Researching Mayan Languages

One Fieldworker’s Experiences

I was walking back to my hostel in San Cristóbal Verapaz, Guatemala. Following a morning of classes in the Poqomchi’ Mayan language, I automatically greeted the indigenous hostel owner (dueña) in Poqom— K’aleen, tuut. Suq na ak’ux?—literally, “Hello, ma’am. Is your chest well?”— the Poqomchi’ way of asking “How are you?” Just as she began to reply, her twenty-year-old daughter burst into the room to ask a question in fluent Spanish. The dueña’s immediate, chastising response was: “Adam’s been here for a week and he’s already speaking Poqom. We should speak in Poqom, too!”

I’d waited to hear these words since the summer of 2007, a full year before I began my research in Guatemala. The country’s twenty-two Mayan languages make it a linguist’s paradise. Some, such as K’ichee’ or Q’eqchi’, have hundreds of thousands of speakers and enough social standing to ensure their prominence for several more generations. Less fortunate tongues, like Itzá, will disappear when their few remaining speakers, all elderly, pass away. Poqomchi’ and Tz’utujil, the two languages which I researched, lie somewhere between these extremes. With tens of thousands of speakers each, they are assured of immediate survival but not of long-term vitality.

Mayan languages here owe their uncertain futures to Guatemala’s brutal history. In the 16th century, conquistadors subjugated indigenous polities and imposed Spanish as a new, elite lingua franca. During the country’s Civil War (1960 – 1996), the military and paramilitary forces wiped out whole indigenous towns and ethnolinguistic communities, using the threat of leftist insurgents as a pretext to target ethnic Maya.

Reversing the age-old “Spanish Only” language policy, the 1996 Peace Accords acknowledged that Guatemala is a multilingual nation. Today, the official government-supported Academia de Lenguas Mayas is busy producing high-quality grammars, dictionaries, and text collections, and it runs regional offices in each Mayan ethnolinguistic community. Despite this progress, however, the replacement of indigenous languages by Spanish continues to sever indigenous communities’ ties with their own past. The mentality that Spanish is somehow “superior” to Mayan languages remains common. How can the rich cultural heritage passed down via these languages endure if so much of Guatemalan society thinks them worthless?

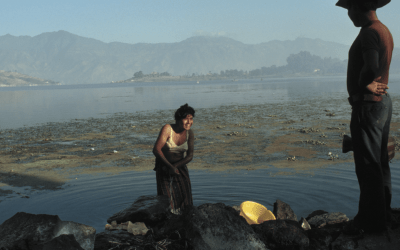

Change in communities’ attitudes must come, first and foremost, from the communities themselves. But my fieldwork experiences taught me that a well-intentioned outsider can encourage positive attitudes toward local languages. In the hillsides surrounding the town of Uspantán, Department of El Quiché, elderly locals expressed astonishment that a non-Maya would ever greet them in K’ichee’. In response to my cheery greeting of K’aleen, jaw! (“Hello, sir!”), a fruit vendor in San Cristóbal Verapaz started to teach his Spanish-speaking grandson to address passersby in Poqomchi’. And in San Pedro la Laguna, the Tz’utujil town where I lived and conducted the bulk of my research, a group of young men reacted with enthusiasm and amusement when I stopped to say Qaq’iij, “good afternoon.” Used to the many tourists who come for the great views of Lake Atitlán and the cheap marijuana, these Sampedranos had probably never known any outsider who considered Tz’utujil more than, as it is pejoratively called on the street, mere “dialecto.” One woman asked me, with evident pleasure on her face, how I had come to find an interest in “nuestra lengua.”

I wouldn’t dare to suggest that my three research trips have in any significant way changed the prospects for the Mayan languages. But speaking with Maya people atop the Uspantán hills, on the street in San Cristóbal, and next to Lake Atitlán in San Pedro, I saw how the genuine interest of a field linguist can help reinforce the notion that all languages have worth.

Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1

Adam Singerman ’09 is currently the Prep Program Fellow at the Instituto de Liderança do Rio (Rio Leadership Institute), based in Rio de Janeiro. At Harvard, he designed a special concentration in “Linguistics & Latin America.” He spent the summers of 2007 and 2008 and Christmas 2008 in Guatemala with funding generously provided by DRCLAS, the Office of International Programs, the Harvard College Research Program, and the Committee on Special Concentrations. Contact: adamsingerman@gmail.com

Related Articles

Guatemala: Editor’s Letter

The diminutive indigenous woman in her bright embroidered blouse waited proudly for her grandson to receive his engineering degree. His mother, also dressed in a traditional flowery blouse—a huipil, took photos with a top-of-the-line digital camera.

Making of the Modern: An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann

Making of the Modern An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1Related Articles

Increasing the Visibility of Guatemalan Immigrants

Guatemalans have been migrating to the United States in large numbers since the late 1970s, but were not highly visible to the U.S. public as Guatemalans. That changed on May 12, 2008, when agents of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) launched the largest single-site workplace raid against undocumented immigrant workers up to that time. As helicopters circled overhead, ICE agents rounded up and arrested …