Productive Workers for the Nation

Architects, Peasants and Development in 1950s Colombia

In 1954, Colombian architect Alberto Valencia took a short trip to the small town of Anolaima, two hours away from Bogotá. An architect at the Inter-American Housing Center—a joint project of the Organization of American States and the U.S. Office for International Development—Valencia was excited to arrive in a “remote but attractive place” where he could find the “reality of life.”

After some days in the field, Valencia resolved to leave his books and city behind. Instead, he would return to Anolaima to teach peasants “how to build [new] houses…how to build homes…how to live in community.” He wanted to know the “Colombian peasants in person…their families…their lives…their souls, their activities.” Above all he wanted to transform those peasants into “modern citizens of the Colombian nation” (quotations from Housing Center Archive, Alberto Valencia’s personal archive).

Valencia’s preoccupations and desires speak eloquently of the new roles architects and other middle-class professionals began to play in political discussions about “development” and “modernity” in post-war Colombia. As the world split into the conflicting camps of the Cold War era, state institutions and multilateral development agencies, among them U.S. foreign aid organizations, constantly discussed how the social sciences could be applied in a practical manner to creating critical roles for professions such as architecture in achieving modernization. The goal was to move Latin America away from underdevelopment, political instability and social poverty, lifting it into what was conceived as a modern, developed, stable and democratic society.

In Colombia, policy makers, politicians, diplomats and intellectuals agreed that a new “mission” for professions such as architecture was imperative to bring La Violencia, a ten-year bloody conflict between Liberals and Conservatives, to a definitive end. Alberto Lleras Camargo (1958-1962) and Guillermo León Valencia (1962-1966), the two first presidents of the National Front, a 16-year power-sharing agreement between Liberals and Conservatives, wanted these new professionals to educate the working and peasant classes about how to live harmoniously and peacefully. These experiences, according to many politicians and intellectuals of the time, were foreign to the lives of Colombian citizens.

It is in this context that Alberto Valencia’s preoccupations and desires make so much sense. He, as an architect, was experiencing a new role assigned to architecture as a social science. He was only one among many professionals who were hired by the Colombian state to carry out what was understood as the crucial task of the 20th century: to bring “social progress,” “modernity,” and “peace” to those who had suffered the consequences of La Violencia. But in order to succeed in such a difficult endeavor it was necessary to train new generations of architects. During the late 1950s and 1960s, the Inter-American Housing Center, the Instituto de Crédito Territorial (the main state housing agency), the National University and a group of private elite organizations worked together to implement a training program to educate a new generation of architects committed to the national common good, rather than elite material interests. Much of this training was sponsored by the Kennedy-inspired U.S. Alliance for Progress, which founded or supported technical centers, vocational schools and universities. This training would allow a new generation of architects to perform what was conceived as a more democratic role: they would be ready to teach Colombia’s rural peasantry how to overcome poverty, political passivity, violent tendencies, underdevelopment and backwardness.

