Oscars for Mexican Filmmakers

But Where Are the Mexican Films?

A couple of years ago, in 2007, the so-called Three Amigos (the filmmakers Alfonso Cuarón, Guillermo del Toro and Alejandro González Iñárritu) went up on stage for the 79th Oscar Awards presentations. Their three films (Children of Men, Pan’s Labyrinth and Babel, respectively) garnered a total of sixteen nominations for the golden statuette (ten of them for people born in Mexico). Together, they won four of the Oscars handed over that night and a contract with Universal for $100 million dollars to produce five movies, one or two of them in Spanish.

On the other side of the border, the event was much celebrated and publicized. This national triumph had great symbolic value for Mexico. These directors and other Mexican artists had managed to realize the American dream by directing Robert de Niro, acting alongside of Brad Pitt, and working as photography directors for Tim Burton or the Coen brothers. Film criticism in Mexico, sometimes excessively condescending, at other times extremely harsh, was polarized between critics who unabashedly praised the filmmakers for displaying high technical expertise and notable aesthetic quality in these multimillion dollar projects, and commentators who considered these films to be mere “popcorn movies,” commercial factory piecework that erased national identity and eclipsed true Mexican films with cultural values that defined the country or that had taken risks to create formal avant garde experiments. Regardless of this polemic (impossible to resolve in this space), the night of the 2007 Oscars could also be said to demonstrate a historic inertia of cinematography in a country which had been capable of generating its own export-quality movies. In this, the relations between Mexico and the United States have played a fundamental role that is responsible for the present situation—not only cinematographic, but also the economic, political, social and cultural. Let us use the flashback technique to explain some of the background that led to the night when the Three Amigos took each other’s hands and greeted the audience in the movie awards ceremony seen throughout the world.

The initial point of departure for any discussion of Mexican film is its so-called Golden Age, whose exact dates are defined differently by different commentators. In “El cine nacional,” for example, Carlos Monsiváis places the era from 1930 to 1954, while Rafael Aviña and Gustavo García situate its beginning in 1936, the year of the legendary film Allá en el Rancho Grande. In any case, the period encompassed a little less than thirty years and managed to dominate the film industry in Latin America, with the exception of Argentina. Mexico made the most widely seen films in Spanish on the continent, including in Brazil and the United States; here, in 1950, 300 movie houses showed Spanish-language films, mainly Mexican movies.

Commercial success led to thematic richness in the film industry. Producers made movies of an expressionist nature such as Dos monjes (1934), political-historical films such as ¡Vámonos con Pancho Villa! (1935) or films dissecting specific sectors of the society such as the family in Una familia de tantas (1934) or immigrants to the United States in Espaldas mojadas(1953). Only a strong film industry could receive exiled Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel and help revive his career, or let a terribly bad filmmaker, Juan Orol (the local Ed Wood), write, direct, produce, act in and compose the music for a movie in which Mexican charros—a type of Mexican cowboy—defend the national sovereignty when threatened by the Chicago Mafia (Gángsters contra charros, 1947). This peculiar and weird film demonstrates the good health and diversity of a cinematography capable of making 108 movies in 1949 and 150 in 1950, in contrast to the harsh and sad reality of the end of the century, when only thirteen movies were made in 1997.

In this entire Mexican Belle Époque, Mexico-United States relations were notably important. The first factor that should be mentioned—a commonplace for all references regarding this period—was Mexico’s northern neighbor’s entry into World War II. The U.S. film industry needed to ration its production of celluloid (the material for making film) and to concentrate its movie production on war-related movies and propaganda. Thus, although it continued to be the dominant industry in the world, it had to cede a bit of room to its neighbors. In addition, European film, the second dominant market in Latin America, directly suffered the effects of the war. Mexico took advantage of the situation when it declared itself an ally of the United States against the German-Italian-Japanese axis. Its Spanish-language film competitors fell behind: Spain was recuperating from a civil war, and Argentina was trapped in its relationship with Germany and Italy. Hence the Mexican movie industry flourished and expanded throughout the continent.

