No Apple a Day

Uninsured Latin@s

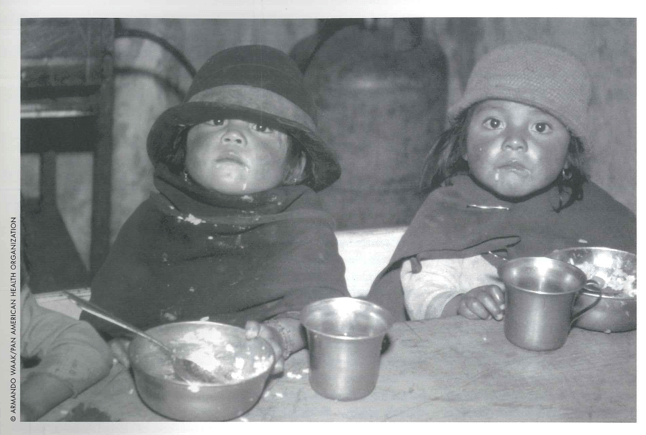

Children who immigrate to the United States, whether from Bolivia (left) or Belize, often find themselves without insurance.

One in three Latin@ immigrant children up to age 11 hasn’t visited a doctor during the past year. That’s about twice the proportion for Asian and white children in this age group. Among adolescents ages 12-17, half of Latin@ immigrant children (51%) hadn’t seen a doctor in the previous year, nor had 36% of Asian immigrant children and 26% of white immigrant children. As a result, these children are less likely to receive timely care for acute conditions such as ear infections, injuries, or communicable diseases. They are also less likely to have their chronic conditions, such as asthma or diabetes, diagnosed and appropriately managed, and less likely to receive preventive care.

Health insurance coverage is important because it promotes financial access to health care and protects families and individuals against potentially crushing medical costs. In examining how health insurance affects children’s access to health services, two measures are particularly telling: whether they have a connection to the health care system (indicated by whether the child has a regular source of care) and whether they visit a physician at least often enough to receive recommended preventive care.

Noncitizen Latin@ children have an uninsured rate (56%) that is more than twice that of noncitizen non-Latin@ white (“white”) children (25%) and more than five times the rate for white children with citizen parents (10%). Uninsured rates for Asian/Pacific Islander (“Asian”) and non-Latin@ white children are lower than for Latin@ immigrant children. But, as with Latin@s, within each ethnic group noncitizen children have the highest uninsured rates, about double or more the rates of citizen children with naturalized parents and children with U.S.-born parents.

Uninsured rates of children in noncitizen families rose since the enactment of welfare reform in 1996. Declining Medicaid coverage is driving these increases, adversely affecting the health care access for many children. These trends have a broad impact in the United States. One in five children in the United States is either an immigrant or has at least one immigrant parent, and many of these immigrant parents have not become citizens. Immigration and citizenship status have a profound effect on health insurance coverage and children’s access to health services. The 43% of noncitizen children who lack health insurance coverage of any kind is more than triple the rate for children of U.S.-born or naturalized parents. And for children who are U.S. citizens but whose parents are, uninsured rates are approximately double those of children whose parents are citizens.

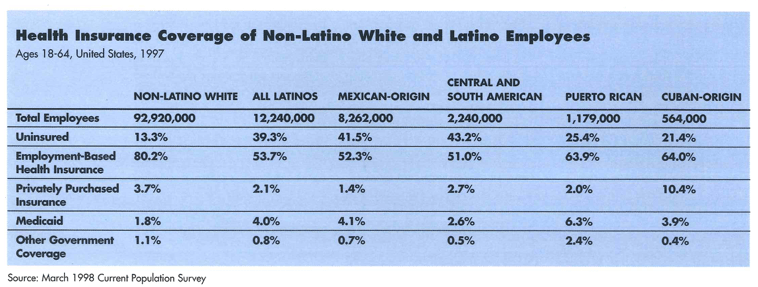

The citizenship status of a child and of the child’s parents strongly affects whether that child is uninsured in nearly every family income group, across ethnic groups, and at all family work-status and parental-education levels. Nine out of 10 uninsured children are in families with at least one working adult, regardless of the immigration/citizenship status of a child or his or her parents. More than half of uninsured children, both citizen and noncitizen, are in full-time, full-year employee families. However, since many workers are employed in minimum wage jobs without benefits, being employed is no guarantee of health care.

Education is a major determinant of employment opportunity. Nearly half of noncitizen children and citizen children with noncitizen parents live in families in which the primary breadwinner has less than a high school degree, and only one-third have parents who have had at least some college. Poverty and lack of opportunity in their country of origin drove many from school at earlier ages than is typical in the United States, restricting employment opportunities in their new country. In contrast, among children whose parents are naturalized or U.S.-born citizens, more than four out of five parents have at least finished high school.

