Photoessay: Documenting Violence

I have file drawers filled with dramatic photographs of broken bodies, rage, terror, anguish and mayhem. These images map nearly two decades covering revolution, urban crime and state repression, as well as more intimate facets of violence in the Americas. The repeated witnessing of such trauma often leaves one feeling inadequate. The ripple effects of mayhem and the attempt to draw meaning from it, to provoke outrage or to transcend the suffering are struggles that create a bond between the witness and those whose sufferings are much deeper. My work has taken new directions, as I search among survivors, for those struggling to make sense of the senseless, to find a narrative that permits hope.

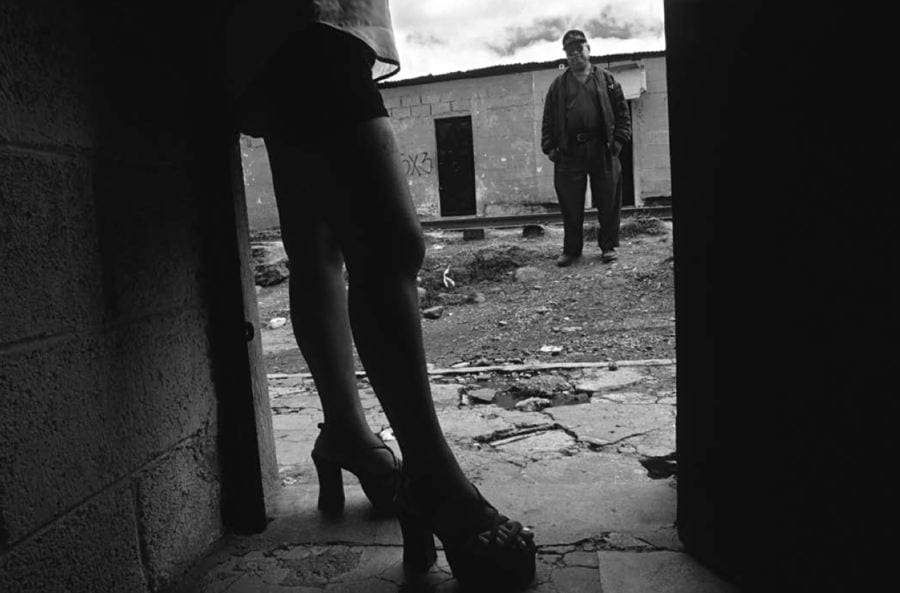

Hope begins with safely being able to speak truth. But my subjects—many of whom are women and children—live with a burden of fear and stigma. Whether these women are living with HIV, surviving as prostitutes, or struggling with the physical and emotional scars of war, the fact that they have been violated does not save them from being treated as outcasts or blamed for situations over which they have little control.

As women and children in Guatemala and Colombia know, showing your face while speaking honestly can get you killed. And yet, the children especially crave recognition. As soon as they spotted my camera, they were eager for fame or immortality. “Oh, take my picture,” they said, but a moment later, their expressions turning sober, they would add, “Just please don’t show it here.”

Any illusion that photographers can control where or how our images appear dissolves in the age of the Internet. An image that exists in a public sphere can be instantly copied and distributed whether or not its publication is intended or officially sanctioned. How to depict suffering and injustice without exposing those violated to further stigma or harm has become much more difficult. The ubiquitous reach of the Internet penetrates even remote areas of Guatemala and Colombia.

Knowing that I couldn’t control local exposure of my images, I needed to find a way of working that would protect my subject’s identities, allay their fears, and empower them to speak truthfully about their lives. Those who feel imprisoned by stigma need to have a context in which they can exercise control. When a child asked if he could pick a different name to accompany his photographs and story, it occurred to me that he was really asking to share control. This inspired me to look for ways to make the image-making process collaborative.

With adults I let the interview suggest ways to make the image. We discuss how to convey metaphorically or with artifacts central elements of their narrative. With the children the image often comes first. It is more like a brainstorming game. In this playful dance of posing and waiting for a spontaneous gesture, an expression of candor, or an image that provides context, we learn to trust each other and they are able to share their secrets.

