Sacred Dance in the Peruvian Highlands

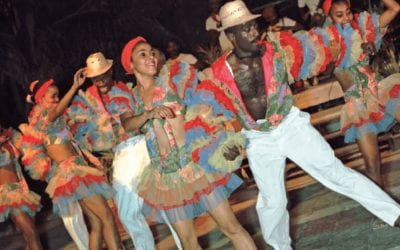

Scenes from the festival in honor of the señor de Qoyllur rit’i in the Peruvian highlands. Photo by Nicola Ulibarri

Long ago, a young shepherd named Marianito Mayta lived in the mountains above Mahuayani, caring for his aging father and tolerating the abuse of his lazy older brother. One day, a boy appeared who began to help Marianito with his chores. The Ocongate priest soon learned of this strange boy, whose white garments never ripped or stained, and, accusing him of stealing clothing from the church’s saints, decided to catch the rogue. After two failed attempts, the priest finally cornered the boy on the snowy mountainside, but he grasped a crying man with blood dripping from his hands. This was the first miracle of the Señor de Qoyllur Rit’i, which means “snow star” in Quechua.

The festival in honor of the Señor de Qoyllur Rit’i began as a small pilgrimage, when farmers and herdsmen from the Ocongate area journeyed to the santuario at the base of a three-mile-high glacier to pay homage to their local apparition of Christ. Today, tens of thousands of men and women from throughout Peru gather the weekend before Corpus Christi for three days of non-stop dancing, music and penitence. My Ocongateño host “father” invited me to accompany his son’s comparsa, or dance group, on the pilgrimage. It was the most exhausting, thrilling, nerve-wracking and fascinating three days of my summer.

Comparsas—Catholic brotherhoods of dancers and musicians—are the central participants in Qoyllur Rit’i. There are a limited number of dances, each telling a specific story about Peru’s history, and each town or village around Cuzco has one or two comparsas that perform the same dances year after year. I joined the Aucca Chilenos from the town of Urcos, who perform the story of lower-class soldiers and wealthy, white Peruvians during the War of the Pacific. The hermanos are ordinary people—teachers, farmers, policemen—who share a deep love for Christ, which imbues their dancing with a very genuine feeling. Though the dancers occasionally miss a step or do not dance with perfect carriage, every movement expresses an earthy sincerity.

I slept for a total of one hour during the three days of the festival. There was constant music, often with several different bands playing competing tunes. Explosions and fireworks sounded every several minutes, even at two or three in the morning. Comparsas would start dancing anywhere and everywhere: on the climb up the glacier, in a boggy field, in the courtyard below the church. Quechua masses were broadcast over loudspeakers from the sanctuary throughout the day. And Pablos, men dressed in bear costumes, whistled and danced through the crowds to whip anyone caught drinking, fighting or otherwise degrading the holy festival.

Although the twenty-four-hour commotion was overwhelming for me as a newcomer, the chaos has purpose. By dancing themselves to exhaustion, wearing insufficient layers for the freezing weather, and not sleeping for three days, the dancers perform penance for the Señor. As a fellow “Chileno” dancer told me—after we spent a numbing overnight vigil on the glacier—cold, hunger, fatigue and thirst are all imaginary, and that by suffering through them one becomes stronger in God’s name. Many dances include a section where the performers whip one another, another way of showing their willingness to suffer like Christ.

On the last night of the festival, as we hiked by candlelight throughout the night in a line that snaked for kilometers to reach Ocongate, I—an agnostic, female norteamericana—was baptized and whipped as a full member of the Aucca Chilenos. At sunrise, thousands of dancers, still clad in their masks and costumes, danced zigzagging across the hillside to mark the arrival of the statue of the Señor. Then the image was carried downhill to the church in Ocongate, and the men and women of the comparsas returned to their everyday life, at least until next year.

And, in order to fulfill my duties as a Chilena, I now have to return at least two times to dance in the Andes at the Santuario del Señor de Qoyllur Rit’i.

Nícola Ulibarrí (’08) spent three months in Ocongate, Peru, researching how development, agrarian reform, and “modernization” have influenced the residents’ sense of place, with funding from DRCLAS and the Goelet Fund. She is a senior in Currier House studying Social Anthropology.

Related Articles

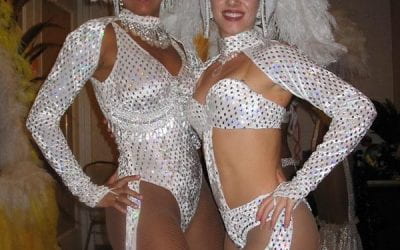

My Time as a Brazilian Passista

Although my behind is not all that curvaceous and I lack melanin in my skin tone, I somehow managed to pass for as a mulata passista. I am neither mulata nor a trained passista—a young woman, generally with a tiny outfit and curvy physique, who usually dances in front of the bateria during Rio´s carnival parade. I was a Harvard sophomore studying abroad in Rio de Janeiro and my training in ballet, modern and world dance had …

Disabling the “Tourist Gaze”: Protecting and Projecting Cultural Heritage through Dance

We hurried along the slim embankment on the bohemian side of the river as night fell in the city, nervously evaluating our distance from the dimly lit bridge that would carry us to a more cosmopolitan borough. Imagining the theater’s great gilded doors slammed closed before our arrival in the famed sixth district, we struggled to increase our pace, forsaking many sidewalk cafés en route to the night’s festivities but our stiff, …

Dance and the Cold War: Exports to Latin America

It was November 1954 in the middle of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. The Soviets had been investing heavily in exporting their artists, and U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower was convinced we needed to compete in that arena. In November 1954, the José Limón Dance Company was sent by the State Department to perform in Latin America, thus launching the first government-sponsored …