In addition to the factor of the war, the Golden Age of movies in Mexico was strengthened by closeness to Hollywood. The proximity of the border allowed many Mexican technicians and film artists to develop their skills in the United States and to learn from Hollywood the difficult art of making movies. The most notable case—because of its importance and because it serves as a microcosm of the relationship between the two neighbors—is that of the group made up of Emilio Fernández (director), Gabriel Figueroa (cinematographer) and Dolores del Río (actress). This group is unanimously considered by critics as the crew that brought film aesthetics of Mexico to its highest point during the Golden Age in the middle of the 20th century, a status that even today no one has been able to attain. All three had been in Hollywood under different circumstances, and each one was representative of the diverse strata of Mexican society.

First, there is Emilio Fernández, the wetback who worked his way up to learning how to make movies after laboring as bricklayer, longshoreman and waiter in Chicago and Los Angeles. He then became an apprentice in several movies, where he learned a bit of everything and was a specialist in nothing. Later, thanks to his athletic figure, he was hired as a double and an extra in movies, including a few for Douglas Fairbanks. The “Indio” —the Indian—(a nickname he wore with honor) is even said to have been the model who posed for the Oscar statuette, an unlikely tale but indicative of his striking looks. Fernández arrived in Hollywood in the 1920s, when the cinematographic development of silent films had reached its peak after its institutionalization with films such as Intolerance in the previous decade. It was also in California where “El Indio” learned of an unfinished film that affected him deeply: Sergei Eisenstein’s ¡Que viva México!, about which he declares, “This is where I learned the pain of the people, the land, the strike, the struggle for freedom and social justice. It was wonderful.” This statement is in and of itself an aesthetic declaration that Emilio Fernández would abide by to the end.

The inspiring mix of the North American film and the Soviet director would influence Fernández significantly after he returned to Mexico and became the author of Flor Silvestre, Enamorada, Río Escondido, María Candelaria and Salón México, among his most significant films. As does Almodóvar today, Fernández stylized melodrama in such a fashion as to give it a tragic aspect and transform it into something greater that could effectively transmit the values of a post-revolutionary Mexico. The idealization and exaltation as a way to construct the identity of the country led the director to create diverse mythic figures that have survived in the local imaginary (the Peasant, the Motherland, the Mother, Providence, all with capital letters). He is, without a doubt, the most nationalist among nationalist filmmakers and this turned him, for better or worse, into one of the few Mexican film directors, perhaps the only one, that has made it to a select pantheon known as authors’ films. The grandfather of the Three Amigos returned from the United States to his country of origin, not to reencounter but to reinvent it and this was somethg he never would have been able to accomplish without the experience of living in the United States, distanced from his home country.

The director would not have accomplished much without the help of another notable artist: the cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa, who also had his own experience in Hollywood. If Emilio Fernández crossed the border as a wetback, Figueroa did so through networking among producers. Figueroa received a scholarship in 1935 from the Mexican film company CLASA to study with the legendary Gregg Toland, who later would become the cameraman for Citizen Kane and also would take charge of teaching Orson Wells about the language of film. Just as Eisenstein was important for Fernández, Toland’s style would mark Figueroa and through him the entire Mexican film industry, with the use of deep focus in which the depth of field is increased and the cinematographic space is expanded. The “Indio” and Figueroa learned to optimize this resource to capture the Mexican landscape, imbuing it with a lyrical essence. Through Figueroa, Mexican photography turned into a school with a certain prestige in the world, to the degree that today, fifty years later, there are at least five Mexican cameramen filming in Hollywood and winning Oscars for which Figueroa was nominated, but did not win.

Last but not least is Dolores del Río, who arrived in Hollywood in a very different manner. Unlike Figueroa and Fernández, the future star of the Golden Age was a member of Mexico’s wealthy upper class and emigrated to California—to the circles of the jet set—after the upheaval of the Mexican Revolution. Del Río became an actress in silent films and made about 30 movies, many of them very successful and of the highest quality. She worked with highly regarded directors such as Raoul Walsh, King Vidor and Busby Berkeley, and in 1928 even managed to make a hit as a singer on the soundtrack of the silent film Ramona. Although she contributed to the promotion of the Latin stereotype, her elegant and aristocratic beauty, together with a true dramatic talent, made her a diva in her time; while a minor diva alongside some of the great divas of the period, she achieved greater fame than contemporary Mexican actresses like Salma Hayek, who has not managed to achieve a high-quality role in her North American experience. Unlike other non-English-speaking actors, Dolores del Río made an easy transition from silent film to the talkies and managed to continue her career in the United States. In 1942, getting close to 40 and knowing that Hollywood tended to put older actresses out to pasture, she decided to return to Mexico. There she met with intellectuals and artists, among whom was “Indio” Fernández. The director offered her the lead role in Flor Silvestre and this would begin the second act of her career, the face of love and feminine anguish of Mexican melodrama.

