Resistance to Mining in El Salvador

A Battle for Water, Life, and National Sovereignty

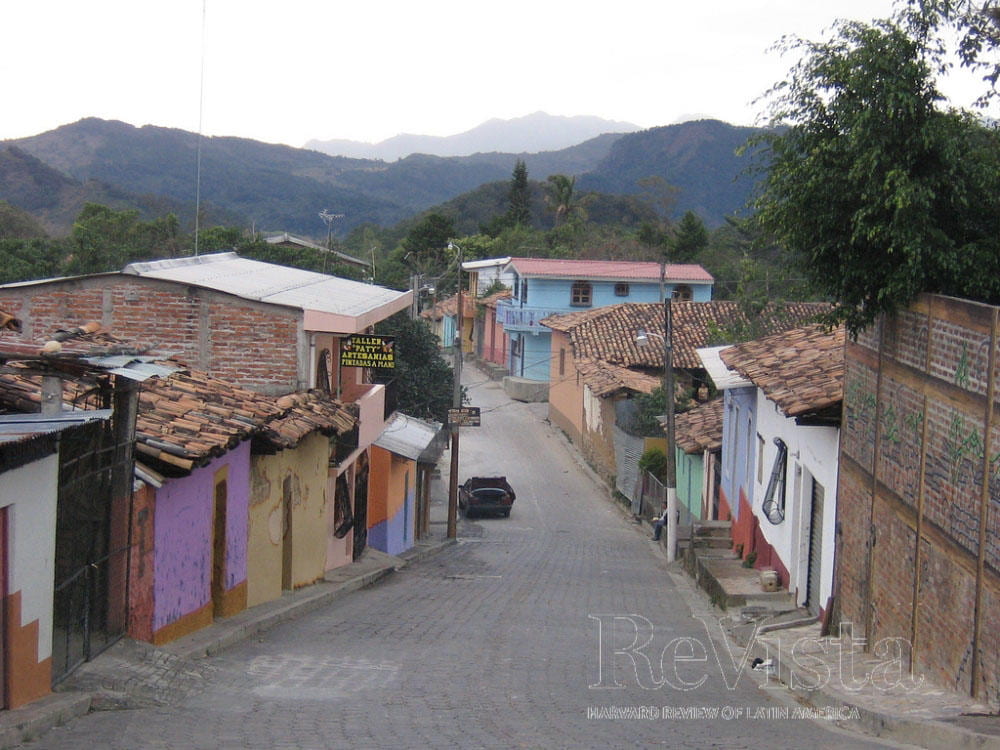

El Salvador’s small towns were rocked by the bloody and protracted civil war (1980-1992). Now, mining is causing social conflict and violence in many of the same communities. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Will tiny El Salvador, where half the rural population lives on less than two dollars a day, become the first nation on the planet to legally ban gold mining? Or will profit-maximizing transnational mining companies succeed in using investor-friendly international trade tribunals to trump national sovereignty and popular demands for water security, environmental protection, and sustainable development?

This epic conflict is playing out today on an unlikely battlefield, a country still struggling to bolster its fragile democratic institutions some twenty years after a brutal civil war. It illustrates the challenges faced by a developing country that is seeking to determine an environmentally and socially responsible mining policy, when foreign investors’ rights loom large over domestic policy decisions.

ORIGINS OF THE CONFLICT

The controversy over mining in El Salvador has focused on Pacific Rim, a Vancouver-based transnational that acquired a permit in 2002 to begin exploratory activities for a massive gold mine in Cabañas, located in the Lempa River basin. The Lempa, El Salvador’s largest river, is one of the few remaining uncontaminated water sources in the country. Its watershed extends to nearly half the national territory, including the capital city of San Salvador. More than three million Salvadorans rely on this water each day for drinking, farming, fishing, livestock rearing, and hydroelectric power.

Never a strong feature of the national economy, mining was effectively halted in El Salvador by the civil war (1980-1992). But Pacific Rim’s initiative signaled the start of a twenty-first century mining boom. Lured by rising global commodity prices and lucrative investment opportunities under the Dominican Republic–Central American Free Trade Agreement (DR-CAFTA), transnational companies had filed 29 exploratory permits for gold mining in El Salvador by 2008.

