Pre-Columbian Art at Dumbarton Oaks

A Collection and Its Study Program

Olmec Jaded Figure

In the spring of 1912, Robert Woods Bliss, a Harvard alumnus and U.S. Embassy Secretary in Paris, was taken by a friend to a shop on the Boulevard Raspail, where he saw, for the first time, artifacts from ancient Mexico. Within a year, he had purchased a remarkable object from the shop, a ten-inch-high figure of a standing man, carved from dark-green jadeite.

The story of the Pre-Columbian Studies program at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C., dates back to that purchase, which was the beginning of the Robert Woods Bliss Collection of the art of Latin America before the Spanish conquest.

That first acquisition was originally labeled “Aztec,” the last of a long series of Mexican cultures before the arrival of the Spaniards, but in 1939 was correctly declared “Olmec,” one of the earliest of the great Mexican civilizations, by Harvard anthropology professor Alfred Tozzer, an expert on the Maya culture in Mexico.

Pre-Columbian studies have developed greatly since 1912, and the Dumbarton Oaks center has played a role in this development, thanks to Bliss’s early interest and support.

After graduation from Harvard College in 1900, Bliss served in the civilian government established in Puerto Rico following the Spanish-American War. In 1903, he joined the Foreign Service with postings in Europe and later Argentina. He and his wife traveled to that post by going across the Isthmus of Panama and down the west coast of South America, then crossing the Andes on muleback. They did not see any Pre-Columbian art in these travels.

In 1920, the Blisses bought their home, Dumbarton Oaks, a historic house on the northern edge of Georgetown, built originally in 1801 on a land-grant property that once included most of Georgetown. Dumbarton Oaks is known to many people because it was lent to the State Department in 1944 for conversations leading to the creation of the United Nations. The house, now adapted to

scholarly and public-exhibition use, is still surrounded by hillside gardens, developed under the aegis of Mrs. Bliss.

The Blisses gave the property to Harvard in 1940, along with a collection of Byzantine art and library; Dumbarton Oaks became the Harvard-affiliated Center for Byzantine Studies. Bliss then began to collect Pre-Columbian art more seriously. He acquired small carvings of greenstone or shell, larger stone carvings and polychrome vases from Mexico and Central America, as well as gold objects from Mexico, Central America, Colombia, and Peru, and textiles from Peru. He had a good eye, as art historians like to say, and he knew the kind of thing he liked beautiful objects made from fine materials. He did not seek a range of archaeological examples; he wanted the special piece. He collected from an aesthetic point of view, and he was evidently the first to do so. Nelson Rockefeller began somewhat later to collect with a similar attitude. Both collections grew in a period of interest in “primitive” art, an interest initiated largely by painters and sculptors in the early years of the century.

Mr and Ms Bliss sit in the rose gardens of Dumbarton Oaks.

Knowledgeable and eminent people in the field gave Bliss advice. Tozzer, a classmate of Bliss’s and an early advisor, was a curator at the Peabody Museum. Samuel Lothrop, a later consultant, had similar roles at Harvard. Another consultant was Matthew Stirling, of the Smithsonian Institution, who had excavated Olmec sites. In addition to collecting, Bliss supported Peabody Museum projects, notably Lothrop’s excavations of an early site at Venado Beach in the Panama Canal Zone. Bliss also served as a trustee of the American Museum of Natural History and of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, both of which were active in Latin Amercan archaeology.

In the early years of Bliss’s collecting, Pre-Columbian objects were rarely displayed in art museums. They belonged to, and were exhibited in, anthropological and natural-history museums. From 1927 until about 1940, however, the Fogg Museum at Harvard did devote a gallery to Maya art from the Peabody Museum collections. In 1929, in Paris, the Louvre showed an exhibit of Pre-Columbian art under the auspices of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. An exhibit of Pre-Columbian objects at the Burlington Fine Arts Club, London, took place in 1930, the same year the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York displayed a show of Peruvian textiles. Three years later, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, showcased handsome Pre-Columbian objects, mostly lent by anthropological museums. In 1940, Bliss’ first acquisition, the Olmec figure, was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in “Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art,” and in “An Exhibition of Pre-Columbian Art” at the Fogg Museum. The aesthetic interest in this art had begun.

Bliss, wanting his collection displayed in an art museum, approached the National Gallery of Art, in Washington. Despite some skepticism, director David Finley and chief curator John Walker thought “that it might be an interesting experiment” to show the objects. In 1947, it was installed on extended loan, and it remained on exhibit at the Gallery until 1962. It must have been a successful experiment.

In the late 1950s, the Bliss objects came to my attention while I was assistant registrar at the Gallery. I had been painting fairly seriously, and I first became interested in the Bliss objects visually. The Gallery was primarily a place for paintings–as it still is–and, at that time, no one there was seriously interested in such a collection. Its care fell largely into my hands. Bliss continued to acquire, and he would bring objects to the Gallery that he had bought or was considering buying. They were kept in the Registrar’s storeroom until they might be put on exhibition. Bliss would call ahead and then come into the office, saying “I have a new temptation.” He would take an object from the pocket of his overcoat, or his chauffeur would follow him with a picnic basket, and some object of jade or gold would emerge.

