A Review of Santiago’s Children: What I Learned about Life at an Orphanage in Chile

A Journey South: An Excerpt from the Foreward

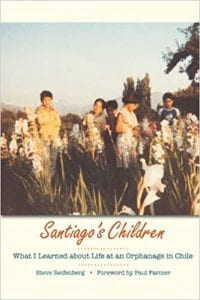

Santiago’s Children: What I Learned about Life at an Orphanage in Chile By Steve Reifenberg University of Texas Press, 2008, 226 pages.

There are five reasons I jumped at the chance to write a preface to Steve Reifenberg’s memoir about living and working in the early 1980s in a home for Chilean children who would otherwise have ended up in a large institutional orphanage. Five reasons, five areas of curiosity, five questions.

First, anyone who works in countries with many orphans—in places where young parents are apt to die—needs to know more about how best to raise these children humanely. You don’t have to read Dickens to doubt that large orphanages would be the best way to raise, for example, the millions of AIDS orphans now living in some of the places where I work as a physician.

A second reason I wanted to read Santiago’s Children was because I knew that its author had had an experience similar to mine: after college, Reifenberg set off for a country far from home, a troubled but beautiful place in which he became engaged in a noble enough task. He found himself helping run, under the guidance of a remarkable Chilean woman opposed to “the warehousing of children,” a group home for a dozen poor children. I expected to read a lyrical account of two often frustrating and sometimes emotionally wrenching years, the story of a journey south to a place he didn’t know, a journey with and among people, most of them children, who had known none of the security he’d enjoyed in a rock-solid, middle-class American family. Epiphany, or at the very least illumination, seemed sure to follow. I wanted to know more about Steve Reifenberg’s coming of age and to compare notes.

I knew that Steve—“Tío Esteve” to the Chilean children and to the tiny band of their fearless adult protectors—had arrived in Santiago, the tumultuous capital city, at a fairly harrowing time in Chile’s history. So, third: How would Chile’s political crisis figure in so personal a memoir? Coming a decade after the 1973 coup that put an end to Chile’s experiment with democracy, Steve’s tenure occurred at the time of a devastating economic downturn, a time of police interrogations, a time of curfews and mean military repression of demonstrations, often using deadly force.

Fourth, would this be a good book to use in teaching? Scholarly treatises and historical accounts of difficult times rarely try to capture the everyday feel, the gritty anxiety of living on the edge, financially, with a dozen children to look out for; academic accounts are not good at rendering the texture of everyday life as violence and repression intrude. Teaching about the travails of democracy in Latin America is difficult to do when we are left to choose between shrill polemic, superficial journalism, and dry, experience-distant accounts. Steve Reifenberg was both an eyewitness and an externally placed observer, and he also learned a good deal about what was happening in Chile from human rights materials gathered from his own country.

Finally, I knew that the book had been conceived in journals written more than twenty years ago. But Reifenberg had finished Santiago’s Children much more recently, back in Santiago, where he once again lives and works as director of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies’ Regional Office. I was dead curious to see if he’d been able to follow the fates of all the children one would get to know in the telling. What were they all up to now? What relationship did this dark Chile of the early 1980s have with the impressive, if uneven, advances of Chile today?

Santiago’s Children is immensely satisfying on all five scores: for young Americans—and for young people from many other places who find themselves able, through the luck of the draw and accident of birth, to travel to places like Chile or Haiti or Rwanda—this memoir will serve as a gentle and self-deprecating guide book. What happened to its author, the ways he grew and learned more about his strengths and weaknesses, are all there. The book is pitch perfect, as far as humor and detail go.

First, there are the children. You get to know them and to see them grow. Reifenberg spent two years as a surrogate parent and teacher in the orphanage. Some of the kids were right off the street; some had been abandoned by a parent not able to get by; others were orphaned by political violence or by the grinding violence of poverty and economic crisis. Reifenberg lets us know what it’s like to try and prepare more than a dozen kids for school each morning, or what it feels like to try, twice, desperate for money, to launch a family farm only to see the water cut off or, worse, your newly acquired draft horse die before the field is fully plowed. We see how tempers sometimes flare in tight quarters, sense the anxiety that accompanies a trip to the beach in charge of a dozen unruly kids. And always, there is the narrator’s frustration at not mastering Spanish quickly enough, often to the amusement of the kids and neighbors.

