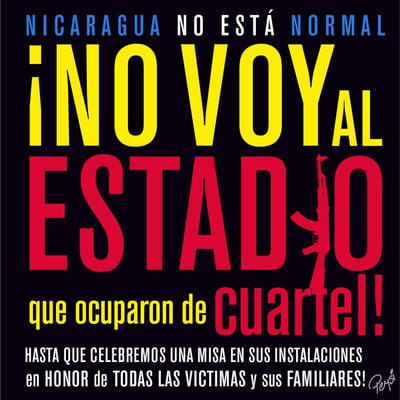

The ground crew prepares home plate for the start of the Liga Germán Pomares Ordoñez championship series at Estadio Nacional Dennis Martinez in Managua. Only a handful of spectators are in the 15,000 seat stadium. Paramilitaries are accused of shooting and killing people from the stadium’s top deck. Fans are boycotting the stadium.

Former guerrilla Carlos Humberto Silva Grijalva was jailed by the Somoza dictatorship. He said he remains a proud but jaded Sandinista. He said Sandinismo has been replaced by Orteguismo. “What we have today in Nicaragua has no relationship whatsoever to what we fought to create,” Silva said.

This pro-Ortega graffiti suggests that President Daniel Ortega not leave office before the scheduled 2021 election. Many sectors within Nicaragua are urging Ortega call early elections which he has so far refused to do. Pointing to U.S. sanctions as purported evidence, Ortega has claimed the U.S. is responsible for the civil unrest and violence. However, June 2018 CID/Gallup poll suggested 70 per cent of Nicaraguans age 16 years and older want Ortega to resign.

Spring/Summer 2019, Volume XVIII, Number 3

Lorne Matalon is a contributor to Marketplace, NPR and CBC Radio. His series on energy development in Mexico received a national Edward R Murrow Award for Investigative Reporting in 2016. In 2017, Matalon was the Energy Journalism Fellow at the University of Texas at Austin.

Related Articles

The University and the Nicaraguan Crisis

English + Español

University youth were the first to rise up in April in Nicaragua. Then other young people followed en masse, followed by the rest of the population. The young students woke up an entire country. “They are students; they are not delinquents!” became the first slogan that…

Nicaragua TEMPLATE: Single Language Article

English + Español

A one or two sentence blurb about the article

3, 2, 1… poemas

Manual para sobrevivientes…