The director, the photographer, the actress. The wetback, the exchange student, the aristocrat. All the cinematographic sectors and the social strata of Mexico were enriched through this experience. U.S. cinematography gave them the technical expertise and allowed them to encounter their own cultural values that they later developed on returning to their native land. There are also other examples, such as Gonzalo Gavira, the first Mexican to win an Oscar; his award was for the sound effects in The Exorcist. Gavira managed to create peculiar sounds with ordinary objects, such as the possessed girl’s famous turn of the head, a sound that he made with a comb. Another success story is that of Luis Mandoki, the first true filmmaker of this new bevy of directors at the end of the 20th century. Mandoki emigrated to California as a result of the Mexican economic crisis and achieved a certain prestige in Hollywood; years later, in a curious reversal, he returned to Mexico to support the causes of the Mexican and Central American left, making leftist, politically committed films.

Given this history, it is not surprising to see the Three Amigos on stage for the 79th Oscar ceremony. González Iñárritu, Cuarón and del Toro are products of the Mexican film industry, which, even in crisis, still maintains the infrastructure forged in the years of splendor, enabling it to develop quality movies within the scope offered by the commercial and political relations with its northern neighbor. In spite of this history of being good neighbors in the film industry, there are elements that have negatively affected the Mexican film industry, bringing about its present crisis. The free market strategy, especially through NAFTA, has constrained cinematography south of the Bravo River and has permitted U.S. monopolies to dominate the Mexican movie houses. For example, in 2000, 84.2% of films shown in Mexico were from the United States, while 8.3% were Mexican, according to cultural critic Néstor García Canclini. The vicious cycle this produces is evident: if Mexican films do not profit from or recoup their investment, movie production is cut back and thus fewer local films are shown. In response, the Mexican filmaking community has often protested, including a 1998 international symposium that was called Los que no somos Hollywood (“Those of Us Who Are Not Hollywood”). These protests resulted in an effort to implement a law to protect the Mexican cinematographic market, a law that was completely rejected by Jack Valenti, director of the Motion Picture Association of America and by the U.S. government itself. The law, of course, never went into effect. Despite these problems, thanks to new digital technologies and the participation of the Mexican government, 70 movies were made in 2008, but only 46 of them were ever shown, and as a result the audience for local movies decreased dramatically. The artificial lifeline that the Mexican state has granted to the movie industry will not help if there is no fair competition within the local market and the Mexican film industry will continue to be in crisis for at least the next few years. This problem can be seen as a microcosm of what has happened in other areas—economic, social, cultural and political—of U.S.-Mexico relations. On one hand, the strong U.S. filmindustry has directly permitted the strengthening of the Mexican industry, but at the same time, power of the former diminishes the latter. But one should not forget the fact that in its turn, México dominated the Latin American film industry in the middle of the last century and hindered cinematographic development in other Latin American countries as a result of the inevitable spiral of the big fish gobbling up the smaller ones. The strengthening of national film industries is not possible without strengthening the economy and public policy in each country; at the same time, a robust film industry reflects the autonomy and strength of an economically healthy and democratic country (film in totalitarian governments should be considered as a separate, distinct case). The best way to guarantee that many more “Tres Amigos” will emerge and that new artistic talents will be developed in other Latin American nations is to guarantee the economic and social health of those nations. Utopia is still desirable—and still possible.