Despite the booming economy during that latter 1990s, these conditions did not improve much for children in immigrant families. Employment-based health insurance coverage remained statistically unchanged between 1995 and 1997 for children in most family immigration and citizenship groups. During the same time period, however, Medicaid coverage fell by more than six percentage points for citizen children of noncitizen parents, and by more than five percent-age points for noncitizen children. As a result, uninsured rates rose for these noncitizen families. The declines in Medicaid coverage occurred, in large part, in response to changes in public policy, mainly those related to welfare reform. Many low-income families lost welfare benefits, including Medicaid, when they took low-wage entry-level jobs that did not provide health insurance. In addition, many noncitizen children and citizen children in noncitizen families feared that enrolling or remaining in Medicaid would threaten their immigration status.

For low-income citizen children with U.S.-citizen parents, Medicaid or the new Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) can offset poor access to job-based insurance. Noncitizen children and U.S.-citizen children with noncitizen parents, however, have not received this protection to nearly the same extent. Only about one-third of noncitizen children living in poverty receive Medicaid coverage, compared to more than half of citizen children, regardless of their parents’ citizenship status.

Immigration laws and, more recently, welfare reform legislation have created distinctions among children based on their or their parents’ immigration status. For example, because Southeast Asian immigrants qualify as refugees, their children are better protected by Medicaid. Just one in four (25%) Southeast Asian noncitizen children is uninsured because half (50%) are covered by Medicaid. In contrast, only 17% of noncitizen children from Mexico receive Medicaid coverage, leaving 60% uninsured. Although nearly all states have extended coverage to pre-welfare reform legal immigrants (those who resided in the United States when the legislation was enacted on August 22, 1996) and Congress has reinstated Medicaid eligibility for some groups it had excluded, many noncitizen families have avoided the Medicaid program due to concerns of being labeled a “public charge.” They fear that enrolling even their citizen children in means-tested programs, such as Medicaid or their state CHIP plan, would be used against them when they try to renew their visas, return to the United States after traveling abroad, or apply for citizenship.

Along with other aspects of welfare reform, these provisions are most likely responsible for much of the net increase in the uninsured rates among noncitizen families from 1995 to 1998. The fears of some immigrants may be allayed by recent policy changes concerning Medicaid enrollment and immigration status. The INS and the State Department ruled in May 1999 that noncitizens will not be classified as “public charges” if they or their children enroll in Medicaid or CHIP (except those who receive long-term care under Medicaid). This policy change, if effectively communicated to parents, should help assure families that they do not have to fear these programs. Nevertheless, children who immigrate legally to the United States after August 22, 1996 will continue not to be eligible for Medicaid (except nonemergency services) unless their families are refugees or asylees and then, only for five years. President Clinton has proposed extending eligibility to these recent arrivals. For immigrant parents who are undocumented, however, fear of the INS may deter them from applying for either program even when their children are U.S. citizens and thus fully eligible for all benefits available to other citizens.

Despite the overriding importance of health insurance, many immigrant families experience additional barriers in seeking access to physicians. Even among insured children, those who are immigrants are one-and-a-half times as likely as nonimmigrants to have gone more than a year without visiting a physician. Language and cultural barriers undoubtedly play an important role in reducing their access. Community clinics and other safety-net providers often help to promote access, for the insured as well as for the uninsured.

Policies that strengthen the health care safety net would enhance access for many immigrants as well as for other underserved groups. The growth and healthy development of these children are an important concern to all Americans. One in five children is an immigrant or has immigrant parents. They are a significant part of communities in which they live, and they will become a major segment of the nation’s workforce in the 21st century.

Because many immigrant parents are noncitizens, they have been discouraged from enrolling their children in Medicaid or other public health insurance programs. At the same time, their access to job-based insurance is restricted by a variety of factors. The effect of these patterns has been to curtail their children’s access to essential health services. Congress can improve the access of noncitizen children and citizen children in immigrant families in two ways: by extending Medicaid and CHIP coverage to all legal immigrants on the same basis as for citizens, and by strengthening funding for the health care safety net.

Fall 2000

E. Richard Brown is the director of the University of California, Los Angeles Center for Health Policy Research and a professor at the University of California, Los Angles School of Public Health. Roberta Wyn and Victoria D. Ojeda contributed to this article, which was adapted from a Policy Brief by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, supported by a grant from The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. For more information, see http://www.healthpolicy.ucla.edu

Related Articles

Physicians for Human Rights

As a member of a 1983 American Public Health Association delegation to evaluate medical neutrality in El Salvador, I saw mothers and children begging for food and for help in getting…

Medicinal Herbs in Times of Low Intensity War

Julio was wet from the pouring rain and frightened. He ran through the streets of Polho, a community in Chiapas sympathetic to the Zapatista rebels, to find Carlos, the health promoter…

A Latina Looks at Disparities

It was my first year of medical school in a new city far from home. I came to Harvard Medical School in the fall of 1999 with many preconceived notions of what I would encounter. Coming…