In those days, little awareness existed of how something had come out of the country of origin or how long it had been out. Those questions were not asked, and few people were concerned with them. Bliss, however, never purchased anything in the country of origin. One of his objects, a small Aztec sculpture, carved from a jadelike stone and known as “the birth goddess,” had reportedly been brought to Europe from Mexico City by one of Emperor Maximilian’s soldiers in the 1860s.

A tall, erect, immaculately groomed gentleman, Bliss had a delightful, slightly wicked sense of humor and a nice sense of humanity. He was appreciative and aware. When people are sometimes negligent about small civilities, I still recall a moment when I was wrapping a treasure of his, and, as I was about to tie a knot, Bliss put his finger on it to hold the string. A little thing, but not everyone does that or even notices the need.

Huari Mirror

The collection was left to Dumbarton Oaks on his death, where it joined the Byzantine center and the newly installed library of books on landscape architecture and the history of gardens, collected by Mrs. Bliss. The wing that would house the Pre-Columbian Collection, a “jewel box” designed by the noted architect Philip Johnson, was under construction when Bliss died in April 1962.

When John Thacher, the director of Dumbarton Oaks (another Harvard man, trained at the Fogg), asked me

to come set up the collection, I gladly did. Thacher, Smithsonian exhibition staff member James Mayo, and I worked on the installation, with approval from Johnson and assistance from Harvard-educated Michael Coe, a Yale anthropology faculty member. Coe was the invaluable advisor to the collection and, slightly later, to the scholarly program. The galleries were scheduled to open in the late fall of 1963, on a day that turned out to be shortly after the November 22 assassination of President Kennedy. The opening was much more subdued than it might have been.

Coe gave the first Pre-Columbian public lecture at Dumbarton Oaks, speaking about an Olmec greenstone carving in the collection, which had a later Maya incised text on the back. After the lecture, several people asked if it would be published. I spoke to Coe about the possibility of a Dumbarton Oaks publication, and he replied, “I’ll publish it, if it’s part of a series.” So, the publication program was born with the series “Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology.”

The first Dumbarton Oaks Pre-Columbian conference, “Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the Olmec,” in 1967 focused on the collection’s strong Olmec examples, with new information provided from field work by Coe and a University of California team. It was not until the 1960s that new Carbon-14 dating techniques proved how early Olmec was (c. 1500-300 B.C.). The publication of the conference the following year inaugurated a series of publications of annual conferences (now called symposia). The second conference and publication concerned Chavín, the Andean culture contemporaneous with the Olmec. New work was being done then by Peruvian archaeologists at Chavín’s major site.

A program of Pre-Columbian Fellows began in 1970, and their investigations led to further Dumbarton Oaks publications.

When we were setting up the Pre-Columbian program at Dumbarton Oaks, I felt strongly that we should generally follow Bliss’ taste and interests, that the main focus should always be the interpretation and study of the art of the great Pre-Columbian cultures. This was not simply to appreciate and honor his memory. Art history had been little used in Pre-Columbian archaeological studies at that time; George Kubler was virtually the only art historian in the field. The application of art-historical methods opened new pathways. Other approaches such as ethnography and the study of folklore were rarely used at that time to interpret archaeological material, but they have now become important resources in the field. I believed in using all possible methods, as long as the art that Bliss had cherished as art since 1912 should always be the highlighted center of study. I liked to think that he would approve of what we were doing.

Maya Jaiana Figure.

In the 1960s, Mrs. Bliss, a woman of delicate good looks and a perceptive manner, still lived in Georgetown and came often to Dumbarton Oaks, spending most of her time there in her beloved Garden Library. She was careful not to interfere with the workings of Dumbarton Oaks, but we–Thacher, Coe, and I– consulted her about many things. She, too, had a good eye and, although she had not previously expressed interest in the Pre-Columbian collection, she could look at objects with perception, and she was responsive to projects that we wanted to undertake.

I had come to Dumbarton Oaks to stay only temporarily, but it was a very alluring world, and it was exciting to be curator of the collection and to set up the programs and develop them. It was exciting, too, to see changes in the field, which had come about, in part, because of the attitudes and activities of the program. I stayed at Dumbarton Oaks for nearly 18 years, during a period of change, growth, and transition, when there was a growing focus on Pre-Columbian objects as art.

Winter/Spring 2001

Elizabeth P. Benson still works on Pre-Columbian art projects including the organization and catalogue of “Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico,” an exhibition held at the National Gallery of Art in 1996.

Related Articles

Guatemala Diary

In a deeply personal way, I feel like I am home again. Of all the places I have visited, Guatemala is the country I love and feel closest to. Certainly the most impressive aspect is the persevering Mayan people, who endured a 30-year civil war…

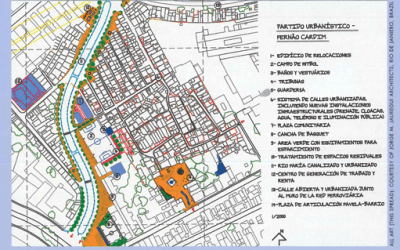

From Favela to Bairro

The Brazilian firm of Jorge Mario J¡uregui Architects is the first Latin American recipient of the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Veronica Rudge Green Award in Urban Design. The award…

Exploring New Horizons in Latin American Contemporary Art

When I first traveled to Peru by boat with my family fifty years ago, the country seemed as far away from Argentina as Boston from Buenos Aires. My husband had been sent there by W.R…