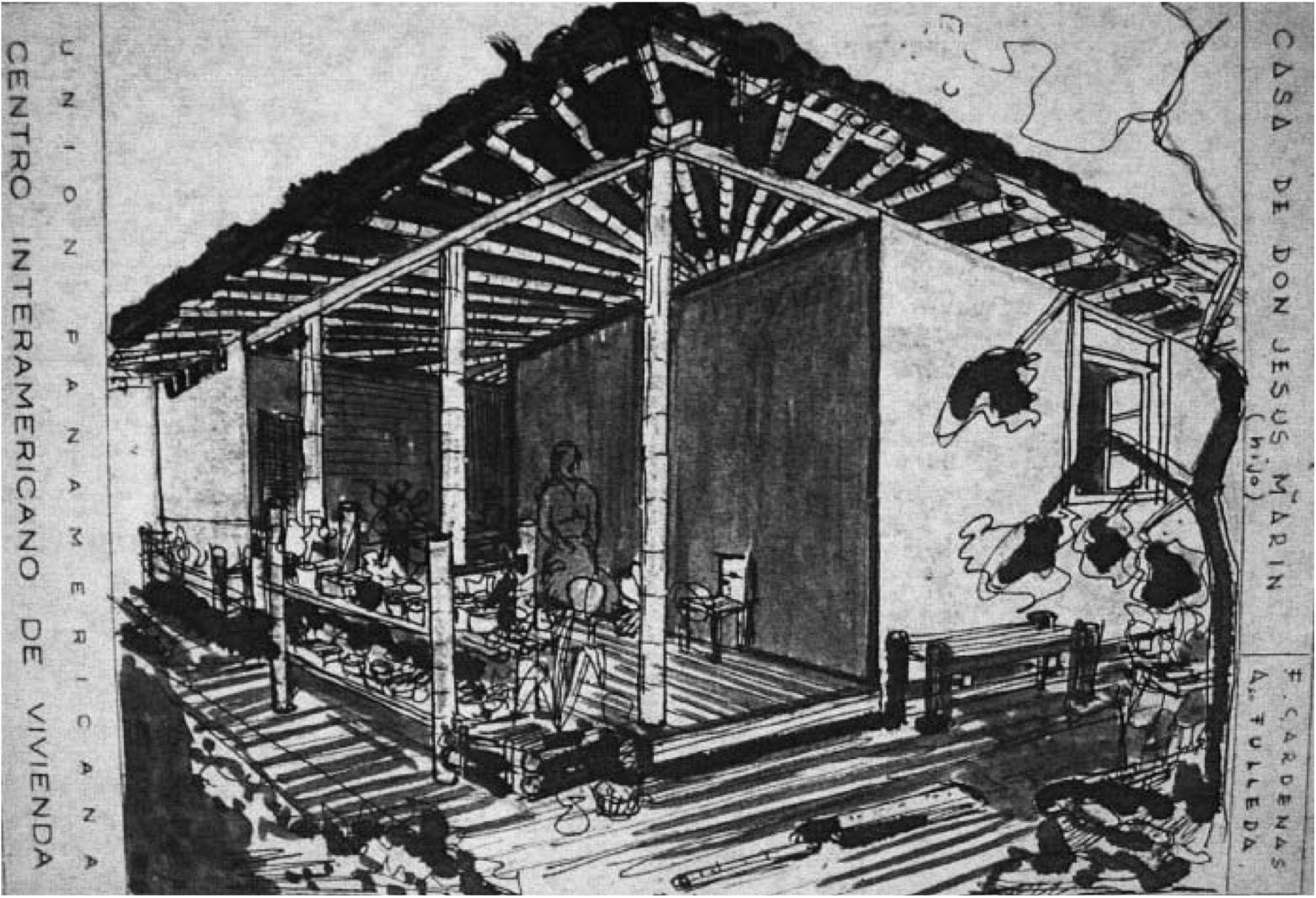

Alberto Valencia’s story as a modern architect offers an insightful example on how these new professionals roles assigned to architecture worked out in practice. In one of the many reports he filed for the Inter-American Housing Center, Valencia pondered the major causes of peasants’ underdevelopment and low productivity. For him, these problems resulted in part from the disorganization of peasants’ houses, which had merely two corridors surrounding a large physical space divided into simple and tedious sub-spaces. Peasants, he argued, had houses, but lacked homes. Usually generalizing from his extensive field work in Anolaima, Valencia presented peasants’ houses as having a rudimentary, if underdeveloped, architectural planning. With a certain sense of frustration, he constantly described peasants’ houses as monotonous, repetitive, and boring. In peasants’ houses, he observed, living rooms were simultaneously bedrooms; kitchens were often used for cultivating food or keeping animals. Even worse, he reported, there was no intimacy—children and parents usually slept in the same rooms. This promiscuity of space, as Valencia suggestively termed it, did not allow peasants to have homes where they could rest their bodies and cultivate their spirits—which would make them truly productive workers for the nation.

