Recreating Chican@ Enclaves

Photo courtesy of Arthur Valdez.

Centrally located between southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, is a hundred-mile long by seventy-mile wide intermountain basin known as the San Luis Valley. Surrounded on the east and the west by the two mountain ranges, the Rio Grande del Norte traverses down the middle of the elongated landmass I call home. By definition home is a place of security and refuge. In the wake of September 11th, like most Americans I have become preoccupied with global threats to my home. And yet, I cannot ignore important local issues. In this instance, I am concerned how change agents, like tourism, are influencing culture and religion in my hometown.

In 1851, the first permanent settlements in the San Luis Valley were established by mestizo pobladores from New Mexico’s Taos Valley; my husband and my ancestors were among this group. A decade later the Territory of Colorado usurped the far northern New Mexican uplands, including the San Luis Valley. This political slight-of-hand stranded several thousands Nuevo Mexicanos in a state that was hostile to Mexican Era land claims and intolerant of Indohispanos.

Initially established by Mexican land grants, Costilla County was among Colorado’s first 17 counties. During Colorado’s Territorial Period (1861-1876), urban newspapers like the Rocky Mountain News (RMN) used hispano-phobic imagery to justify legal rulings hostile to communal land grant traditions, while touting the mineral and agricultural potential of the county to gold miners, colonies of Midwest farmers, and urban emigrants looking to capitalize on resources in the former Mexican Republic. Counted among this group were journalists and travel writers.

The most notable journalist to arrive in the San Luis Valley was Charles Flecher Lummis on his way to California in 1884. As a correspondent for the Chillicothe Leader, Lummis wrote his impressions of what he defined as the “Southwest”. When Lummis stopped in Alamosa (the largest town in the Valley), he mailed a series of letters to his newspaper in Ohio. While his first letters were filled with diminutive slurs, within a few years Lummis radically altered his views. Since Lummis’s monographs and romantic novels popularize Pueblos and Indohispanos as exotic “Others,” he laid the groundwork for cultural tourism in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado.

I became interested in the role of tourism in transforming culture after attending a graduate seminar on Anthropology of Tourism taught by Dr. Sylvia Rodriguez at the University of New Mexico. Inspired by Rodriguez (who writes extensively on the impacts of amenity tourism in the Taos Valley), I now track how government-sponsored tourism is influencing the old Nuevo Mexicano enclaves in southern Colorado to become quaint and idyllic “sights.” Since I live on a farmstead within the Rio Culebra Basin my observations are focused on the southern villages of Costilla County including, the town of San Luis.

Well before cultural tourism made headway in Costilla County, San Luis was described as being “purely Mexican” in its “prevailing style of architecture and in the customs.” with “scenery rivaling…the Alps and other classic lands of the tourist and traveler.” In this context, members of a lay Catholic society known as La Sociedad de Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno, or Los Hermanos Penitentes, emerged as a tourist “sight.”

Formalized in New Mexico near the end of the eighteenth century, the cofradia, or brotherhood, replicated important religious ceremonies, and provided spiritual comfort and support to frontier communities in the absence of priests. Although the cofradia’s origins are murky, scholars speculate that the fraternity stems from the Third Order of St. Francis, a lay society introduced in New Mexico through the long tenure of the Franciscans. Because the cofradia flourished in watersheds and valleys, emerging near the end of the eighteenth century, the order expanded with the founding of Nuevo Mexicano’s settlements. Establishing moradas (places for prayer) in remote areas, los hermanos situated chapter houses to provide privacy as early penitential rituals included self-flagellation.

Privacy not only allowed the hermanos to perform ritual cleansing, it preserved group-solidarity and religious customs during American penetration. In the aftermath of American occupation, came unfounded rumors of human crucifixion during Semana Santa, or Holy Week. Ignorant of the mutual aid rendered by the cofradia, newly arriving foreign priests were scandalized. While priests attempted to control the cofradia, Protestant Missionaries focused on conversion of the leadership. In the San Luis Valley, the U.S. Army (based at the northern end of Costilla County) twice attempted to disrupt ceremonies in the 1860s. It is clear that race relations intersected with the brotherhood, as hermanos, who were Mexicano, were relegated to a subordinate position and driven underground.

Predictably, Charles Lummis helped to introduce the penitentes to American audiences late in the nineteenth century. Stereotyped in his embellished ethnographic accounts as radical fanatics, Lummis’s misinterpretations sensationalized penitential practices. Worse yet, are a series of photos he took in a remote New Mexican village in 1888. To capture the images of hermanos practicing their Lenten rituals, Lummis forcefully intruded, taking photos of flagellation and an alleged crucifixion with an armed guard at his side. These photos have forever stigmatized the brotherhood.

In Colorado, Reverend Alex Darley, a self-proclaimed “apostle of the Colorado Mexicans,” rehashed Loomis’s observations to make his case against Catholicism. Darley’s self-published books had a profound impact on the brotherhood in the San Luis Valley and in other Mexicano enclaves. By 1894, negative accounts of cofradia appeared in Valley newspapers. With journalistic prompting, thrill-seeking tourists commenced clandestine viewing of hermano rituals in the 1920s. Eventually this led to taunting and hostility. During the Great Depression, public interpretation softened and the Catholic Church recognized the brotherhood in 1947. Ironically, although Lummis and Darley wanted the brotherhood banned, their publications transformed them into an authentic medieval artifact. Darley foresaw this when he commented that, “Here are sights for strong-stomached tourists.”

