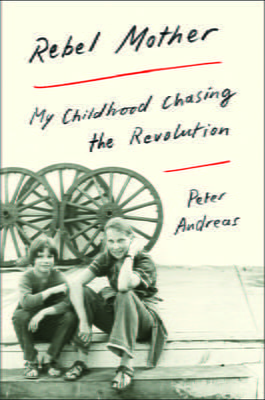

Rebel Mother: My Childhood Chasing the Revolution

A Quixotic Quest

At various points in Peter Andreas’ extraordinary childhood, he was kidnapped by his own mother, lived as a squatter in a commune in Chile during the tumultuous months leading up to the coup d’état in 1973, and traveled throughout Peru performing revolutionary street theater with his mother’s much-younger lover. Between the ages of 5 and 11, Andreas was shuttled back and forth from the United States to Latin America, from suburbs to slums, from stability to uncertainty, all in the midst of a complex custody battle between his parents.

Now John Hay Professor of International Studies at Brown University and author of nine academic books, Andreas concedes that his childhood adventures made him more attune to Latin American issues. Thirteen years after his mother passed away, Andreas has penned this compelling memoir reflecting an unconditional acceptance of his mother’s actions that defines the parent-child relationship in the early years of childhood. Despite that compassion, it’s clear throughout the book that Andreas has done a good deal of self-reflection to understand the limitations that all parents face when grappling with decisions about their own lives and aspirations vis-à-vis their children’s, which will surely be to the advantage of his own two young children.

Peter’s mother, Carol Andreas, underwent a personal metamorphosis in three parts: from suburban Mennonite mother-of-three to socialist university professor to starry-eyed chaser of political hotspots and, inevitably, of their corresponding revolutionaries. While perhaps more commonplace among the flower-power generation of the 1960s and 70s, today it takes a stretch of imagination to understand why a mother would choose to bring her youngest son on a nomadic and Quixotic quest through Chile, Argentina, and Peru, clamoring for revolution and uprising. In fact it’s quite the opposite of today’s typical migrant’s north-bound path in search of stability and security.

Following Carol’s death in 2004, Peter found a treasure trove of her diaries and letters, rendering focus to blurry memories, and attaching names, dates and places to the many characters and locales he and his mother encountered on their adventures. Even after returning to the United States, Carol remained a staunch Marxist and the two grew apart later in life, both personally and ideologically.

In the early 1970s Carol was, at age 40, a feminist university professor and activist who longed to be part of a socialist revolution. After moving Peter and his two older brothers to live in a commune in Berkeley, she eventually realized that by being surrounded only by like-minded people, she would not have the impact that she sought. To really be in the heart of the action, she took Peter to South America. Their first stop was the slums of Guayaquil where he was plagued by lice and had to quickly learn to speak Spanish. This marked the beginning of Peter and Carol’s Latin American adventure, with Peter in and out of formal schooling, usually below grade level on reading and writing even in English, and often left to his own devices or caring for his mother who had frequent bouts of sickness. Meanwhile, his father fought hard to keep Peter safe at home in suburban America, and his love for his son and frustration with the situation is heart-breaking at times.

Typical of the traveling duo’s dynamic, in July 1973, Carol left Peter with a family on a farm in Renaico, in southern Chile, to do research for an academic book. (Later her recollections of this time were published as a memoir, called Nothing Is as It Should Be: A North American Woman in Chile, the title of which might be a good description of the childhood that Peter writes about decades later in this volume.) He describes his time on the farm with the other children and the animals in those freezing and pristine winter months as one of the happiest times of his childhood. And yet, a few months later on September 11th Peter huddled around the radio with the rest of his foster family, listening intently as Salvador Allende addressed the Chilean people from La Moneda for the last time. Within a few hours Allende was dead, and Carol was incommunicado, only turning up a couple of weeks later. In the interim, 8-year-old Peter wondered: Had his mother been detained? Tortured? Disappeared? Would his father have a way to find him? Would he live on the farm forever? Even this experience, which would traumatize many children, was taken in stride as Peter and Carol, undeterred by Pinochet’s violent coup d’état, picked up their bags and moved on in search of revolution once again, this time in Buenos Aires. Was Carol right to leave Peter on a farm with near-strangers in a foreign, politically unstable country to pursue her own research while his father would have loved to have him at home with him in suburban Michigan? The answer to this question, in this particular case, is that there is no right answer.