At the same time, mounting concerns by local communities about the potential environmental and social risks of Pacific Rim’s project were widening into a broad national resistance movement against metallic (gold and silver) mining. In 2007, the Catholic Church of El Salvador issued a formal proclamation against mining signed by seven bishops and one archbishop. Later that year, a national poll revealed that more than six out of every ten Salvadorans were opposed to metallic mining. The National Roundtable Against Metallic Mining (known as the Mesa), a coalition of community, environmental, and other civil society organizations formed in 2005, mobilized this growing anti-mining sentiment into an effective political force and pressured the government to review El Salvador’s mining policy.

In March 2008, conservative President Tony Saca announced a temporary ban on metallic mining permits in El Salvador, pending further study and reform of the mining law. As a result, Pacific Rim abandoned the feasibility study it had begun in order to obtain an exploitation permit for its mine, the next stage in the process required to actually begin operations. In July, the company ceased exploratory drilling and effectively halted all mining preparations.

THE CASE AGAINST MINING

The case against Pacific Rim, and metallic mining generally in El Salvador, has been effectively articulated by the Mesa. Large-scale gold mining operations, the Mesa argues—especially the water-intensive cyanide ore process used by companies like Pacific Rim—pose a significant threat to rural economies and local drinking water supplies. The average metallic mine uses 24,000 gallons of water per hour, or about what a typical Salvadoran family consumes in 20 years. Toxic runoff, spreading to the surrounding land, can contaminate rivers, creeks, and ground waters. The Cabañas region is also prone to earthquakes and torrential rains, further heightening public health and safety concerns.

A case in point is the San Sebastián mine operated by the Milwaukee-based Commerce Group in the department of La Unión, whose exploitation license was revoked by the government in 2006 on environmental grounds. Decades of gold extraction at the site have turned the waters of the river a rusty red color, a classic sign of “acid mine drainage.” Recent government tests have found nine times the acceptable level of cyanide and one thousand times the acceptable level of iron in the water, while public health studies confirm an unusually high incidence of kidney failure, cancer, and skin and nervous system disorders in the local population.

While the jobs promised by Pacific Rim and other mining companies may seem tempting to poor communities, the Mesapoints out that few local residents have the technical skills to qualify for them. And while the lure of increased tax revenues is perpetually attractive to an impoverished government, under existing law, only three percent of mining profits would be captured by the public sector. In any case, the projected operational life of Pacific Rim’s Cabañas mine is just six years.

Mining has also caused social conflict and violence in communities still struggling to overcome the effects of the protracted civil war. According to the Mesa, Pacific Rim targets funds for scholarships, schools, and other benefits to municipalities (and mayors) not directly impacted by mining, creating friction with those communities that are affected. As one local activist has lamented, “Now in our communities, you don’t trust people you’ve trusted your entire lives.”

Four anti-mining activists in Cabañas have been killed since 2009 in what the Mesa describes as targeted assassinations. Dozens more, including environmental leaders, priests, and community radio journalists, have received death threats, which the company blames on “internal feuds”—the very conflicts that its presence has created. While some of the perpetrators of these murders have been convicted, the “intellectual authors” of the crimes have never been prosecuted. For anti-mining activists, the persistence of this climate of impunity evokes bitter memories of the civil war, with communities once again facing the threat of displacement and loss of land and natural resources that their members fought and died to protect.

The government’s de facto moratorium on new mining permits has remained in effect, extended by leftist FMLN President Mauricio Funes for the duration of his administration (through mid-2014). Funes is now seeking to formalize the moratorium through a law that would suspend metallic mining until El Salvador develops the necessary institutional structures to better control its social and environmental impacts.

The Mesa is pushing the government to go one step further, by legislating a permanent ban on metals mining. El Salvador, they note, is a world leader in water scarcity, climate risk, and environmental degradation, with 96 percent of its surface water already contaminated and only three percent of its original forest cover left intact. Under these conditions, they argue, a mining industry can never be environmentally sustainable. “We can live without gold,” says the Mesa, “but not without water.”

GLOBALIZING THE CONFLICT

Still, with the powerful new global weapons available to Pacific Rim and other mining transnationals, even a permanent legislative ban may not be enough. In December 2008, Pacific Rim inaugurated a new stage in the country’s mining wars by bringing the first legal challenge to a sovereign government’s environmental policy under DR-CAFTA. Arguing that the government’s failure to approve an extraction permit violated investors’ rights under the international trade agreement, Pacific Rim sued El Salvador for $77 million in damages in the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), a World Bank court.

