Reminiscences of the Botanical Garden at Central Soledad

1940-1950

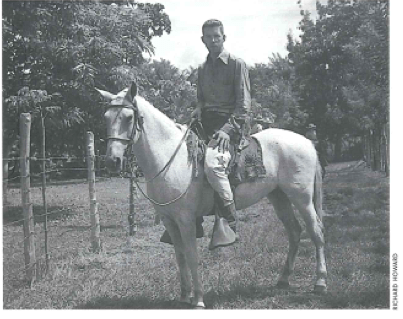

Richard Howard on horseback [1940]

The bus-it was Greyhound, I believe-took us all the way from Boston to Key West that summer in 1940. Then we boarded the ferry to Havana and finally the night train to Cienfuegos in the middle of the Cuban island. If we were not met, aguaguita or local passenger car/bus took us to the botanical garden, our final destination. Back then, graduate students at Harvard were expected to gain some experience in tropical biology by visiting the Cuban garden, known variously as the Harvard Garden in Cuba, the Soledad Garden, and finally the Atkins Institute of the Arnold Arboretum. We had a stipend of $300 for the summer’s room and board and all our transportation expenses.

The botanical collections near the former Central Soledad, in Cuba, developed from the collections of sugar cane clones assembled by Edwin Atkins in 1899. The first superintendent, Robert Grey, was also a plant breeder of sugar cane, and his successor, David Sturrock, expanded the goal of the collection with the addition of fruit trees and timber trees. Sturrock thought the short labor season of the cane harvest could be countered by a market in fresh fruit or the cottage industry of jams and jellies.

Fast-growing timber trees could also supply the needs of local industry for fuel, construction or railroad ties, then met by introduced lumber. Harvard economic botanists Oakes Ames and George Goodale became advisors to Atkins and offered services in the operation and development of the garden. Various Harvard professors visited the garden, avoiding the winter months in Cambridge. Superintendent David Sturrock and his assistant, Frank Walsingham offered instruction or guidance in tropical plants and horticultural practices. The financing and administration of the Garden in Cambridge fell to Elmer D. Merrill, director of the Arnold Arboretum, for botany and Thomas Barbour, director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, for zoology. Merrill arranged for Harvard research appointments to the Garden and to the Arnold Arboretum for Hermano León and other Jesuits residing in Cuba.

Merrill was good to students too. Organized classes in Harvard Summer School were developed after World War II, and Merrill arranged for travel from Cuba to Honduras on the “Great White Fleet,” courtesy of the United Fruit Company.

Harvard House served as headquarters for visitors to the garden. A small library was maintained along with an herbarium in three standard cases. A spacious laboratory permitted processing of collections as well as some microscope work or chemical procedures. A small darkroom was in an attached building. Two large bedrooms occupied the interior of the building, an office and dining area continued the floor plan. A central screened porch with rocking-chairs held the nightly pre-dinner gathering for a “Sturrock’s special” – a rum punch. A separate building to the rear was the kitchen and living quarters for Teodoro, the Spanish cook, and Manuelo, the Cuban houseboy. The Sturrocks lived in the newly constructed Casa Catalina on the ridge overlooking the Garden.

I visited the garden as a student in 1940 and 1941, again in 1944 while I was in the U.S. Air Force, and in 1950 and 1951 as the instructor in a Harvard course in tropical botany. On most visits I collected botanical specimens, including 38 sets of Plantae Exsiccatae Grayanae which became highly prized distributions of the Gray Herbarium. I also prepared a students’ manual to the flora of the areas commonly visited by collectors and classes. Brother León learned of my manuscript and objected to its publication. It seems that Nathaniel Lord Britton, director of the New York Botanical Garden and long-term scholar of the Antilles, had prepared a Flora of Cuba guide before his death, and Brother León was committed to translate the book into Spanish for simultaneous publication in the two languages. Years later, I found Britton’s unpublished manuscript in the New York Botanical Garden archives. The Spanish version was published in parts by León (1948), León & Alain (1951, 1953, 1957) and Alain (1962).

John George Jack of the Arnold Arboretum staff collected botanical specimens in Cuba between 1926 and 1936. Jack’s collecting localities were given in English as Copper Mine, Glen Ames, Belmonte and Mt. Harvard. These names or localities were not known to Cubans then or now. Finding Jack’s localities was a particular goal of mine. Travel around the Garden was on foot or, rarely, in a Model T Ford which belonged to Dr. Barbour. I had the requisite long legs needed to occupy the seat placed to accommodate Barbour’s stately girth. Horses were used for travel into the Trinidad-San Blas mountain areas. Priscilla, Dr. Jack’s horse, had been trained to push into the brush and/or remain still while Jack stood in the saddle to collect specimens. Priscilla, and I spent many hours collecting plants. In post-World War II years a surplus jeep was available for collecting on serpentine soils or following rough coastal trails. Horses available for classes were used in the winter cane harvest and then turned to pasture. These animals commonly objected to a summertime roundup and transport of visiting students.

Rochard Howard at the tree planting ceremony in November, 1999.

Following the Cuban revolution, complicated labor rules and fiscal regulation caused Harvard to withdraw from the Cuban Garden. Cuban authorities assumed direction of the garden, which was renamed JardÃn Botanico de Cienfuegos. The sugar mill was renamed Central Pepita Tey.

With the travel restrictions imposed as part of an embargo against Cuba, Harvard students no longer had access to the Garden. The development of the research area, gardens and programs in Costa Rica as the cooperative Organization for Tropical Studies, of which

Harvard is a member, perhaps serves as a partial or inadequate alternative to the Cuban operation. The Soledad years were formative to my career, and I acknowledge my gratitude for all I derived from that experience.

Winter 2000

Richard A. Howard is director of the Arnold Arboretum and professor of dendrology emeritus. He recently traveled to the Cienfuegos Botanical Garden to participate in a two-day conference (see accompanying story); the Cuban delegation honored him by planting two new palm trees.

Related Articles

Isabelle DeSisto: Student Perspective

encountered the first obstacle of my trip to the Isla de la Juventud before I even left Havana. Since American credit cards don’t work in Cuba, I couldn’t buy my plane tickets online. But that…

Honoring Humanity: An “Interview” with Richard Mora

Mauricio Barragán Barajas: Why don’t we begin by having you introduce yourself? RM: Alright. I was born in East Los Angeles, and grew up in Cypress Park, a barrio in…

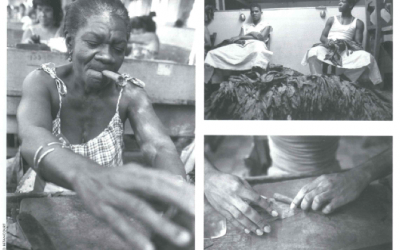

Tobacco and Sugar

“Tobacco and Sugar” is the course that focuses American literatures on the Caribbean, and that acknowledges the unavoidable importance of monocultures for cultural studies. Much of the…