Reclaiming their Indigenous Languages

Female University Students’ Experiences

Grendy Isabel Nina Huaycane, who comes from the southern Peruvian Andean region of Puno, grew up in an urban area of Puno, where she heard both Spanish and Aymara, though she remembers that most of her interactions where “only in Spanish.” Her entrance to university was a turning point in her life.

Through various courses and exchanges with teachers and classmates, she tells us that “it was only at university that I began to connect with my territory, my language, my culture.” Like her, other young people who have not had the opportunity to learn to speak fluently or on a daily basis the Indigenous languages used by their families are studying to become future intercultural bilingual education (IBE) teachers.

In recent years, through the state scholarship Beca 18, young people with limited economic resources and high academic achievement have gained access to higher education in various cities of Peru. Unlike their peers who grew up as bilingual speakers, their entrance to university and to the IBE career marks a unique milestone in their lives. It is in this space where they not only develop their proficiency in their Indigenous languages, but more significantly, it is where they claim their right to recognize themselves as speakers of these languages, part of their family and community heritage.

The access of Indigenous students to higher education has increased in recent years in Peru and Latin America. However, this student diversity is not necessarily reflected in university policies, curricula and interactions, which are marked by various types of coloniality – that is, by logics that privilege Eurocentric understandings of knowledge, language and ways of being over others. Youth with trajectories different than those favored tend to experience different types of inequalities, although not in a passive manner (see contributions by Patricia Ames and Yuliana Kenfield). Higher education IBE programs can be spaces where these colonial logics are challenged and where intercultural attitudes and practices are encouraged. However, they can also be spaces where certain identities and ways of using language are valued over others. For example, the ideal student is often considered to be a bilingual individual who enters with an advanced oral command of the Indigenous language and knowledge of certain practices grounded on rural lived experiences. Little is known about how those who do not fit this profile experience the educational process.

Together with Angelica Choque Coaquira, Grendy Nina Huaycane, Guisell Quispe Cáceres and Victoria Charca Mamani, who were my students in 2018-2021, we set out to research the linguistic and cultural strengthening experiences of themselves and their peers from a biographical perspective. New speakers of Aymara, Quechua Kañaris and Quechua Chanka participated in our research. The academic concept of “new speakers” refers to individuals who learned to speak a language after their initial home socialization, usually as adults and in educational settings. In contexts of linguistic revitalization, new speaker research aims to make visible the experiences of individuals with language acquisition profiles different from those of speakers of an Indigenous language as their first language. Based on the collective dialogue that emerged during the research process, I reflect on how these new speakers experience reclaiming their Indigenous languages and what we can learn from them.