Algunos aspectos de las relaciones cinematográficas entre México y los Estados Unidos (Spanish version)

Por Humberto Delgado

Hace poco tiempo, en el año 2007, los llamados Three Amigos (los cinerealizadores mexicanos Alfonso Cuarón, Guillermo del Toro y Alejandro González Iñárritu) subieron al escenario de la 79ª premiación del Óscar. En total, sus tres películas (Children of Men, Pan’s Labyrinth y Babel, respectivamente) alcanzarían dieciséis nominaciones a la estatuilla dorada (diez de ellas para gente nacida en México). Conjuntamente ganarían cuatro de los Óscares entregados esa noche y un contrato con Universal por cien millones de dólares para producir cinco películas, una o dos de ellas en español.

Del otro lado de la frontera el asunto fue muy celebrado y difundido. Este triunfo nacional mucho tenía de simbólico para el país. Estos artistas emigrantes habían logrado cumplir el sueño americano y eran capaces de dirigir a Robert de Niro, actuar al lado de Brad Pitt o ser directores de fotografía de Tim Burton o los hermanos Coen. La crítica cinematográfica en México, a veces excesivamente condescendiente y otras radicalmente dura, se polarizó entre quienes alababan la entereza con que estos cineastas asumían con éxito proyectos de millones de dólares, con un dominio técnico y estético notable, mientras otros consideraban esas mismas películas meros popcorn movies, maquila comercial que borra las huellas de la identidad nacional y eclipsa las verdaderas películas mexicanas, aquellas con valores culturales que definen al país o que bien han corrido los difíciles riesgos de crear las experimentaciones formales del avant-garde fílmico local. A pesar de esta polémica (imposible de resolver en este espacio) la noche de los Óscares del 2007 es, efectivamente, el resultado de una inercia histórica en un país que fue capaz de generar un cine propio con calidad de exportación. En todo esto, las relaciones entre México y Estados Unidos han jugado un papel fundamental que mucho ayudan a entender este presente –no sólo cinematográfico- sino también económico, político, social y cultural. Por todo lo anterior, es conveniente hacer un flash back que explique algunos antecedentes previos que han originado esa noche en que los Three Amigos se tomaban de la mano y saludaban a la audiencia de la ceremonia cinematográfica más vista en todo el mundo.

El referente inicial de cualquier discusión de cine mexicano se establece en su llamada Época de Oro cuyas fechas fluctúan entre los distintos autores que se refieren a ello. Carlos Monsiváis, por ejemplo, la ubica en el periodo que va de 1930 a 1954, mientras otros, como Rafael Aviña y Gustavo García, la sitúan en 1936, año del estreno de la mítica Allá en el Rancho Grande. En todos los casos se piensa que fueron poco menos de treinta años de una industria dominante en toda Latinoamérica (con la excepción de Argentina), siendo la cinematografía en español más vista en el continente, incluso en Brasil y Estado Unidos; en este último país, como dato curioso, en 1950 había en Nueva York 300 salas dedicadas al cine en lengua española que principalmente exhibían películas mexicanas. El éxito de mercado ocasionó una riqueza temática en la filmografía del país. Se podían realizar películas de corte expresionista como Dos monjes, histórico-políticas como ¡Vámonos con Pancho Villa! o diseccionar sectores específicos de la sociedad, como en Una familia de tantas o en Espaldas mojadas. Sólo una industria cinematográfica tan fuerte fue capaz de asilar y revivir al español Luis Buñuel o de permitirle a un cineasta terriblemente malo como Juan Orol (el Ed Wood local) escribir, dirigir, producir, actuar y componer la música para una película en donde los charros mexicanos defienden la soberanía nacional amenazada por la mafia de Chicago (Gángsters contra charros, 1947). Este último dato, además de divertido, demuestra la buena salud y variedad de una cinematografía capaz de realizar 108 películas en 1949 y 150 en 1950, en contraste con la dura y triste crisis del fin de siglo mexicano, en donde, por ejemplo, sólo se pudieron filmar 13 en 1997.

