Roots of Violence in Colombia

Armed Actors and Beyond

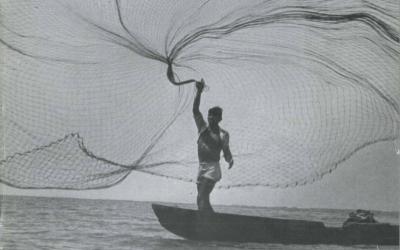

Underage paramilitary boys. Photo by Stephen Ferry.

Colombia has suffered from high levels of armed strife for most of its history. The current strife it is experiencing is not unusual either in length or death toll.

In the 19th century, killing people required more effort because primitive weapons often misfired or missed altogether. Nonetheless, between the 1820s and 1879, an estimated 35,000 Colombians (out of a million or so inhabitants) lost their lives in civil warfare. As a proportion of the population, this is roughly the equivalent of a US death toll of five to ten million between 1950 and 2000. Or about half a million Colombians in the same half century—not far from the rate of the actual numbers.

Colombian violence has reached at least a dozen peaks of intensity since the 1820s. The 20th century dawned over a paroxysm of partisan strife known to history as the War of a Thousand Days. Subsequently, from 1948 to 1964, some 80,000 to 200,000 died in murderous partisan warfare that came to be called “La Violencia.” More than 50,000 died in the Drug Wars of the 1980s and in the escalating guerrilla warfare of the 1990s.

Death tolls this high for such a long time are unusual, even in the 20th century. As many as a million people may have died in the Mexican Revolution, but more perished from disease and dislocation than combat. In more recent times, the last paroxysms of the cold war imposed a heavy toll on Latin America—30,000 died in Argentina between 1976 and 1982, perhaps 300,000 in the Central American wars between 1978 and the early 1990s. Other examples could be cited, but it is difficult to escape the conclusion that Colombia’s history is one of the most violent in the hemisphere, with organized killing existing at chronically high levels, punctuated with episodes of high intensity murderousness, for nearly two centuries.

Why has Colombia suffered from high levels of endemic violence for such a long time? What conditions have tended to cause already high homicide rates to escalate into intense periods of mass murder?

Historians of Colombia usually cite two sets of causes for the routinely high rates of homicide Colombia has experienced since the last century. The first is Colombia’s exceptionally difficult geography. The second involves the failure of the country’s political leaders and their followers to design effective institutions of government and make them work.

In their outstanding survey of Colombian history, published last year and entitled Colombia: Fragmented Land, Divided Society, Marco Palacios and Frank Safford argue that “spatial fragmentation…has found expression in economic atomization and cultural differentiation. The country’s…most populated areas have been divided by its three mountain ranges…into isolated mountain pockets…that fostered the development of particularized local and regional cultures, regional antagonism and local rivalries…”

Because of its geographic fragmentation, much of rural Colombia did not come to be settled until well into the twentieth century. As Palacios and Safford point out, these internal “frontiers” remained virtually stateless for decades. As in other frontiers, the lack of effective mechanisms for the enforcement of basic property and civil rights promoted violence. Vigilantes, private police working for big landowners, peasant and community defense organizations, local mafias and clans all proliferated and fought each other.

Why did Colombia’s internal frontiers remain virtually lawless and stateless for so much longer than other frontier regions? Two reasons stand out among many. First, imposing orderly government and providing minimal services like police protection, a functioning judiciary, schools, and the like is more costly in Colombia’s difficult terrain than in most other countries. Second, Colombia’s political institutions developed in a way that promoted the development of political parties as substitutes for government.

For much of Colombia’s history, local violence was linked to the two main political parties, the Conservative and Liberal parties. Until the 1991 Constitution, 20th-century Colombia operated under rules that gave the president of the country the right to appoint all local and state executives. Local and state legislatures, however, had to be elected every two years. The result was a lethal combination of mayors and governors appointed from Bogotá facing noisy and potentially disruptive local legislatures.

The president’s appointees often struggled just to control the urban areas assigned to them. Outside the main cities, and especially in recently settled areas, government barely functioned, with local people left to fend for themselves. In many areas, the two traditional parties fought for control, often violently. They forged links to local interests, recruited allies, developed or absorbed existing patronage networks, and merged with local mafias and clans. Villages and towns came to be identified as either Liberal or Conservative territory. The areas of internal colonization and frontier lawlessness coincide with the areas of modern guerrilla and paramilitary activity.

Many other problems contributed to the chronic violence of the Colombian countryside, including poverty and inequality. Historians also cite Colombia’s Catholic Church as another polarizing element. The Church resisted modernizing trends longer in Colombia than elsewhere; it was staunchly reactionary, wedded to the Conservative Party, and opposed to the separation of church and state as well as public education until the 1960s and 1970s.

Amazingly, over the past half century, Colombia has managed to achieve steady economic growth at a moderate pace, neither as high as the Asian tigers nor as anemic as most other Latin American nations. A modern Colombia of middle classes and urban sprawl thus grew and prospered, despite endemic rural violence. When conditions deteriorated enough to have an impact on life in the cities, as they did from time to time, unhappy urban voters compelled political elites to do something. The most significant of all such efforts, occasioned by the Drug Wars of the 1980s, was the adoption of a new Constitution adopted in 1991, which democratized local and state government by making mayors and governors subject to election for the first time in more than a century.

Unfortunately, the new Constitution did not calm the country, for two reasons principally. First, by the time the Constitution was adopted, the Drug Wars of the late 1980s had nearly destroyed the country’s judicial and law enforcement institutions. Second, the Colombian government had lost credibility as a partner in peace talks with armed guerrillas.