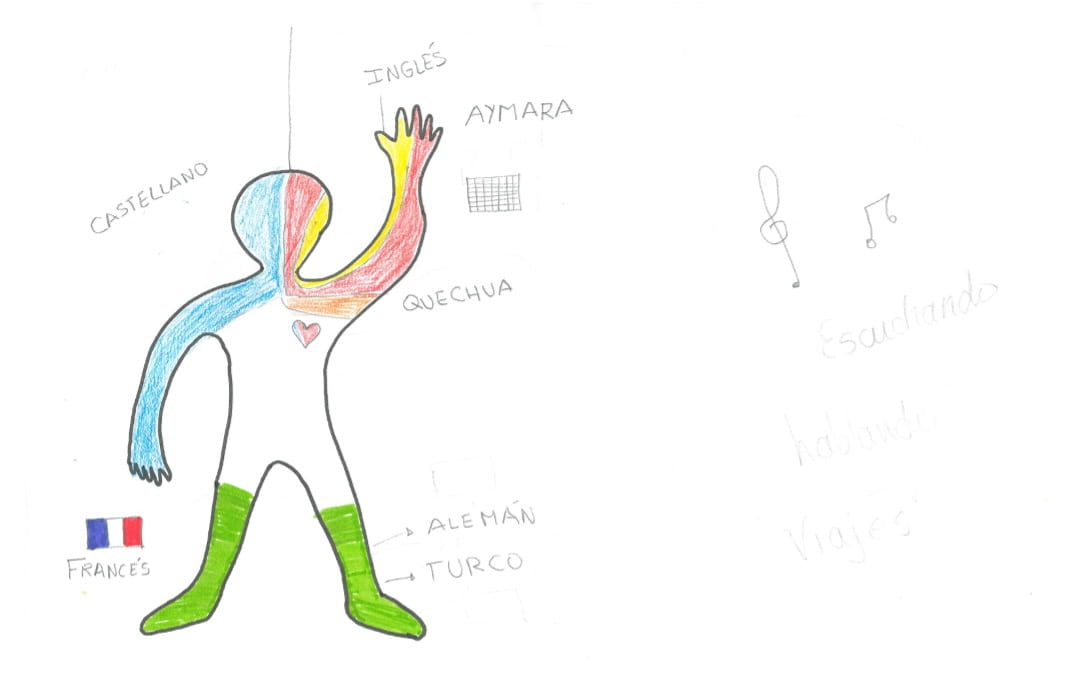

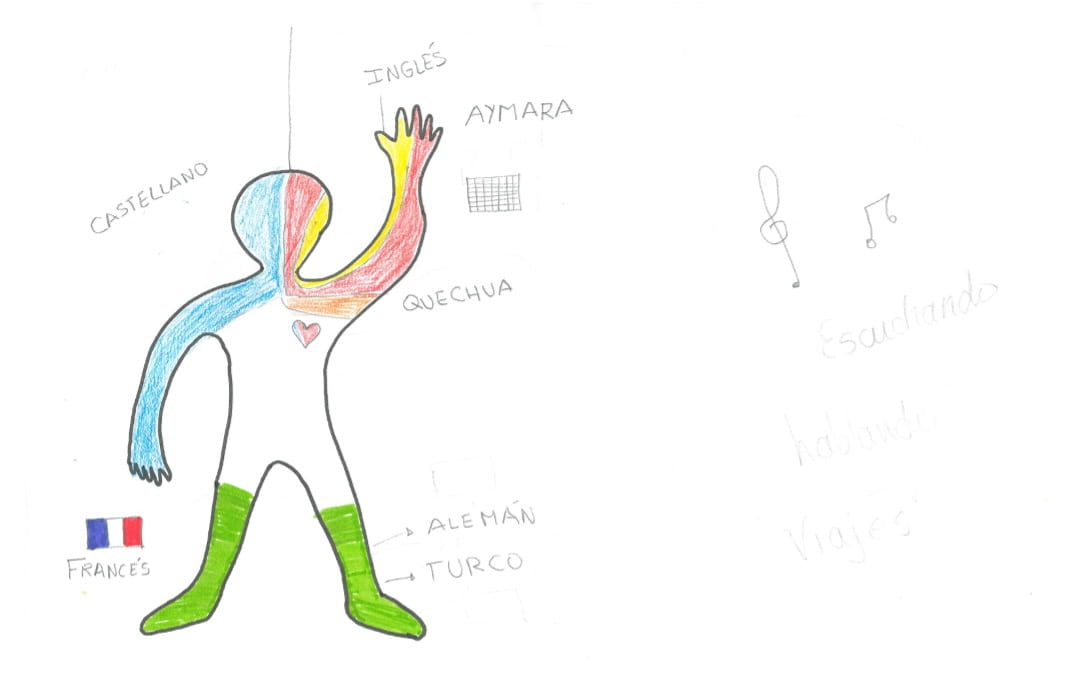

Crafting collective identities and belonging

During our research workshops, we asked participants they make their language portrait representing all the languages and ways of communicating important to them, and to tell us what and how they had done it (See Photo 1). This activity has been used in other multilingual contexts to make visible lived experiences of language that we cannot understand through observation alone. Grendy used the red color to represent Aymara and light blue for Spanish (see Figure 1). In her drawing, Spanish covers half of her head and one of her arms. Although the light blue color has no meaning, the greater proportion of Spanish was due to the fact that it is the language in which she speaks and writes the most. She represented Aymara with the red color, “because of the feeling, the affection”, and with a greater spatial presence in her heart (See Figure 1). Her university experience allowed her to learn more about herself, to reflect on the value of her Indigenous language and to recognize herself as Aymara. Grendy highlighted the importance of knowing the history of the Aymara people, the resilience with which they responded to multiple forms of violence, their capacity for transformation and wisdom. She also explained to us that one of her motivations to make her language flourish is her desire to communicate with Aymara speakers holders of different cultural knowledge. Grendy’s testimony and self-portrait reminds us that the mastery or degree of fluency in a language does not necessarily correspond to the identity, epistemic and affective bond that new speakers have with this language.

Figure 1 – Grendy’s language self-portrait.