For Valencia, “proper division” of peasant houses corresponded with gender roles. He, along with many other architects and social scientists, wanted to educate male peasants on becoming good fathers, good breadwinners and, above all, good workers, not just good house owners. If a male peasant were to become a productive worker, he would need to have a specific room to sleep in (a space to recharge the necessary energy for the next day’s work), an intimate room to “reproduce,” and a living room in which to spend quality time with his children and wife. Only then could peasant men be simultaneously transformed into good fathers, husbands, and productive workers.

Peasant women would prepare and properly arrange the space of the house for the needs of the productive male worker. Wives would ensure the cleanliness of the home, the nutrition of the family, the moral rectitude of the children, and, above all, the harmony and coordination of the different spaces of the house. In doing so, it was argued, peasant women would become truly good mothers and wives who could prepare the house for their husbands, thus contributing to the creation of a new productive nation.

Architects, therefore, were seen as those who could “save” the peasants from ignorance, ill-health and low productivity by using their professional knowledge to build homes, rather than merely houses, allowing peasants to become productive workers for the nation. In particular, new gender-specific collective responsibilities were at the very center of how architects envisioned a new developed and modern society during this period.

Peasant men and women, however, would attach new meanings to the experiences of development and modernity—meanings that perhaps were foreseen neither by multilateral development programs nor professionals such as Alberto Valencia. Particularly, peasant men constantly complained that although they were very enthusiastic about being the head of the household and the workers of the nation, these new roles were not reflecting any economic benefit; indeed, if their material well-being was not met they could neither become good husbands/fathers nor true national productive workers. Peasant men reclaimed this possibility for material improvement by assuming that “their” wives and children should show respect, support and obedience as a condition for national productivity. Peasant women, however, understood these new gender assignments as a process through which these new, and “good” husbands, should give more independence, autonomy and opportunities to their wives in matters of how to run the home; some peasant women argued that if there was no material compensation to sustain the family, they could work outside the house to create the necessary conditions for that house to become a productive home. Thus, it was now peasant women, not men, who could bring modernity, progress and productivity to the Colombian society.

These appropriations questioned the role assigned to architects as the modernizers of the nation since, professionals such as Alberto Valencia complained, the productive (male) workers of the nation were nowhere to be seen. Valencia argued that peasant women (not men) were creating an obstacle—a “conflicted environment”—for the peasant house to become a home of a productive nation precisely because they were not following their assigned role as wives and mothers; peasants’ houses were only houses where husbands and wives were fighting for economic roles and the specific benefits attached to those roles. This “conflicted environment” did not provide the tranquility and harmony necessary for the male worker to produce for the nation. But if Valencia was not able to transform these male peasants into productive workers, his job as a professional was at stake; above all, he was not complying with his putative democratic role: to move the rural peasantry away from underdevelopment and backwardness and lift them into what he considered modern, developed and productive society. In this tension, the new role assigned to professional architects such as Alberto Valencia was perpetually in the making.

Spring | Summer 2010, Volume IX, Number 2

Ricardo López-Pedreros is an Assistant Professor of History at Western Washington University. He is currently working on a book monograph entitled A Beautiful Class. An Irresistible Democracy: The Transnational Formation of the Middle Class in Colombia, 1950-1974.

Related Articles

Architecture: Editor’s Letter

For years, readers have been commenting on the printed edition of ReVista: “How beautiful!” Now here’s a website to match, thanks to the efforts of the design firm 2communiqué and Kit Barron of DRCLAS. It’s not only a question of reflecting the aesthetics of the printed…

Working in the Antipodes

I was asked by ReVista to write an article on my own work, specifically about the fact that I do simultaneous work on social housing and high-profile architectural projects, something that is, to…

Three Tall Buildings

I used to hate the three tall towers that thrust against the verdant mountains. I used to think that the red brick towers dug into the landscape, belonging to some other city and some other space, created a scar of modernity…