En toda esta Belle Époque, las relaciones México-Estados Unidos tuvieron una importancia notable. El primer aspecto que debe mencionarse –y como lugar común en todas las referencias respecto a este periodo- se encuentra la entrada a la Segunda Guerra Mundial del vecino del norte. La industria cinematográfica americana se vio en la necesidad de racionar su producción de celulosa (con la que se fabrica la película) y concentrar un buen número de su filmografía a temas de guerra y propaganda. Además, a pesar de que este país continuó siendo la industria dominante en el mundo, tuvo que ceder en algunas de sus habituales políticas de expansión con sus vecinos. Por otro lado, el cine europeo, segundo mercado dominante en Latinoamérica, sufría en carne propia los estragos de la guerra. México aprovechó muy bien la situación al declararse parte de los Aliados que combatían contra el Eje Alemania-Italia-Japón. No sucedió lo mismo con sus más cercanos competidores de habla hispana (España y Argentina, el primero recuperándose de una guerra civil, el segundo atrapado en sus relaciones con Alemania e Italia), por lo que el florecimiento y expansión del cine mexicano comenzó a germinar por todo el continente.

Además del factor de la guerra, la Época Dorada del cine en México se vio fortalecida por otro aspecto de esta cercanía con Hollywood. La proximidad de las fronteras hizo que muchos técnicos y artistas mexicanos se desarrollaran en los Estados Unidos y aprendieran en esa industria el duro arte de hacer cine. El caso más notable –por su importancia y porque encierra el microcosmos de esta relación entre vecinos- es la del grupo conformado por Emilio Fernández (director), Gabriel Figueroa (cinefotógrafo) y Dolores del Río (actriz). Este grupo es considerado unánimemente por toda la crítica como el crew que llevó la estética fílmica de ese país a su punto más alto durante ese periodo dorado de la mitad de siglo XX, circunstancia que, hasta el día de hoy nadie ha podido alcanzar. Cada uno de estos tres personajes de la vida mexicana estuvieron en Hollywood bajo circunstancias diferentes y muy representativas de los diversos estratos de su sociedad.

En primer lugar, está el caso de Emilio Fernández, el wet back que aprende a hacer cine desde abajo, personaje que antes de ser director fue albañil, estibador y mesero en Chicago y los Ángeles para luego participar en varias películas como aprendiz de todo y especialista en nada. Posteriormente, gracias a su figura atlética se convierte en doble y extra de cine, entre otros para Douglas Fairbanks. El “Indio” (sobrenombre que llevaba con orgullo) incluso presumía haber sido el modelo que posó para la estatuilla de los Óscares, leyenda improbable pero significativa de su personalidad. Fernández llega al Hollywood de los años 20´s, en los cuales el lenguaje cinematográfico silente alcanzaba su esplendor luego de su institucionalización por medio de filmes de finales los años 10´s, como Intolerance. Es también en California en donde “El Indio” conoce una obra que lo marcaría profundamente: la inacabada ¡Que viva México!, de Sergei Eisenstein, de la cual señala: “This is what I learned the pain of the people, the land, the strike, the struggle for freedom and social justice. It was wonderful”. Esta declaración es en sí misma un pronunciamiento estético que Emilio Fernández llevará hasta sus últimas consecuencias.

La mezcla explosiva entre el cine norteamericano y el director soviético influirán en Fernández notablemente y lo llevarán a regresar a México para convertirse en el autor de Flor Silvestre, Enamorada, Río Escondido, María Candelaria y Salón México, entre sus más destacados filmes. Como Almodóvar en la actualidad, el melodrama es el género que estiliza hasta darle visos trágicos y convertirlo en algo más, en el medio eficaz para transmitir los valores del México postrevolucionario. La idealización y exaltación como medio para construir la identidad de su país lo lleva a crear diversas figuras míticas que han pervivido en el imaginario local (el Campesino, la Patria, la Madre, la Provincia, así, con mayúsculas). Es, sin duda, el más nacionalista entre los cineastas nacionalistas y eso lo convierte, para bien o para mal, en uno de los pocos directores mexicanos, tal vez el único en verdad, que ha llegado a ese difícil panteón conocido como cine de autor. El abuelo de los Three Amigos regresaba de los Estados Unido a su lugar de origen, no para reencontrarse con su país sino para reinventárselo.