Photo 1 – Sharing language self-portraits

Esperanza grew up in a multilingual Quechua-Aymara-Spanish home in Puno. She decided to represent herself as “an Aymara and Quechua woman and a modern woman as well.” She drew herself with two braids, wearing a sweater and a red pollera skirt, and wearing ojotas in her feet (See Figure 2). During the research workshops, Esperanza wore her hair short and often wore a T-shirt, jeans and sneakers. These styles are not contradictory; neither is her experience of being in the process of learning to speak Aymara, understanding Quechua, interacting in multiple spaces in Spanish and wishing to learn another Indigenous language such as Shipibo along with British English. Similar to her mother, she wants to be trilingual, “I want to say ‘hey I can speak to you in Quechua and also in Aymara,’ and it sounds nice like an empowered woman”. Her linguistic and cultural reclamation is also a gendered experience.

In fact, several participants reflected on how various ascribed and embodied identities —being a girl, living in an urban area, having Indigenous heritage—impacted their opportunities to learn their Indigenous languages during their childhood. They agreed that, had they been boys, they would currently have more fluency in these languages. They identified how their male cousins, brothers and relatives tended to have more freedom of movement than they did, and participated with more frequency and greater capacity in agricultural and community activities where they were exposed to Aymara and Quechua languages.

Nowadays, by recognizing themselves as women belonging to an Indigenous people, these young women are transforming various oppressions that have kept them away from their languages and are also questioning racist stereotypes. These stereotypes are not a thing of the past. At the beginning of the year, we witnessed in public televisionthe dehumanizing comments of the former minister of education of Perú against pollera-wearing women who were exercising their right to protest against the government. In contrast, by becoming an Aymara speaker, Esperanza seeks to honor her mother and her grandmother. Not only does she admire their multilingualism, but also their medicinal, child raising and weaving knowledge. For Esperanza, “the women of pollera, the knowledge they have, I kneel down [before them].”

Figure 2 – Esperanza’s language self-portrait

Although the students construct and give meaning, in different ways, to what it means to be an Indigenous woman today, they agree on the need to create spaces to “make visible the historical role of women” in their training program.

The paradoxes of reclaiming an Indigenous language

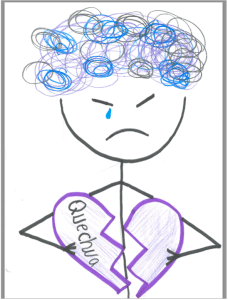

Reclaiming an Indigenous language can be empowering. Alejandra, who comes from a community of the Chanka Quechua people of the region of Apurimac, recalled how she began to encounter “our language”, which “maintains a cosmovision, a way of seeing the world that only we have” in Quechua classes. This was not only an intellectual realization, but an embodied experience, “I was learning it, but I was also feeling it, it was already like an emotion.”

At the same time, claiming back an Indigenous language can be a painful or silencing experience. For Alejandra, runasimi classes were “like two realities,” which she represented with two drawings (See Figure 3). On the one hand, “it increased my self-esteem” and, at the same time, “I also lowered my self-esteem … because of my slow learning.” She felt frustrated with herself, limited and truncated. The initial experience of Thalia F. Córdova Mamani, who comes from an Aymara family of the Moquegua region, was marked by enthusiasm. At the beginning, “I really wanted to learn in Aymara”. Later on, she recalls how a feeling of sadness and frustration took over, “it didn’t come out the way I wanted it to…no matter how hard I tried to pronounce it properly, I was frustrated because I couldn’t get it the way it was said…it didn’t come out naturally.”

Figure 3 – runasimi class according to Alejandra

The paradox of experiencing reclaiming an Indigenous language both as empowering and silencing is not unusual. According to linguist Pia Lane, new speakers of Indigenous languages often find themselves in precarious positions. Given the strong language-identity-people link, these speakers are often expected to embody this rootedness and to claim what they should already possess. In Esperanza’s case, this expectation leads her to wonder if she has the right to recognize herself as Aymara without yet having the language proficiency she desires, and to feel like “an incomplete Aymara.”

The ideal of the speaker who grew up speaking an Indigenous language as a referent causes discouragement and, at times, a sense of failure on the part of new speakers. They are certain that their learning needs and expectations are not the same as those of other classmates. For Alejandra, “Learning a language on the basis of another one is different from being born with it.” As Thalia sees it, “It’s not the same if your classmates already know and you don’t know.”. Not being able to participate or follow the classes is a cause of “frustration, there is also a lot of pressure, to a certain extent irritability”. Inside Indigenous language classes, the young women are sometimes afraid to ask teachers for support, believing it would reveal a lesser command of the language than is expected of them, or feel guilty about slowing down their more proficient classmates.

