Rio de Janeiro’s Favela Tourism

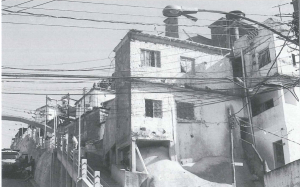

A view of a favela. Photo by Ben Penglase.

I first stumbled upon the existence of favela tourism in the glitzy lobby of a Copacabana hotel. Amongst flyers at the reception desk announcing visits to the city’s famous sights, such as the Pão de Açúcar and the Corcovado, I found a pile of leaflets entitled “Favela Tour.” Curious, I picked one up. It seemed strange to find amongst such mainstream trips an ad for visits to favelas, the shantytowns which cover many of Rio’s steep hills and are linked to poverty, violence and drug trafficking in the minds of many. The flyer featured a photograph of a group of middle-aged tourists against a backdrop of small brick houses perched along a steep incline. The tourists, contented and secure, gazed at the scene with their cameras in hand. My first reaction was of discomfort. I couldn’t imagine visiting a community living in poverty, and then returning to my hotel room to place a check mark on one more of the city’s must sees. Favelas would need to remain poor and officially dangerous for tourists in order to be worth visiting, and there was something voyeuristic and exploitative about visiting a shantytown while expecting it to remain “just so” despite the continuous gaze of tourists.

Indeed, as Harvard graduate student Ben Penglase points out, “These communities have been romanticized and denigrated in many different ways. It’s a complicated subject.” Adds Penglase, who is writing his doctoral dissertation on local politics in a favela, “It’s almost never the people who live in the community who have any control over how they are represented.”

Oddly, the flyer seemed to anticipate this reaction. The description of the tour focused on community organization and claimed to change the reputation of favelas, “often related to violence and poverty only.” Underneath the photograph, I was amused to read: “Informative and surprising, not voyeuristic at all.” It was ridiculous, I felt, to deny voyeurism while presenting a picture of tourists photographing a community from afar. But the more I thought about it, the more this contradiction seemed the perfect way to package favelas for tourist consumption. It tempted our curiosity by evoking the recognizable stereotype of urban poverty, which it also promised to undermine. And it implied that our presence would be welcome where it most likely was not.

This marketing strategy has worked, and favela tours have become an important part of Rio’s tourism. It’s certainly not the first attempt to market this type of tourism to the “other.” One has to go no further than the New York City tours to Harlem or the old Bowery. In Rio, two large tour companies dominate the market, although many independent guides also offer their services. The company “Favela Tour,” whose flyer first attracted my attention, has been in operation for almost 10 years, and now takes close to 4500 clients a year to visits to Rocinha (one of Rio’s largest favelas) and Vila Canoas (a much smaller community). Company owner Marcelo Armstrong says the international clientele is 65% from Europe and 20% from the United States. His clients come from all social and economic backgrounds, from young backpackers to older clients staying in five star hotels. The rival company, “Jeep Tours” also takes visitors to Rocinha in, as the name indicates, convertible jeeps, ideal for rough terrain.

As a genre, favela tours tend to be grouped with adventure tourism rather than cultural sightseeing, as if poverty and semi-legal conditions render favelas closer to nature than other urban destinations. Some tourist guidebooks take up this city vs. nature dichotomy by describing favelas as independent and close-knit entities divorced from their urban surroundings. The Insight Guide describes a favela as “an anthill, bustling with activity.” The Rough Guide talks about the difficulties of favela life, as well as their picturesqueness: “Clinging to the sides of Rio’s hills and glistening in the sun, they can from a distance appear not unlike a Medieval Spanish hamlet, perched secure atop a mountain.”

Favelas are perfect urban candidates for “off the beaten track” adventure tourism because they are marked off from the rest of the city by geography. Rio’s south zone thoroughfares were designed on flat areas in a systematic grid, while favelas are restricted to the steep slopes of the hills, or “morros,” scattered within the city. Favelas are also literally off the map. The hills separating different neighborhoods are colored in green in most tourist maps, giving no recognition to the unofficial constructions covering them. Yet whenever I walked along the shady streets of Copacabana, I could rarely look up without catching a glimpse of reddish brown houses looking down from between the neighborhood’s tall gray apartment buildings. Always in sight, favelas are constant reminders that maps do not tell all, and that Rio’s dramatic hills belie social inequalities which are just as drastic.

