Recycle the Classics

Pre-texts for High-order Thinking in Low-resourced Areas

Literature is recycled material, a pretext for making more art. I learned this distillation of lots of literary criticism in workshops with children. I also learned that creative and critical thinking are practically the same faculty, since both take a distance from found material and turn it into stuff for interpretation. For a teacher of literature over a long lifetime, these are embarrassingly basic lessons to be learning so late, but I report them here for anyone who wants to save time and stress.

My trainer was Milagros Saldarriaga, just out of college when she cofounded an artisanal publishing house named Sarita Cartonera for the childish and chaste patron saint of Andean migrants in Lima, Peru. This became one of the first of now more than 200 cardboard publishers throughout Latin America, with replications in Africa.

As far as I know, Sarita is the only one that developed a pedagogy along with publications. She had to. It was not enough to make beautiful and affordable books, inspired by the publishing house Eloísa Cartonera of Buenos Aires, if books were not in demand. Lima may have looked similar to distressed Buenos Aires, with its lack of money coupled with an abundance of good writers and poor paper pickers, but indifference to reading turned out to be an obstacle more stubborn than poverty. So Sarita began to use her products as prompts for producing more readers. What better way to use books!

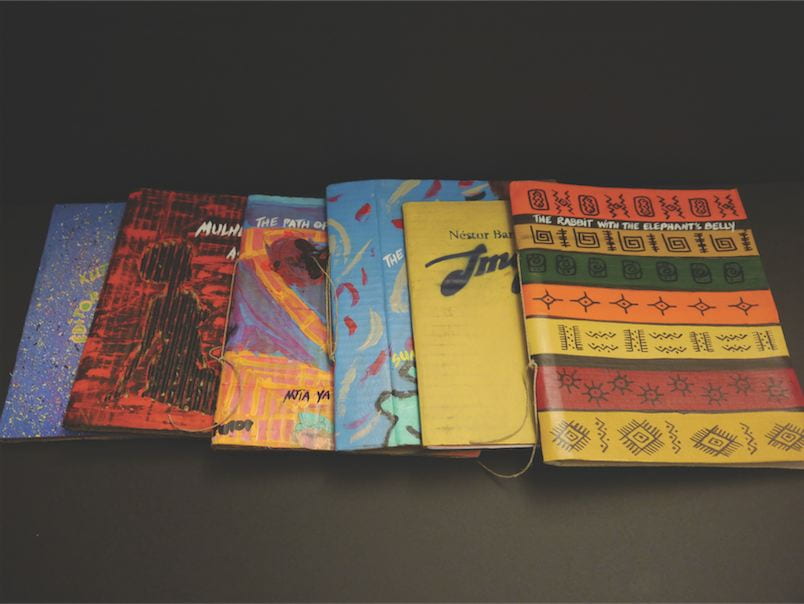

Even during the Argentine economic crash of 2001, haunting photographs show porteños staring into bookstores, longingly. Just a year after the economy fell apart and long before it recovered, Eloísa Cartonera was responding to the hunger for literature with an alternative to the failed book business. Poet Washington Cucurto and painter Javier Barilaro started to use and reuse available materials, pre-owned cardboard and new combinations of words. Their solution to scarcity was to recycle. At the storefront retreat from business as usual, the two artists began to buy cardboard from practically destitute paper pickers at almost ten times the price paid in recycling centers. Soon the cartoneros themselves came to the workshop to design and decorate cardboard books.

One-of-a-kind covers announce the original material inside: new literature donated by Argentina’s best living writers. Ricardo Piglia and César Aira were among the first, soon followed by Mexican Margot Glantz, Chilean Diamela Eltit and many others. By now, Harvard University’s Widener Library has more than two hundred titles from Eloísa Cartonera, and the University of Wisconsin, Madison, has even more. Several of the former paper pickers in Buenos Aires and in Lima later found work in standard publishing houses; others returned to finish high school. All of them managed to survive the economic crisis with dignity.

Eloísa didn’t set out to be the publishing model for an entire continent and beyond, but her example proved irresistible. Rippling throughout Latin America and before reaching Africa or winning the Prince Claus Award for 2012, the Cartonera project reached Harvard University in March 2007 invited by Cultural Agents for a week of talks and workshops. Javier from Eloísa taught us how to make beautiful books from discarded materials, and Milagros from Sarita showed us how to use them in the classroom.