Recently, Indigenous researchers have explored the role that historical trauma can play in the learning experiences of those who engage in language reclamation. Ojibwe educator and researcher Mary Hermes suggests that learning an Indigenous language can act as a trigger for intergenerational trauma, reflected in feelings of wanting to give up or feeling stuck. Thalia, for example, described trying to speak Aymara with her grandparents, beyond greeting, as follows: “I can’t…in my mind I can’t, I try, but it doesn’t come out, it’s like a wall.” Some participants mentioned putting their learning on hold, questioning whether the problem resided within them, and blaming themselves for not being able to express themselves more fluently. For James McKenzie, Diné researcher, feelings of guilt, shame or anger at oneself for not speaking one’s language are also effects of historical wounds. For these reasons, he proposes that the teaching and learning of Indigenous languages should prioritize processes of healing and learners’ wellbeing.

Learning experiences are also embedded within institutional conditions. In the case of Quechua classes, they indicated that sometimes the variety of the language taught does not correspond to the one the university students are in the process of strengthening. Likewise, teaching methodologies do not recognize the learning needs of diverse groups, and the focus on teaching writing does not provide learners with sufficient opportunities to strengthen oral abilities, one of their main goals. Among their recommendations for improving the teacher education program, they propose “teaching by levels of mastery of the Indigenous languages,” teachers who not only know the language “but also know how to teach it” and “experiential teaching methods, not only theoretical ones.” The pressure to achieve the necessary communicative competencies to teach bilingually at the end of their careers, together with the reduced hours of formal teaching of Indigenous languages, present additional challenges.

“Yachay,” strategies, goals and dreams

The young women are aware that university education will not be enough to strengthen themselves as speakers, and they take on this goal in different ways. These include hiring private teachers, consulting dictionaries and other materials, enrolling in virtual classes, asking for support from classmates and family members, and using their languages in different spaces inside and outside the university. Gabriela Olortegui Artica, who comes from the Quechua people of the Huancavelica region, has combined university classes with other courses and workshops and strives to participate in community and family spaces where Quechua is used on a daily basis. Little by little, with patience, she is nearing her goal of communicating in Quechua as fluently as she does in Spanish. As for writing, although at the beginning it was a great challenge, “little by little, this challenge is instead becoming, little by little, in a way to express myself.”

For some young women, returning to their hometowns during the pandemic provided them with more opportunities to reestablish and strengthen intergenerational relationships not only through Spanish, but also through their Indigenous languages. For other new speakers, claiming back their languages transcends community and university spaces. Julissa, a member of the Kañaris Quechua people of Piura, has combined poetry and teaching Quechua in face-to-face and digital spaces. Among her dreams for the future is to continue developing fluency in her language “and at the same time teach the new generations … here in my town, in other places as well.” Like her, other students are empowering themselves as speakers and writers in their Indigenous languages to further reclaim it outside and inside the university.

Listening once again to their testimonies, more than a year after our research workshops, I observe the threads that run across shared, and also, diverse experiences. Their experiences remind me of something Gabriela shared with us in one of our last activities. Requested to choose a word that guided their future projections, Gabriela explained to us what yachay means to her: “I feel that learning is not only innate in us, but that we can, we have… the capacity to be able to direct it to our objectives, to those struggles that we have. Because it is necessary to hold close why we fight, with whom, for whom, and we do that through learning.”

In her appropriation of this Quechua concept, Gabriela emphasizes the relational and transformative nature of learning. Among the young women’s future goals, their desire for greater oral and written proficiency in their Indigenous languages is accompanied by a desire to continue learning and experiencing Quechua and Aymara knowledge to benefit their present and future students, to accompany youth and older community members in valuing their Indigenous languages and worldviews, and to exercise different leadership roles, as community leaders or in their professional activities for the benefit of their communities and society.

The experiences of these university students invite us to ask ourselves how language reclamation and revitalization projects recognize the diversity of identities, emotions and life histories that characterize those who are part of these projects. Learning from the experiences, reflections and proposals of this group of women is important for those of us who believe in the role that universities and other educational spaces play in creating more intercultural societies.