In 2000, nancy and six siblings survived one of Colombia’s most brutal para- military massacres. nancy, 24, now works with a support group for women affected by the war. “the desire for vengeance is one of the roots of the violence we live… at the time of the massacre i wanted the electric chair for every one of them. now i would ask the paramilitaries who committed the massacre, “how would you feel if this had happened to you, to your family?”…i do want them to at least imagine what it would feel like to be be us…”

When misrael was seven, his father was murdered and his home life began to fall apart. living in the streets, he became addicted to crack. he began living with a prostitute who gave him drugs for sex. When she died of hiV he began feeling sick. “they tell me i have that sickness that kills you. i feel weak because of all that i’ve been through. but i hope maybe i don’t have hiV.” Since moving to a shelter misrael has been hospitalized with HIV-related illness. he is no longer in denial about his status and has been taking antiretroviral drugs.

“Tomás,” 15, lives in a home for demobilized combatants sponsored by the Colombian Family Welfare institute. running away from home at age 8 after witnessing his enraged mother set fire to his father, causing his death, he was taken in by auC paramilitaries… ”they told me they would always protect me. later bad things happened. i saw them kill people, a lot of people. they told me they had to. i didn’t like it. Sometimes I felt so angry i wanted to kill someone, but then i would feel afraid… one day the army came. they saw how small i was, and they captured me and brought me here… ”

“Cindy paula,” 17, a single mother working in the red light district, left home at 14 after her stepfather abused her. a drug addict living on the streets, she survived an overdose and decided to quit drugs, but she had few work options. “even though i know it’s not the best, for me it is the only way to get ahead. as a servant i’d make 300 quet- zales ($37 monthly). in a textile factory i’d make 1200 quetzales ($148 monthly). here i can make twice as much. but someday i hope i can leave here.”

Mariela hopes that one day the truth about her husband’s assassination will be known. Josué Giraldo Cardona, president of the Civic human rights Committee of meta, was gunned down oct. 13,1996 as he walked home with his small daughters. “everything about my husband’s life and work was transparent. his death remains shrouded in darkness… he deserves that the circumstances of his death be investigated and acknowledged transparently.

“Carolina,” 18, lives in a home for demobilized combatants sponsored by the Colombian Family Welfare institute. Carolina, then 15 and a small band of survivors from her FarC guerrilla unit, tried to get back to their base camp after combat with the Colom- bian army. on the way she stepped on a landmine losing her foot. “i cried and cried for three days without stopping… they kept me in the camp for a while, but they couldn’t keep carrying me… i had an aunt that they trusted, and they brought me to her… my aunt got afraid because of the smell [it was gangrenous], and so this is how my family decided to turn me in to the army. ever since then i’ve lived in a group home with three other girls who also used to be guerrillas… the FarC was my family for many years. but i don’t believe what they believe anymore. What good is the war? my friends are dead, and look at me. Sometimes i still cry and think who will ever love me now. but i will get a prosthetic leg. When i learn to walk with it and wear pants, no one needs to know that i don’t have my foot.”

Donna DeCesare, an award-winning photojournalist, is most widely known for her groundbreaking coverage of the spread of Los Angeles gangs in Central America. Her latest project, published in essay form here, was supported by a 2005 Fulbright fellowship in Colombia. She joined the Executive Committee of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma in 2007 and remains on the faculty at the Journalism School at the University of Texas at Austin where she has been on the Advisory Board of the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas since 2003. Additional work by DeCesare can be seen at www.donnadecesare.com and at the soon to be launched site www.destinyschildren.org She can be reached via email at ddecesare@mail.utexas.edu.

Related Articles

Salvadoran Youth, Transnationalism’s Other Product

English + Español

A completely distraught junior high school teacher in the Washington DC area approached her assistant principal—a highly-educated white middle-class man—one morning for urgent…

Cuba on the Edge: Short Stories from the Island

If you want to read contemporary Cuban fiction and do not have access to the Spanish original, an increasing number of excellent translations will now allow you to become acquainted with…

Making A Difference: Literacy in Calca

Seated on the floor of their school house twenty attentive first grade eyes watch as Martha turns the pages and asks aloud about the fate of David a friendly llama…