This was a moment of truth for me and for other teachers of language and literature, crouched on the floor cutting cardboard, and hunched over tables covered in scraps, tempera paints, scissors, string and all kinds of decorative junk. Until then, the Cultural Agents Initiative had been drawn outward, studying impressive top-down and bottom-up art projects that humanistic interpretation had been neglecting. We convened—and continue to convene—conferences, courses, and seminars on thinkers who inspire cultural agents of change, and on a broad range of artists who identify their work as interventions in public life.

But the Cartoneras changed me. I was already primed, having been charmed—and shamed—by two undergraduate maestros at Harvard College. In 2006 Amar Bakshi and Proud Dzambukira had gone to Mussoorie, India, where girls generally drop out of school by age nine. The college students established a non-governmental organization (NGO) that hired local artists to offer after-school workshops for girls who stayed in school. And they stayed. Keeping children in school by brokering art lessons was the kind of cultural agency I could manage.

With this wake-up call I understood that agency doesn’t require genius or depend on particular professions. It can be a part of modest but mindful lives, my own for example. I am a teacher, after all, and the work of education is urgent almost everywhere, including our university-rich area where poor neighborhood public schools face escalating dropout rates and increasing violence. Sarita Cartonera offered an art-making model for linking good literature with high-order literacy, along with admiration for fellow artists. It works at all grade levels, from kindergarten to graduate school.

The principle is simple and the results are astounding: use a challenging text as raw material for creating a new work of art, in any medium. To create your drawing, monologue, dance, song, decorated cookie, explaining the work with reference to a text, you have to read it very well. The practice has become a teacher-training program in literacy and citizenship that we call Pre-Texts. “Make up your mind,” some potential partners demand. “Is it a literacy program? Or is it arts education? Or maybe civic development?” The answer is yes to all, because each dimension depends on the others. Let me explain: (1) Literacy needs the critical and creative agility that art develops; (2) Art-making derives inspirations from critical readings of texts and issues; (3) Finally, citizenship thrives on the capacity to read thoughtfully, creatively, with co-artists whom we learn to admire. (Jürgen Habermas bases “communicative action” on the Aesthetic Education he got from Schiller.) Admiration, many of us have learned from Antanas Mockus, animates civic life by expecting valuable participation from others. Toleration is lame by comparison; it counts on one’s own opinions while waiting for others to stop talking. Pre-Texts is a hothouse for interpersonal admiration, as a single piece of literature yields a variety of interpretations richer than any one response can be. This integrated approach to literacy, art, and civics develops personal faculties and a collective disposition for democratic life.

Literacy should be on everyone’s agenda because it continues to be a reliable indicator for levels of poverty, violence, and disease, and because proficiency is alarmingly low in underserved areas worldwide. Skeptics will question the cause for alarm, alleging that communication increasingly depends on audiovisual stimuli, especially for poor and disenfranchised populations. They’ll even say that teaching classic literature reinforces social asymmetries because disadvantaged people lack the background that privileged classes can muster for reading difficult texts. Audiovisual stimuli on the other hand don’t discriminate between rich and poor and seem more democratic. But public education in the United States is now returning to “complex texts” and to the (literary critical) practice of “close reading” through newly adopted Common Core Standards that value difficulty as grist for cognitive development. Formalist aesthetics would help to make the transition by adding that difficulty is fun; it offers the pleasure of challenges that ignite the imagination.

Paulo Freire cautioned against the pedagogical populism that prefers easier engagements, because full citizenship requires high-order literacy. His advice in Teachers as Cultural Workers was to stress reading and writing in order to kindle the critical thinking that promotes social inclusion. Freire traces a spiral from reading to thinking about what one reads, and then to writing a response to one’s thought, which requires more thinking, in order to read one’s response and achieve yet a deeper level of thought. Teachers democratize society by raising the baseline of literacy, not by shunning literary sophistication along with elite works of art. The classics are valuable cultural capital, and the language skills they require remain foundations for analytical thinking, resourcefulness, and psychosocial development. Paradoxically, skeptics reinforce the inequality they decry by dismissing a responsibility to foster high-level literacy for all.