Some more photos of our research workshops:

Reivindicando sus lenguas originarias:

Las experiencias de mujeres universitarias

Por Frances Kvietok

Grendy Isabel Nina Huaycane, proveniente de la región surandina del Perú creció en un ambiente urbano de Puno, donde escuchaba el castellano y el aymara, aunque recuerda que casi todas sus interacciones eran “únicamente en castellano”. Su entrada a la universidad marcó un hito en su vida.

A través de distintos cursos e intercambios con docentes y compañeros, nos cuenta que “recién en la universidad empecé a vincularme con mi territorio, mi lengua, mi cultura”. Al igual que ella, otros jóvenes que no han tenido la oportunidad de aprender a hablar de manera fluida o cotidiana las lenguas originarias usadas por sus familiares se encuentran en proceso de formación universitaria como futuros docentes de educación intercultural bilingüe (EIB).

En los últimos años, a través de la beca estatal Beca 18, jóvenes con escasos recursos económicos y un alto rendimiento académico han accedido a estudios superiores en diversas ciudades del Perú. A diferencia de compañeros que crecieron como hablantes bilingües, la entrada a la universidad y a la carrera de EIB marca un antes y un después único en sus vidas. Es en este espacio donde no solo desarrollan su dominio lingüístico, pero más significativamente, reivindican su derecho a reconocerse como hablantes de sus lenguas originarias, parte de su herencia familiar y comunitaria.

El acceso de los estudiantes pertenecientes a pueblos originarios a la educación superior ha incrementado en los últimos años en Perú y Latinoamérica. Sin embargo, esta diversidad estudiantil no se ve necesariamente reflejada en las políticas, currículos e interacciones universitarias, marcadas por diversos tipos de colonialidad— es decir, por lógicas que favorecen posturas eurocéntricas del saber, del ser y del lenguaje por sobre otras. Los jóvenes con trayectorias distintas a las favorecidas suelen experimentar distintos tipos de desigualdades, aunque no de manera pasiva (Ver contribuciones de Patricia Ames y Yuliana Kenfield). Los programas de formación superior en EIB pueden constituirse en espacios donde se desafían estas lógicas coloniales y se apuestan por actitudes y prácticas interculturales. Sin embargo, también pueden ser espacios dónde se valoran ciertas identidades y maneras de usar el lenguaje por sobre otras. Por ejemplo, se suele tener como el ideal de estudiante al bilingüe que ingresa con un dominio oral avanzado en la lengua originaria y con conocimiento de ciertas prácticas basadas en vivencias rurales. Poco sabemos acerca de cómo aquellos que no encajan este perfil vivencian el proceso formativo.

Junto a Angelica Choque Coaquira, Grendy Nina Huaycane, Guisell Quispe Cáceres y Victoria Charca Mamani, quienes fueron mis estudiantes en 2018-2021, a comienzos del 2022 nos propusimos investigar las experiencias de fortalecimiento lingüístico y cultural de ellas y de sus compañeras desde una perspectiva biográfica. Dentro del grupo de investigación participaron nuevas hablantes del aymara, quechua kañaris y quechua chanka. El concepto académico de nuevos hablantes hace referencia a quienes aprendieron a hablar una lengua posterior a su socialización inicial, usualmente de adultos y en espacios escolarizados. En contextos de revitalización lingüística, busca visibilizar las experiencias de individuos con perfiles de adquisición lingüística distintos al de hablantes de una lengua originaria como primera lengua. En base al dialogar colectivo generado durante la investigación, reflexiono sobre cómo estas nuevas hablantes vivencian el proceso de reivindicar su lengua originaria y qué podemos aprender de ellas.

Construyendo identidades y pertenencias colectivas

Durante los encuentros de investigación, pedimos a las participantes realizar su autorretrato lingüístico donde representaran todas las lenguas y formas de comunicarse importantes para ellas, y nos contaran qué y cómo lo habían realizado (Ver Foto 1). Esta actividad ha sido usada en otros contextos multilingües para visibilizar experiencias vividas con el lenguaje que no siempre podemos comprender solo mediante la observación. Grendy usó el color rojo para representar al aymara y el celeste para el castellano (Ver Figura 1). En su dibujo, el castellano cubre la mitad de su cabeza y uno de sus brazos. Aunque el color celeste no guarda significado, la proporción mayor del castellano se debía a que es su lengua de mayor dominio oral y escrito. El aymara lo representó de color rojo, “por el sentimiento, cariño”, y con mayor presencia en su corazón (ver Figura 1). Su experiencia universitaria le permitió conocerse más a sí misma, reflexionar sobre el valor de su lengua originaria y a reconocerse como aymara. Grendy resaltó la importancia de conocer la historia del pueblo aymara, la resiliencia con la que respondió a múltiples violencias, su capacidad de transformación y su sabiduría. Además, nos explicó que su deseo de comunicarse con aymara-hablantes poseedoras de distintos saberes culturales es una motivación para hacer florecer su lengua. El testimonio y autorretrato de Grendy nos recuerda que el dominio o grado de fluidez en una lengua no corresponde necesariamente al vínculo identitario, epistémico y afectivo que las nuevas hablantes guardan con ella.

