RFK Professor Roberto Schwarz

The “Misplaced” Intellectual

Roberto Schwarz Folha UOL)

Roberto Schwarz, Robert F. Kennedy Visiting Professor this past semester, is one of the foremost Latin American intellectuals whose critical work spans 25 years. Students who took his Romance Languages & Literatures graduate seminar on 19th century writer Machado de Assis, a preeminent Brazilian novelist, found the setting challenging but comfortable, and they described Schwarz as “extremely knowledgeable, intellectually honest and accessible.”

Schwarz was born to a leftist Jewish family who remained in Austria “longer than it should have” – Germany annexed Austria in March 1938, forcing Professor Schwarz’s family left to flee in August. Many factors made Brazil the destination point of this Austrian family, the decisive one being the fact that most other countries had quotas or placed other obstacles in the way of Jewish families. This exile would have an impact on Schwarz’s relation to Austrian culture. He says he considers himself an Austrian of the 20s and 30s, despite having been born in Vienna in 1938, pointing out “the only contact I had with Austrian culture (German was spoken at home) was through my parents, who belonged to that generation.”

In 1969 he would face exile once again, although this time it would not be permanent. A 1964 military coup began to have repercussions in the intellectual life of the country in 1968. Prior to that period, the university itself had been able to co-exist with military rule, according to Schwarz, who observed “despite the existence of a right-wing dictatorship, the cultural hegemony of the left [was] virtually complete” (Culture and Politics in Brazil: 1964-1969). As long as they did not organize meetings with workers, farm laborers or seamen, the Castelo Branco government made no attempt to persecute socialist intellectuals or prevent the circulation of their artistic (or even doctrinal) material. However, after students emerged as a powerful group desiring to re-establish links between cultural production and the masses, the regime responded with repression in December 1968. After this so-called “coup within the coup,” many intellectuals were formed to emigrate.

Schwarz went to Paris in 1969, where he taught Brazilian literature and continued his graduate studies. He had pursued studies in literature before (1961-1963), obtaining a masters degree from the Department of Comparative Literature at Yale University, which was then directed by the famous comparatist René Wellek. His prior training had been in the social sciences (University of São Paulo, 1957-60) -training that influenced what later became his materialist approach to literature. With a French government scholarship, he completed his studies in literature at the Sorbonne with a dissertation on Machado de Assis.

Schwarz reflects on exile as an idea, as well as an experience, noting that the intellectual in exile often has to face a cruel paradox. “While the socio-political [and thus collective] circumstances that lead a person to leave a country might be terrible in themselves, being exiled can sometimes be productive at an individual level,” he observed. “In terms of my intellectual experience, the years in Paris were extremely productive. In Paris, for example, we could discuss Brazil’s situation, something which could not have happened in Brazil after 68. The Brazilian community there was very active. My friendships with many people date back to those years. Actually, since the community was composed of people from so many different Brazilian states, being together in Paris gave us a sense of unity. It was, in a way, the space in which I started to develop my own sense of being a Latin American intellectual.”

Upon his return to Brazil in 1978, Professor Schwarz became a Professor of Literary Theory at the University of Campinas, São Paulo. His preference for a materialist interpretation of cultural history –“an attempt to approach aesthetics from a leftist point of view”– has resulted in many sophisticated works of critical theory. His books include A Sereia e o Desconfiado, Ao Vencedor as Batatas: Forma Literaria e Proceso Social Nos Inicios do Romance (1977), O Pai de FamÃ’ia (1978), Que Horas São? (1987), Um Mestre Na Periferia do Capitalismo: Machado de Assis (1990) andMisplaced Ideas: Essays on Brazilian Culture (1992).

Schwarz concerned himself in his studies of Machado de Asis with the narrative consequences of the persistent gap in Brazilian society between liberal ideology (based on free market) and its local “degradation” by the reality of forced labor (slavery). However, the central point is not that incompatibility in itself. According to Schwarz the crucial element was patronage or favor (clientismo), the socio-economic relationship between landowners of the latifundiums and theagregados. Although considered free, agregados were actually dependent, neither proprietors, nor proletarians; people whose access to social life and its benefits depended on the favor of a wealthy and powerful family. Whereas slavery blatantly contradicts liberal ideas and fixes social roles, patronage uses them for its own purposes. Both proprietor and agregadoidentify through their not being slaves. Through this identification, they re-assert a stiffled social relation, while giving the appearance of social mobility. In these circumstances, both slavery and liberalism receive a relative sort of validation.

This situation has a curious repercussion in Machado’s novels, which often exhibit a dialectic relationship between content and form. For example, Schwarz explores the relationship between some of his narrators capricious narrative scheme and the contradictory desire of the 19th century slave-owning society to enter the modern world, while incongruously keeping in place a social system that could be seen incompatible with modernization. Schwarz observes that Brazil often gives an impression of “ill asortedness,” what he defines elsewhere as “unmanageable contrasts, disproportions, nonsense, anachronisms and outrageous compromises.” This “ill assotedness”- elegantly displayed in Machado’s texts-partially corresponds (though not ideologically) to the combinations which the art of Brazilian Modernism, and later on, Tropicalism, have taught us to appreciate. Schwarz is now tracing some of the topics already examined in Machado’s novels in the work of other Brazilian authors. He believes that those issues have not died out, but rather they have changed in what he calls Brazil’s heterodox modernization.

Winter 2000

Carmen Oquendo-Villar is a Ph.D. candidate in Harvard’s Department of Romance Languages and Literatures working in Latin American literature in Spanish and Portuguese.

Related Articles

Isabelle DeSisto: Student Perspective

encountered the first obstacle of my trip to the Isla de la Juventud before I even left Havana. Since American credit cards don’t work in Cuba, I couldn’t buy my plane tickets online. But that…

Honoring Humanity: An “Interview” with Richard Mora

Mauricio Barragán Barajas: Why don’t we begin by having you introduce yourself? RM: Alright. I was born in East Los Angeles, and grew up in Cypress Park, a barrio in…

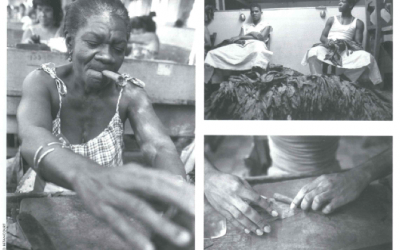

Tobacco and Sugar

“Tobacco and Sugar” is the course that focuses American literatures on the Caribbean, and that acknowledges the unavoidable importance of monocultures for cultural studies. Much of the…