To what extent should a mother suppress her own personal and political desires, her need for professional self-realization and sexual adventure, her fervor to be part of political action and social change even at the expense of her own life or her child’s? As a mother of children of about the age of young-Peter, and sharing Carol’s wanderlust, I grappled with these questions as I read one heart-wrenching and surprising tale after another. In Peter’s mind—both as a boy and now—there is never any doubt in Carol’s absolute conviction that by dragging her young son around with her, she was making a choice to reconcile her unwillingness to abandon her children with her aspirations of being involved in revolutionary causes. In Peter and Carol’s shared view, the unique exposure to hardship that Peter would face and the transitory nature of his childhood’s physical backdrop would be nothing but character-building. At the same time that Carol was able to pursue her own dreams, some journal entries reveal moments of self-doubt, and expressions of remorse about a falling out with Peter’s older brother, or fear over being considered a “BAD MOTHER” (her caps). Even years later, Carol acknowledged that she was still unresolved about her identity and her role in the world. A 1980 entry from her journal is telling:

The truth is that I am not a North American woman or Latin American nor European nor Asian. I’m a woman of the world trapped in Denver. Waiting. Waiting. Waiting. Waiting for the economic crisis. Waiting for total repression. Waiting for the definitive encounter. Waiting for the revolution in Peru. Waiting for Peter to become an adult. Waiting for the birth of the Revolutionary Organization of the Women of the World.

This universal ennui resonates today, and not just for mothers. It’s relatable for anyone tethered to a place or situation dictated by personal circumstances or geopolitics or one’s own spiritual or professional evolution. While reading about his father’s desperate custody battle, and his brothers’ independence—one brother even backpacking through South America on his own for months, barely fifteen years old—I was curious about the perspective of these other family members, though Andreas does an effective job invoking them and representing their feelings in an objective light. The descriptive passages of the book bring us into the space that the two protagonists inhabited— usually together, always temporarily. The book would make a beautiful film and is an interesting commentary about the political situation in Latin America at the time and the role that North American civilians such as Carol play when they are drawn toward revolutionary causes overseas. At the same time, it is a moving mother-son love story about sacrifices and impossible decisions that multi-faceted adult women face when they are unwilling to succumb to convention or to subjugate their own aspirations, however far-flung they may be.

Fall 2017, Volume XVII, Number 1

Erin Goodman is associate director of academic programs at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies. Her translation of Chilean minister Sergio Bitar’s memoir, titled Prisoner of Pinochet: My Year in a Chilean Concentration Camp (in Spanish, Dawson Isla 10) will be out this fall from University of Wisconsin Press. Erin enjoys traveling to Latin America whenever possible, with or without her two children.

Related Articles

A Review of Born in Blood and Fire

The fourth edition of Born in Blood and Fire is a concise yet comprehensive account of the intriguing history of Latin America and will be followed this year by a fifth edition.

A Review of El populismo en América Latina. La pieza que falta para comprender un fenómeno global

In 1946, during a campaign event in Argentina, then-candidate for president Juan Domingo Perón formulated a slogan, “Braden or Perón,” with which he could effectively discredit his opponents and position himself as a defender of national dignity against a foreign power.

A Review of Aaron Copland in Latin America: Music and Cultural Politics

In Aaron Copland in Latin America: Music and Cultural Politics, Carol Hess provides a nuanced exploration of the Brooklyn-born composer and conductor Aaron Copland (1900–1990), who served as a cultural diplomat in Latin America during multiple tours.