By now Pre-Texts has partnered with boards of education, schools, and cultural centers in Boston, Colombia, Brazil, Puerto Rico, Mexico, Peru, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Hong Kong, Zimbabwe and Harvard’s Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning. Our current projects include a bilingual program for professors of the Autonomous University of Coahuila, Mexico, along with its network of high school teachers; a growing reach throughout Brazil with O Grupo Positivo; and training for staff and local teachers for the exciting network of 82 new Parques Educativos in Antioquia, Colombia.

Though developed for underserved schools with great needs and poor resources, the approach is a natural for higher education too. Research universities now recognize that art-making can raise the bar for academic achievement, and Pre-Texts makes good on that promise. It has significantly improved my teaching at Harvard, for example. A new undergraduate course called Pre-Textos tackles tough texts by Jorge Luis Borges, Juan Rulfo, Julio Cortázar, Alejo Carpentier and Octavio Paz, though students still struggle with Spanish. The pilot class in 2011 made maps, choreographed, composed music, created storyboards, acted and remarked on the mutual admiration that art-making generated in an intensely competitive campus. For a final project the group decided to coproduce a film based on the short story “Death and the Compass” by Borges. Each member contributed a talent for acting, or directing, or music, costumes, photography, and so forth; and all wrote accounts of their work as co-artist with Borges. For another example, my graduate course Foundational Fictions and Film offers a creative alternative to the standard essay assignment: compose one chapter of your own 19th-century national novel and write a reflection on the process. The new novels and authors’ notes almost always surpass the conventional essays, which hardly anyone elects. Creating a novel demands sensitivity to character construction, to registers of language, historical conflict, social dynamics, and intertextual references. Students will risk this “insider” appreciation of literature if teachers allow it.

Pre-Texts is an intentionally naughty name to signal that even the classics can be material for manipulation. Books are not sacred objects; they are invitations to play. Conventional teaching has favored convergent and predictable answers as the first and sometimes only goal of education. This cautious approach privileges data retrieval or “lower-order thinking.” But a first-things-first philosophy gets stuck in facts and stifles students. Bored early on, they don’t get past vocabulary and grammar lessons to reach understanding and interpretation. Teaching for testing has produced unhappy pressures for everyone. Administrators, teachers, students, and parents have generally surrendered to a perceived requirement to focus on facts. They rarely arrive at interpretive levels that develop mental agility. Divergent and critical “higher-order” thinking has seemed like a luxury for struggling students. However, when they begin from the heights of an artistic challenge, students access lower levels of learning as functions of a creative process. Entering at the base seldom scales up, but turning the order upside down works wonderfully. Attention to detail follows from higher-order manipulations because creative thinkers needs to master the elements at hand.

With Pre-Texts I am finally responding to my own proposal that we offer our best professional work as a social contribution, the way creative writers do when they donate literature to the Cartoneras. Politics isn’t always a pause from one’s field of expertise. For me, literary studies —including theory at the highest level I can muster—is now useful for civic development. This dialogue between scholarship and engagement, thinking and doing, is not a double bind, though the self-canceling figure haunts the humanities like a hangover from heady days of deconstruction.

Literature as recycled material; it had never occurred to me before. The Cartonera book covers made of recycled cardboard became objective correlatives for the recycled material inside. This was my simple summary of Milagros’s practice, cutting through sophisticated literary criticism the way that Javier cut through cardboard. A daunting vocabulary of intertextuality, traces, iteration, permutation, point of view, focalization, influence, and reader-response becomes user-friendly when readers abstract literary functions from their practice of making things with literary prompts. The functions add up to a general principle about literature being made up of reusable pieces, cuts and pastes and pastiches that welcome you to come and play with them.

Winter 2015, Volume XIV, Number 2

Doris Sommer is Ira Jewell Williams Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures and the founder-director of the Cultural Agency Initiative.

Related Articles

Zero Waste in Punta Cana

I never imagined that my job at a leading Dominican resort would be so dirty—at least not at the beginning. I spent my first months as environmental director of…

A Long Way from the Dump

I am the oldest of five children, and from the time I was little I learned to look for toys and food in Guatemala City’s sprawling garbage dump. My grandmother raised pigs, and I had to be in…

Transforming Values

Mounds of garbage amassed on street corners, in front of houses. Bags splayed open, spilling onto the sidewalks, filling the city with stench. For three days…