Figura 1: Autorretrato lingüístico de Grendy

Compartiendo los autorretratos lingüísticos

Esperanza creció en un hogar multilingüe quechua-aymara-castellano de Puno. Decidió representarse como “una mujer aymara, quechua y una mujer moderna también”. Se retrató con dos trenzas, vistiendo una chompa y una pollera roja, y calzando unas ojotas (Ver Figura 2). Durante los encuentros de investigación, Esperanza llevaba el pelo corto y solía vestir una polera, jeans y zapatillas. Estos estilos no son contradictorios; tampoco lo es su experiencia de encontrarse en proceso de aprender a hablar el aymara, comprender el quechua, desenvolverse en múltiples espacios en castellano y desear aprender otra lengua originaria como el shipibo junto al inglés británico. Al igual que su madre, desea ser trilingüe, “quiero decir ‘oye yo puedo hablarte en quechua y también en aymara,’ y suena bonito como una mujer empoderada”. Su reivindicación lingüística y cultural es también una experiencia de género.

De hecho, varias participantes reflexionaron sobre cómo las distintas identidades que traspasan y encarnan sus cuerpos – ser niña, vivir en una zona urbana, tener herencia originaria – afectaron sus oportunidades de aprender sus lenguas originarias en su infancia. Coincidieron que, si hubieran sido varones, tendrían más dominio de la lengua originaria en la actualidad. Identificaron como sus primos, hermanos y parientes hombres solían tener más libertad de movimiento que ellas y participaban en mayor medida en labores agrícolas y comunitarias donde estaban expuestos a la lengua originaria.

Hoy en día, al reconocerse como mujeres perteneciente a un pueblo originario, las jóvenes transforman distintas opresiones que las mantuvieron alejadas de sus lenguas y también cuestionan estereotipos racistas. Estos estereotipos no son cosa del pasado. A inicio del 2022, vivenciamos en televisión pública los comentarios deshumanizantes del exministro de educación del Perú contra mujeres de pollera que ejercían su derecho de protesta contra el gobierno. En contraste, al convertirse en hablante del aymara, Esperanza busca honrar a su madre y a su abuela. No solo admira su multilingüismo, pero también sus saberes medicinales, de crianza y del tejido. Para Esperanza, “las mujeres de pollera, el saber que tienen, yo me arrodillo”.

Si bien las estudiantes construyen y dan significado de diversas maneras a lo que significa ser una mujer perteneciente a un pueblo originario en la actualidad, concuerdan en la necesidad de crear espacios donde se logre “visibilizar el rol histórico de las mujeres” dentro de su programa de formación.

Figura 2 – Retrato lingüístico de Esperanza

Las paradojas de reivindicar una lengua originaria

El recuperar una lengua originaria puede ser empoderador. Alejandra, originaria de una comunidad del pueblo quechua chanka de la región de Apurímac, recordó como en las clases de quechua fue encontrándose con “nuestra lengua”, la cual “mantiene una cosmovisión, una manera de ver el mundo que solo nosotros tenemos”. Esta no fue solamente una realización intelectual, sino una experiencia encarnada, “lo estaba aprendiendo, pero también lo estaba sintiendo, ya era como una emoción”.

Al mismo tiempo, recuperar una lengua originaria puede ser una experiencia dolorosa o silenciadora. Para Alejandra, las clases de runasimi eran “como dos realidades”, las cuales representó con dos dibujos (Ver Figura 3). Por un lado, “incrementaba mi autoestima” y, al mismo tiempo, “también yo misma me bajaba el autoestima … por mi aprendizaje lento”. Se sentía frustrada consigo misma, limitada y truncada. La experiencia inicial de Thalia F. Córdova Mamani, proveniente de una familia aymara de la región de Moquegua, fue marcada por entusiasmo. Al inicio, “tenía muchas ganas de aprender en aymara”. Luego, recuerda que fue ganando un sentimiento de tristeza y frustración, “no me salió como yo quería…por más que yo trataba de pronunciarlo adecuadamente, me daba una frustración al no poder lograrlo cómo se decía…no me salía naturalmente”.