Today, the hermandad, its moradas, and other valuable cultural imagery have been appropriated and packaged for tourism. This is not a new phenomenon. In the late 1960s, War on Poverty programs promoted heritage tourism in San Luis. Among other things, a master plan called for a tourism complex and convention center, and a historic recreation of the San Luis Plaza in the mode of Williamsburg. Because funding never manifested, the project failed.

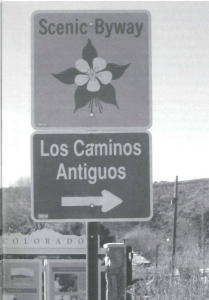

Since the 1990s, federal and state entities are reintroducing plans to make Costilla County into a designated heritage site. Because of the hermanos’ deep traditions, they have become an icon of religious tourism. Currently, a consortium of promoters has integrated the cofradia, into Caminos Antigos Byway. Designated in 1991 by the Colorado Transportation Commission, the 129-mile Byway is designed to guide visitors to several communities in the San Luis Valley. The year the Byway was inaugurated, a “conceptual prospectus” outlined a route “into the heart of the Spanish-Mexican villages of the Rio Culebra watershed.” Since a “Penitente morada” was located along the pathway, the hermanos were drawn into Caminos Antiguos orbit.

In an attempt to take tourists to “obscure areas,” Caminos Antiguos focused on “interpreting cultural heritage.” Initially a Master Plan designed the Byway as a self-guided route, using “lure brochures and a promotional video,” in conjunction with a series of kiosks and interpretive displays. As one of several “interpretive sites,” the morada was slated for a 36″ x 24″ low-profile “wayside exhibit” placed in close proximity to the structure, which is traditionally shuttered and closed to non-members.

By 1998, local organizers applied for Federal Highway Administration funding to expand the Byway. Always evolving, the new proposal called for thematic weekend tours of “Hispano Mission Churches in Costilla County.” Local interpreters and a guided visit to one morada was a part of the schedule. In a thinly veiled attempt to pretend that tourists would not intrude, the morada could only be viewed from the outside. However, since Caminos Antiguos focuses on cultural interpretation, the schedule promised “hermanos will be on hand to interpret the significance of the Penitentes.” In 2001, three spiritual retreats were incorporated into the tour; finally, visitors were able to hear prayers in Spanish and to listen to alabados, or hymns of los hermanos. The tourist fee included “experience” guides, logistics crew, meals, and over-night lodging. At this writing, tours and retreats never materialized. Local guides and logistic crews, who attended required hospitality training without any pay, are disappointed.

The marketing the rural village of southern Costilla County as a cultural artifact of Colorado’s “Mythic West” is a part of a larger trend to recreate Latina culture for mass consumption. Clearly, local support for heritage tourism comes from the promise of lasting economic prosperity. Regardless, the monolithic imagery of the local culture as a relic of the past contradicts reality. Time did not stand still in Costilla County; because we live in the 21st century, albeit in a rural setting, we are modern and diverse. Despite, the fact that those who do not directly benefit from the Byway have not consented to cultural interpretation, government-sponsored tourism continues to microscopically penetrate the community and groups like the hermanos without thought.

Since the hegemonic structure of tourism in the Southwest is complex, this story has gray areas. My husband and I have worked to document historic adobe structures in Costilla County for over a decade; our research is oriented to support land use planning we introduced in the 1990s. However, local Byway supporters have used writings and names without our knowledge. Since my husband Arnold is an active member of the hermandad, we are very concerned; after all the hermanos prayed and sung at my father’s wake in October. We know first hand that the hermanos help families to grieve and Lenten services are contemplative opportunities for improvement. Of course there are no secrets, after all the archive on the hermanos is voluminous and coffee table books abound. Still because “all” of the hermanos—like many other subjects of tourist curiosity–never consented to this project The Byway has marginalized the cofradia. If the Byway continues to promote the hermanos as subjects and their moradas as objects of curiosity, spirituality and privacy will be fractured by the intrusive nature of the Byway.

Winter 2002, Volume I, Number 2

Doctoral Candidate at the University of New Mexico, Department of American Studies, Maria Mondragon-Valdez is an activist working on Mexican land grants and local environmental issues. As co-founder of Valdez & Associates, Maria and her husband Arnold (a Loeb Fellow studying at Harvard in 2000), have researched and written on the architectural history of Costilla County for the past twelve years. Maria dedicates this piece to her father Charles Mondragon (1922-2001).

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Tourism

Ellen Schneider’s description of Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega in her provocative article on Nicaraguan democracy sent me scurrying to my oversized scrapbooks of newspaper articles. I wanted to show her that rather than being perceived as a caudillo

Tourist Photography’s Fictional Conquest

Recently, while walking across the Harvard campus, I was stopped by two tourists with a camera. They asked me if I would take a picture of them beside the words “HARVARD LAW SCHOOL,” …

Tourism’s Landscape of Knowledge

Tourism research and scholarship is a fairly new interdisciplinary field, and I hope to offer an abbreviated pastiche of this expanding field of knowledge, culled from my own experience….