Este director nada hubiera logrado sin la ayuda de otro artista notable: el cinefotógrafo Gabriel Figueroa, también con su propia experiencia en Hollywood. Si Emilio Fernández cruza la frontera como mojado, Figueroa lo hace a través de las relaciones entre productoras. Figueroa es becado en 1935 por la compañía de cine mexicana CLASA para estudiar con el mítico Gregg Toland, quien tiempo después sería el fotógrafo de Citizen Kane y también se encargaría de enseñarle el lenguaje fílmico a Orson Welles. Si Eisenstein fue importante para Fernández, el estilo de Toland marcaría a Figueroa y con ello al cine mexicano por medio del uso del pan focus en el que la profundidad de campo se incrementa y el espacio cinematográfico se expande. El “Indio” y Figueroa aprendieron a optimizar este recurso para capturar el paisaje mexicano hasta darle alcances líricos. A partir de él, la fotografía mexicana se convertirá en una escuela con cierto prestigio en el mundo, al grado de que hoy en día, cincuenta años después, hay al menos cinco cinefotógrafos mexicanos filmando en Hollywood y ganando el Óscar al que años atrás Figueroa estuvo nominado pero no ganó.

Last, but not least, debe hacerse mención de Dolores del Río, quien llega a Hollywood de manera muy diferente a Figueroa y Fernández. A diferencia de ellos, la futura estrella de la Época de Oro pertenecía a las clases altas de su país y emigra hacia las esferas del jet set californiano debido a las consecuencias que la Revolución Mexicana provoca en ciertos sectores adinerados de la sociedad local. Del Río se convierte en actriz del cine mudo estadounidense, filma aproximadamente 30 películas, muchas de ellas con enorme éxito y calidad. Trabaja con directores de la talla de King Vidor o Busby Berkeley e incluso alcanza en 1928 un hit como cantante con el soundtrack del film silente Ramona. A pesar de que contribuye a promover el estereotipo latino, su belleza elegante y aristocrática, sumada a un verdadero talento dramático la convirtió en una diva de la época, si bien menor al lado de las grandes divas de ese periodo, pero lo cierto es que en su momento alcanzó mayor notoriedad en Hollywood que actrices mexicanas contemporáneas como Salma Hayek, quien, a pesar de su fama, jamás ha logrado concretar una interpretación de buena calidad en su experiencia norteamericana.

A diferencia de otros actores de habla no inglesa, a Dolores del Río le fue fácil su transición del cine mudo al sonoro y logra continuar su carrera en los Estados Unidos. En 1942, ya próxima a los 40 años de edad y sabiendo que en Hollywood eso le restaría trabajo, la actriz regresa a México. Allí se reúne con intelectuales y artistas entre los que conoce al “Indio” Fernández. El director le ofrece su primer protagónico en Flor Silvestre y comenzaría allí un segundo aire en su carrera, transformándose en el rostro del amor y dolor femenino del melodrama mexicano.

El director, el fotógrafo, la actriz. El wet back, el estudiante de intercambio, la aristócrata. Todos los sectores cinematográficos y los estratos sociales de México se enriquecen por medio de esta experiencia. La industria cinematográfica americana les otorga un dominio técnico y les permite encontrar sus propios valores culturales que luego desarrollarían en su propio país. Existen también otros ejemplos, como el caso de Gonzalo Gavira, primer mexicano en ganar el Óscar, su premio fue por los efectos de sonido de The Exorcist. Gavira lograba hacer ruidos peculiares con objetos comunes, como el famoso giro de cabeza de la niña poseída, sonido que hizo con un peine. También debería mencionarse a Luis Mandoki, primer verdadero cineasta de esta nueva camada de directores de fin de siglo, Mandoki emigra a California ante la crisis económica mexicana y alcanza cierto prestigio en Hollywood; años después, en una curiosa reconversión, regresa a su país para apoyar las causas de la izquierda nacional y centroamericana, realizando películas comprometidas con su posición política.