I finally opted to go visit a favela. I simply could not decide whether such tours were constructive cultural experiences or simply a means to exploit the myth of an urban “noble savage,” without experiencing them myself. On a warm and cloudy afternoon, I set out with fellow students from my summer language program towards Leme, a small neighborhood at the far end of Copacabana. We met Mido, an independent guide, at a boardwalk restaurant, and headed away from the beach for a mere three blocks before starting the steep walk up to the small community of Chapéu Mangueira. The road soon narrowed so that we had to walk almost single file. The muddy pathways had no name and swerved around in a haphazard manner. They were lined with modest constructions sometimes two or three stories high. Some buildings were simple, made of bare bricks with tin roofs, while others bordered on the coquettish, with bougainvilleas crawling through front gates into the street. At one corner, I glanced away from the slippery path and found myself gazing at the sea from the same height as the top floor of a nearby Leme apartment building. We first stopped at a health center and at a kindergarten, and Mido explained that both were built and maintained with community resources. The small center primarily served to provide information on issues such as sexuality and nutrition, although it was also equipped to provide basic care. The kindergarten doubled as a day care center, so that working mothers could leave their children during the daytime. In both places, community residents kindly greeted us. People seemed accustomed to answering all types of questions, and did not appear to mind our faltering Portuguese.

Next, we halted at a small convenience store and sat on benches where we could chat and look out onto the narrow alley. Only a few people were walking around the neighborhood. Mido explained that many residents worked down in Rio, making this favela quiet during the day. Quite a few people preferred to use the term “comunidade,” disliking the social stigma associated with living in a favela. Most of this favela’s inhabitants were Afro-Brazilians from the state of Minas Gerais, and the community grew through family connections, we learned. New arrivals would stay with relatives for some time, and then move on to build their own house on some clear land. The favela grew from the bottom up. The best established residences were lower down, while the newest and poorest houses were higher up, making up for lack of infrastructure with an even better view.

Despite being labeled a favela, this community was not as poor as I had expected. Most houses looked solid and weatherproof, with running water and electricity. Many even sported a satellite dish on their roof. Plump dogs wandered around the pathways, and my Guaraní soda cost one real, as it would at any beachfront Copacabana kiosk. I was surprised to discover that the term favela, which today synonymous with shantytown, originally designated a tree which grew high on Rio’s hills. Newcomers claimed to where the favelas were, and these communities of squatters slowly assumed the name. As we left Chapéu Mangueira, descending a steep staircase neatly hidden between two apartment buildings, I did not regret my trip. In many ways, I was presented with a sanitized version of favela life, but it wasn’t packaged in the exotic terms that I had anticipated. I discovered that not all favelas are synonymous with poverty, and that the presence of visitors could bring some money into their economy.

Our guide was a Chapéu Mangeira resident who contributes part of his earnings to community maintenance, and Marcelo Armstrong’s company helps support a handicraft center where residents can sell their wares. One question kept troubling me. Why did favela tourism become popular in Rio, and not anywhere else? I could not imagine tours visiting “paracaidistas,” or parachuters, as squatters are commonly known in Mexico City, although many live in similar conditions. But “paracaidistas” do not have the breathtaking view of many favelas, I decided, nor are they often romanticized in popular culture. Rio’s famous “escolas de Samba,” which liven up the city’s carnival, are often based in favelas and contribute to their mystique by linking them with exuberant and reckless festivities. The touristy “Feria Hippie,” held every Sunday in Ipanema, has a corner devoted to naïve paintings of Rio’s favelas: tiny square houses covering a steep hill like an irregular mosaic, framed by a bright blue sky and an occasional palm tree. The exotic image of favelas has also spread beyond Brazil. In 1996, Michael Jackson’s music video “They don’t care about us,” was filmed in Rio’s Santa Marta favela. And in Paris, the restaurant and nightclub “Favela Chic” provides the city with a steady flow of Brazilian music.

Despite the importance of realizing that Rio is not all glamour, what first catches the eye of many potential favela visitors is the romance and danger associated with the concept. The curious fascination provoked by favelas reminded me of Edward Said’s argument in Orientalism, where the western gaze, though mesmerized by the Orient’s mystique, also functioned as an instrument of cultural and imperialist control. Like the Orient for the West, favelas are defined as an exotic “other” for the tourist, whose gaze also has the power to define the ways in which favelas can relate to outside communities. Today, favelas still need to fit into the category of “no man’s land” to draw attention in the public domain, as Radio Favela, an organization based in Belo Horizonte, well knows. Its web page welcomes visitors with a sign that reads “entre aquí, se for capaz,” enter if you dare.

Winter 2002, Volume I, Number 2

Viviane Mahieux is a graduate student in Harvard’s Department Romance Languages and Literatures and is working on urban chronicles in early 20th century Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. She went to Rio on a Foreign Language and Area Studies (FLAS) grant of the U.S. Department of Education to study Portuguese.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Tourism

Ellen Schneider’s description of Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega in her provocative article on Nicaraguan democracy sent me scurrying to my oversized scrapbooks of newspaper articles. I wanted to show her that rather than being perceived as a caudillo

Recreating Chican@ Enclaves

Centrally located between southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, is a hundred-mile long by seventy-mile wide intermountain basin known as the San Luis Valley. Surrounded on the east …

Tourist Photography’s Fictional Conquest

Recently, while walking across the Harvard campus, I was stopped by two tourists with a camera. They asked me if I would take a picture of them beside the words “HARVARD LAW SCHOOL,” …