Figura 3 – la clase de runasimi según Alejandra

La paradoja de vivenciar la recuperación de una lengua originaria como empoderador y silenciador al mismo tiempo no es inusual. Según la lingüista Pia Lane, los nuevos hablantes de lenguas originarias suelen encontrarse en posiciones precarias. Dado el fuerte vínculo entre lengua-identidad-comunidad, muchas veces se espera que estos hablantes encarnen este arraigo y reivindiquen lo que ya deberían de poseer. En el caso de Esperanza, esta expectativa la lleva a preguntarse si tiene el derecho de reconocerse como aymara sin aun tener el dominio de la lengua que desea, y a sentirse como “una aymara incompleta”.

El ideal del hablante que creció hablando una lengua originaria como referente ocasiona desánimo y, a veces, una sensación de fracaso por parte de las nuevas hablantes. Ellas son certeras al identificar que sus necesidades y expectativas de aprendizaje no son las mismas que las de sus demás compañeros de aula. Para Alejandra, “aprender una lengua a partir de otra es distinto a nacer con ella”. Como lo ve Thalia, “no es lo mismo que tus compañeros ya sepan y tú no sepas”. El no poder participar o seguir las clases es causa de “frustración, hay una gran presión también, en cierta parte irritabilidad”. Dentro de las clases de lenguas originarias, las jóvenes a veces temen pedir apoyo a los docentes, pues revelaría un dominio de la lengua menor al que se espera de ellas, o sienten culpabilidad de retrasar a compañeros con mayor dominio.

Recientemente, distintos investigadores indígenas se han interesado por el rol que el trauma histórico puede tener en quienes recuperan su lengua. La investigadora y educadora ojibwe Mary Hermes sugiere que el reaprender una lengua indígena puede actuar como un desencadenante de traumas intergeneracionales, reflejado en sensaciones de querer renunciar o sentirse atascado. Thalia, por ejemplo, describió el tratar de hablar aymara con sus abuelos más allá del saludo de la siguiente manera: “no puedo…en mi mente no puedo, trato, pero no me sale, es como un muro”. Algunas participantes mencionaron poner en pausa su aprendizaje, cuestionarse si el problema residía dentro de ellas y culparse al no poder expresarse más fluidamente. Para James McKenzie, investigador del pueblo diné, los sentimientos de culpa, vergüenza o enojo contra uno mismo por no hablar su lengua también son efectos de heridas históricas. Por estas razones, propone que la enseñanza y aprendizaje de lenguas originarias priorice procesos de sanación y el bienestar de sus aprendices.

Las experiencias de aprendizaje también se enmarcan dentro de condiciones institucionales. En el caso de las clases de quechua, indicaron como a veces se enseña una variedad de la lengua que no corresponde a la que las jóvenes se encuentran en proceso de fortalecer. Asimismo, las metodologías de enseñanza no reconocen las necesidades de aprendizaje de grupos diversos, y el enfoque en la enseñanza de la escritura no les brinda suficientes oportunidades para fortalecer habilidades orales en sus lenguas originarias, una de sus mayores metas. Dentro de las recomendaciones para mejorar la propuesta formativa, ellas proponen una “enseñanza por niveles de dominio de las lenguas originarias”, docentes que no solo sepan la lengua “sino que sepan enseñarla” y “métodos de enseñanza vivenciales, no solo teóricos”. La presión de lograr las competencias comunicativas necesarias para enseñar de manera bilingüe al culminar su carrera, junto con las reducidas horas de enseñanza formal de la lengua originaria, presentan retos adicionales.

“Yachay,” estrategias, metas y sueños

Las jóvenes son conscientes de que la propuesta formativa universitaria no será suficiente para lograr fortalecerse como hablantes y asumen esta meta de maneras diversas. Entre ellas figuran contratar a profesores privados, consultar diccionarios y otros materiales, inscribirse en clases virtuales, pedir apoyo de compañeros y familiares y hacer uso de su lengua en distintos espacios fuera y dentro de la carrera. Gabriela Olortegui Artica, originaria del pueblo quechua de la región de Huancavelica, ha combinado las clases universitarias con otros cursos y talleres y se esfuerza por participar en espacios comunales y familiares donde se usa el quechua cotidianamente. Poco a poco, con paciencia, va acercándose a su meta comunicarse en quechua con la misma soltura que lo hace en castellano. En cuanto a la escritura, si bien al principio fue un gran reto, “poco a poco, ese reto más bien se va convirtiendo poco a poco en una facilidad de expresarme”.