Puede verse en todos los casos anteriores que no es casual esa noche en que los Three Amigos subieron al escenario de la premiación 79 del Óscar. Iñárritu, Cuarón y del Toro son producto de una industria mexicana, que si bien está en crisis, tiene al menos una infraestructura que sus años de esplendor forjó y que podría desarrollar un cine de calidad en tanto existieran condiciones distintas en las relaciones comerciales y políticas con su vecino del norte. A pesar de esta historia de buena vecindad cinematográfica, hay elementos negativos en esta relación que han afectado al cine mexicano. La crisis actual del cine mexicano se debe en parte a esto. La liberación de los mercados, en especial a través del NAFTA, ha constreñido la cinematografía del sur del río Bravo y ha permitido que los monopolios estadounidenses dominen las salas cinematográficas mexicanas. Por ejemplo, en el año 2000 se exhibieron 84.2% de películas estadounidenses en tierras aztecas y 8.3% de filmes mexicanos. El círculo vicioso que esto conlleva es evidente: si las películas nacionales no se exhiben no se recupera el dinero ni hay ganancia para los inversionistas, lo que provoca que la producción de cine se reduzca y como consecuencia haya poca exhibición de cine local. Ante esta grave crisis, la comunidad cinematográfica mexicana ha protestado constantemente, incluso por medio de un simposio internacional durante 1998 que nombraron Los que no somos Hollywood. El resultado de estas protestas ocasionó que se intentara implementar una ley para proteger el mercado cinematográfico mexicano, ley que es enteramente rechazada por Jack Valenti, director de la Motion Picture Association of America y por el mismo gobierno norteamericano. La ley, por supuesto, nunca entra en vigor. Este tipo de monopolios no sólo evita el desarrollo del cine mexicano sino incluso el propio desarrollo del cine independiente norteamericano.

A pesar de estos problemas, gracias a las nuevas tecnologías digitales y a la participación del gobierno mexicano, en el 2008, al igual que en el año anterior, se realizaron 70 filmes, pero sólo lograron ser exhibidos 46 y la audiencia para el cine local tuvo un decremento de 3 millones de personas. La vida artificial que el estado mexicano le otorga al cine en nada ayudará si no existe una competencia justa al interior del propio mercado local.

En todas estas experiencias, las relaciones entre estos dos países han sido estrechas y paradójicas. Por un lado, la fuerte industria estadounidense ha permitido fortalecer directamente la cinematografía mexicana, pero es esta misma fuerza la que logra empequeñecerla. El cine es una manifestación cultural de un país, un medio capaz de ayudar a la conformación de una identidad nacional. La apuesta segura para que haya más mexicanos (y gente de todo el mundo) recibiendo premios internacionales de cine sólo puede lograrse si se fortalecen las cinematografías locales. La inercia de la Época de oro del cine mexicano llevó a estos Three Amigos a filmar en Hollywood, el tiempo dirá si estas nuevas relaciones comerciales permitirán nuevas generaciones de artistas mexicanos de importación.

Fall 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

Humberto Delgado is a third-year doctoral student of Latin American literature in Harvard’s Departament de Romance Languages and Literatures. He studied Latin American literature at the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México (UAEM) and later film directing at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), where he also received a Master’s in Communications Studies.

Humberto Delgado es estudiante de tercer año de literatura latinoamericana en el Departamento de Lenguas y Literaturas Románicas de Harvard. Estudió literatura latinoamericana en la Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México (UAEM) y posteriormente dirección cinematográfica en la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), donde también recibió una Maestría en Estudios de la Comunicación

Related Articles

Coconut Milk in Coca Cola Bottles

Common knowledge has it that virtually any movie, once removed from its original cultural context of production and reception, might be either misunderstood and misperceived or re-interpreted and re-signified. Likewise, we may agree that national cinemas seek to define, challenge….

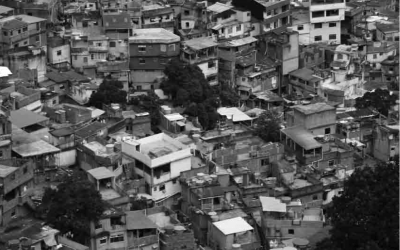

Neither the Sertão or the Favela

To frame the poetics of the ordinary in terms of subtlety and delicateness is to propose an antidote both for cynicism and for what I call Neo-Naturalism. Its appearance, at least in Brazilian cinema and literature, has been clearly identified, ranging from peripheral subjects…

Brazilian Cinema Now

Snow falling in the city of São Paulo, in southern Brazil? Taking a helicopter in São Paulo then arriving a few moments later in the deep wilderness of the Amazon jungle, half a continent further away to the north? Then meeting a white Asian tiger in the heart of the Amazon forest?…