Despite Pacific Rim’s best efforts to transfer ownership of the mine to a newly incorporated Nevada subsidiary, ICSID ruled that Pacific Rim, a Canadian firm, could not proceed under DR-CAFTA (to which Canada is not a party). However, it allowed the case to go forward under El Salvador’s own 1999 investment law, which has permitted foreign companies to remove such “investor-state” claims to international tribunals. Subsequently, Pacific Rim upped its damage claim to $315 million—an amount roughly equal to two percent of El Salvador’s GDP, and half of its education budget. The merits of the case have yet to be adjudicated.

A similar case brought by the Commerce Group against the Salvadoran government at ICSID was dismissed on a technicality. Still, the government was forced to pay $800,000 to ICSID in legal fees. To date, the government has spent at least $5 million on mining litigation costs—an enormous sum for an impoverished country.

As the Mesa and its allies charged in a recent open letter to the World Bank, “Pacific Rim is using ICSID and the ‘investor-state’ rules of a free trade agreement to subvert a democratic nationwide debate over mining and sustainability in El Salvador.” And the strategy has been gaining traction with other transnationals, especially those involved in natural resource conflicts in Latin America. According to a recent report by the Institute for Policy Studies, of the 169 cases currently pending at ICSID, 60 (36 percent) involve mining or hydrocarbons extraction—up from 3 a decade ago. More than half of these disputes are in Latin America.

Recognizing that the causes of, and solutions to, El Salvador’s mining problems lie well beyond its borders, the Mesa has increasingly adopted a transnational perspective. It has joined forces with anti-mining activists in Honduras and Guatemala to resist extractive projects there that could poison El Salvador’s rivers before they even reach its borders. Some 49 proposed metal mining projects in these neighboring countries represent a significant threat of transborder contamination to El Salvador.

The Mesa is also working with a broad-based hemispheric alliance of fair trade, human rights, environmental, and religious groups in the United States and Canada to pressure Pacific Rim to withdraw its case from the international courts. They cite the precedent of Bechtel, a U.S.-based conglomerate that was forced to settle its $25 million claim against the Bolivian government (for cancelling its water privatization contract) for a token payment. The coalition is also seeking to eliminate unfair “investor-state” clauses from trade and investment treaties, while helping to extricate El Salvador and other countries from agreements that allow foreign investors to hijack local democracy.

The Mesa and its allies have recently celebrated some noteworthy (albeit limited) victories. Canada-based Goldcorp, the second largest mining company in the world, has temporarily suspended operation of its gold mine in Guatemala near the headwaters of the Lempa River, citing unfavorable economic conditions. An ICSID tribunal has dismissed the Commerce Group’s appeal of the court’s earlier decision denying jurisdiction, after the Commerce Group failed to post the required deposit. And the Salvadoran Congress has amended its investment law to require “investor-state” disputes to be adjudicated in the domestic courts, unless they are covered by a treaty that explicitly allows removal to an international tribunal.

Still, in the run-up to the tightly contested 2014 presidential election, the legislative proposals to ban mining—either permanently or conditionally—appear to be stalemated in political gridlock. While it may be easier for El Salvador to renounce mining than for countries already heavily dependent on mining revenues—including those with leftist governments like Bolivia and Ecuador—potential liabilities under trade and investment laws also affect the political calculus. Whether the costly and protracted “investor-state” legal challenges confronting El Salvador will have a sufficiently chilling political effect to discourage an environmentally and socially responsible mining policy remains to be seen.

Emily Achtenberg is an urban planner and an independent researcher on Latin American social movements and progressive governments. She has covered the mining conflict in El Salvador in her biweekly blog for NACLA (nacla.org/blog/rebel-currents).

Related Articles

Urban Mining

Consider two seemingly unrelated issues: rising urban poverty and electronic waste. The Cities Alliance estimates that urban slums in developing countries are growing by…

First Take: Two Tales of Mining and Human Choice

Two tales of very small human settlements with mining potential may help us reflect on what Latin America, on a larger scale, faces today regarding the exploitation of minerals from its territories. At these two settlements, mining was stopped because of human choices and…

Power, Violence and Mining in Guatemala

It was another cold summer’s night in the Guatemalan highlands when I received a devastating phone call.“Yoli has been shot!” said a voice on the other end. Frantically, I gathered all the information I could: Was she alive? Where is…