Para algunas jóvenes, el retorno a sus comunidades de origen durante la pandemia les brindó más oportunidades para restablecer y fortalecer relaciones intergeneracionales ya no solo a través del castellano, pero también a través de sus lenguas originarias. Para otras nuevas hablantes, la recuperación de sus lenguas transciende el espacio comunal y universitario. Julissa, originaria del pueblo quechua kañaris de Piura, ha combinado la poesía y la enseñanza del quechua en espacios presenciales y digitales. Entre sus sueños a futuro rescata seguir desarrollando fluidez en su lengua “y a la vez enseñarles a las nuevas generaciones … aquí en mi pueblo, en otros lugares también.” Como ella, otras estudiantes se van empoderando como hablantes y escritoras en sus lenguas originarias para reivindicarla fuera y dentro la universidad.

Volviendo a escuchar sus testimonios, hace más de un año de nuestros encuentros de investigación, observo los hilos que atraviesan experiencias compartidas y, a la vez, diversas. Sus experiencias me hacen recordar algo que nos compartió Gabriela en uno de nuestros últimos diálogos. Invitadas a elegir una palabra que guie sus proyecciones a futuro, Gabriela nos explicó qué significa yachay para ella: “siento que el aprender no solamente es innato en nosotros, sino que también podemos, tenemos… la capacidad para poder dirigirlo a nuestros objetivos, a esas luchas que tenemos. Porque es necesario sustentar el por qué luchamos, con quienes, para quienes y eso lo hacemos a través del aprendizaje”.

En su apropiación de este concepto quechua, Gabriela enfatiza el carácter relacional y transformador del aprendizaje. Entre las metas a futuro de las jóvenes, sus deseos de mayor dominio oral y escrito en sus lenguas van acompañados de deseos de continuar aprendiendo y vivenciando saberes quechuas y aymaras con el propósito de beneficiar a sus presentes y futuros estudiantes, de acompañar a jóvenes, comuneros y comuneras a valorizar sus lenguas y cosmovisiones originarias, y de ejercer distintos roles de liderazgo, como lideresas comunales o ejerciendo sus profesiones y actividades en beneficio de sus comunidades de origen y de la sociedad en general.

Las experiencias de las universitarias nos invitan a preguntarnos cómo los proyectos de fortalecimiento y revitalización lingüística reconocen la diversidad de identidades, emociones e historias de vida que caracterizan a quienes son parte de estos proyectos. Aprender de las experiencias, reflexiones y propuestas de este grupo de universitarias es importante para quienes apostamos por el rol que las universidades y otros espacios educativos guardan para crear sociedades más interculturales.

Algunas fotos más de los talleres de investigación:

Frances Kvietok is Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center for Multilingualism in Society across the Lifespan of the University of Oslo. She researches, teaches and consults on bilingual education, language revitalization and qualitative research methodologies. The project she writes about has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101026813.

Frances Kvietok es investigadora posdoctoral MSCA en el Centro del Multilingüismo en la Sociedad a lo largo de la Vida de la Universidad de la Oslo. Se dedica a la investigación, enseñanza y consultoría en temas de educación bilingüe, revitalización lingüística y metodologías cualitativas.El proyecto sobre el que escribe ha recibido financiación del programa de investigación e innovación Horizonte 2020 de la Unión Europea en virtud del acuerdo de subvención Marie Sklodowska-Curie nº 101026813.

Related Articles

Unequal Beginnings: Artificial Intelligence and Latin America’s Educational Divide

Latin America has never lacked talent. What it has lacked, historically, structurally and persistently is equal access to the conditions that allow talent to flourish.

Financial Institutions: Strengthening the Rule of Law in Latin America

Latin American countries continue to accumulate laws, regulations and rules. These legal instruments need to be implemented and then enforced.

Extractivism and Colonialism in Argentina: A View from the Patagonia

It was snowing the day in early August when I arrived at Lof Pillan Mahuiza, a Mapuche-Tehuelche community around 60 miles from Esquel, the provincial capital of Chubut, Argentina.