From the 1970s to 1985, chronic violence, especially in the countryside, kept Colombia’s homicide rate in the range of 20-39 per 100,000 population, high by international standards, but not much above Brazil and Mexico. Then the leaders of the drug cartels began a campaign of terror and assassination, aimed at stopping the extradition of drug trafficking defendants from Colombia to the United States for trial. They also redoubled their efforts to undermine the police and courts through bribery and threats. Colombia’s homicide rate soared to 57 in 1985, 86 in 1990 and 95 in 1993. In the Department (province) of Antioquia, which includes the city of Medellín, the homicide rate oscillated between 245 and 400 per 100,000 in the early 1990s. The high murder rates coincided with rapidly increasing rates of all kinds of crimes against property and people as the criminal justice system nearly collapsed. The new constitution could not repair this damage.

Among those who lost their lives in these years were more than 3,000 candidates for public office, including a major presidential contender. Most of those killed were former guerrillas who had accepted a government peace offer, laid down their arms, and agreed to seek peaceful change through the ballot box. Most were assassinated by right wing paramilitary groups, some of whom were collaborating with serving officers and units of the Colombian military or police agencies. The government’s failure to protect these former guerrillas running for elective office cast a pall on all subsequent negotiations with rebel groups: another key problem that the new constitution could not solve.

The Constitution of 1991 did help to end the Drug Wars by prohibiting extradition. The government then negotiated the surrender of several key drug cartel leaders by agreeing to give them light sentences served in comfortable surroundings in exchange for their pledges never to engage in drug trading again. But just as the Drug Wars ended, the guerrilla wars heated up.

The two main guerrilla organizations, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN), are believed to have benefited from the collapse of law enforcement and the break-up of the drug cartels. Both are said to have provided protection for a new generation of drug producers and traffickers in exchange for taxes and contributions running in the hundreds of millions of dollars each year. They began paying their soldiers monthly salaries and re-equipped them with the best weapons available on the international arms black market. The right wing paramilitary forces are said to rely even more heavily on income derived from drugs.

The United States could help to reduce violence in Colombia by decriminalizing production and sale of prohibited substances to adult consumers. Though unlikely to happen any time soon, such a step would take most of the high risk super profits out of the drug trade and deprive the guerrillas, and especially the paramilitary forces, of their means of financing their activities. Instead, the United States has opted to provide military assistance to the Colombian government to balance the help provided indirectly to the guerrillas and paramilitary groups by U.S. consumers of cocaine and heroin. This strategy calls for intensifying the violence on the theory that the government can win, or at least drive the rebels to negotiate seriously.

The new Colombian president Álvaro Uribe also appears determined to intensify the war against the guerrillas. He has also demanded that the paramilitary forces disarm. It is impossible to predict how effective these new military offensives will be. But Colombia’s history makes it clear that military victories have never addressed the deeper roots of violence and have thus provided little more than brief respites. To build a peaceful country, Colombians will need to face at least three difficult sets of issues, none easy to address amid violent conflict.

The first issue is how to defend and even restore human rights as the violence intensifies. It is possible for governments to win guerrilla wars by making more effective use of mass murder and brutality than their opponents. This is what the historian Tacitus had in mind when he said of Rome’s conquests in Gaul, “They make a desolation and call it peace.” As other Latin American cases have amply demonstrated, the dynamic of desolation is hard to stop or even to modify. Yet Colombia’s government will not have solved the nation’s historic problem of endemic violence unless it can create institutions that effectively protect human, civil, and property rights.

The second issue is how to create, strengthen and institutionalize effective democratic governance throughout Colombia. If the current strife were to end as all others in Colombian history have ended, with exhaustion and bitterness, but without a firm commitment to the costly but indispensable task of creating truly effective and broadly representative governing structures that function everywhere, the homicide rate will not fall below Colombia’s chronically high levels of the past, and new episodes of acute violence will follow again sooner rather than later. Essentially, Colombia’s urban middle classes and elites will have to signal a new and unprecedented willingness to pay the huge costs of creating a modern nation—rather than the shaky archipelago of modern cities surrounded by an ocean of neglect that exists now.

The third and final great issue is how to strengthen and engage civil society in the effort to restore and consolidate peace in the country. The fact is that Colombia already has an active, indeed, a hyperactive and engaged civil society. In fact, violence throughout Colombian history has come in large part from the activities of non-governmental civil society organizations, from political parties and vigilantes to paramilitary groups and drug cartels. Creating opportunities for Colombia’s vibrant civil society organizations to play a constructive and significant role in making peace in the midst of civil strife may be the most difficult, but possibly the most important challenge facing the Colombian government today.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.

Editor’s Letter: Colombia

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American…

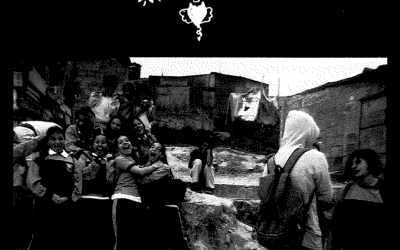

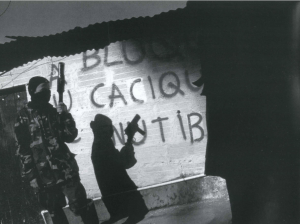

Photoessay: Shooting for Peace

Photoessay: Shooting for PeacePhotographs By The Children of The Shooting For Peace Project As this special issue of Revista highlights, Colombia’s degenerating predicament is a complex one, which needs to be looked at from new perspectives. Disparando Cámaras para la...