Through these stories, we actually get to know a dozen children. The portraits are built piecemeal, but by the end ofSantiago’s Children we’re left with the characters: irrepressible Carlos and his brother Patricio, whose father is in jail and whose mother cannot take care of them; studious and preternaturally mature Verónica; naughty and irrepressible Marcelo; Andrés, a boy who can be relied on to carry out any threat or whose fear of horses is born when the doomed draft horse nips him prior to going to her great reward; Big Sonia, the amateur philosopher “So, why do they always call God a he? It makes me furious!” And quiet Karen whose occasional utterances surprise Steve.

Reifenberg is careful to focus on the children themselves in the first half of the book. But as the book moves forward easily, and with a great deal of humor, political violence seeps into its pages. By that time the reader is a fierce partisan of these children and their neighbors, who live in a poor part of town. What is the narrator to do with the entreaty, from one of the mothers of the thousands of “disappeared” young activists, that Steve, the American, help her to find her son? The wave of disappearances laps frighteningly close to the home. By the latter half of the book the constant attack on civil and political liberties is as expertly blended into the text as the household struggles for access to the one bathroom and the arguments about who’s going to do what chores. In finishing the book, we discover we’ve learned a good deal about Chile.

As Reifenberg later discovered at Harvard, so many students are trying to figure out how to make a contribution in some meaningful way. We’re all liable, especially when young, to undertake quests hoping for a personal sense of self-efficacy—to feel that we’ve made a meaningful contribution. Through his book, we see him coming to understand just how huge the obstacles are. The book is also honest about the frustrations. Surrounded by lives trammeled by poverty and repression, he begins to see just how privileged and protected our lives in North America have been. More honestly still, Reifenberg traces the links between our own privilege and the privations of others. In the case of Chile, these connections are direct and damning.

Steve Reifenberg’s central message, though, is optimistic, encouraging. The effort doesn’t have to be Herculean, he seems to be telling an audience contemplating great deeds in far-away places. A big step in the quest is taken, simply enough, by investing time and energy in something decent and then sticking with it. It’s important to be willing to engage in things you care about, even if those efforts do not always lead to obvious victories, and to continue learning in the process.

For this reason, especially, the book will be a wonderful resource for students, young and old. I now teach mostly medical students and physicians, but in my experience, their concerns are not very different from those Steve felt, as did I. It’s hard to imagine someone who finds himself an outsider in one of the tougher neighborhoods of Latin America or Africa or other “foreign” parts of the world—or someone interested in learning about one of those places—who would not find this book immensely instructive and moving.

Santiago’s Children reminds us that even modest efforts, like those of Steve Reifenberg, might at least palliate the pain encountered in a place like Pinochet’s Chile. Certainly efforts such as his, and the lessons drawn for this kind of international experience, would be preferable to the current, ham-fisted approach to U.S. foreign policy and to the conventional development enterprise. Often these policies are steered, and none too gently, by economic ideologues who don’t often apologize when they make yet another about-face whose costs are borne by others. I can’t help but wonder what might have transpired if we’d approached these same problems and policies with the good will, humility, and the willingness to learn that runs throughout this book.

Paul Farmer, Medical anthropologist and physician, is a founding director of Partners In Health and the Presley Professor of Medical Anthropology in the Department of Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School. He has written extensively about health and human rights, and about the role of social inequalities in the distribution and outcome of infectious diseases.

Related Articles

A Review of Live From America: How Latino TV Conquered the United States

The story of Spanish-language television in the United States has all the elements of a Mexican telenovela with plenty of ruthless businessmen, dashing playboys, sexy women, behind-the-scenes intrigue and political dealmaking.

A Review of The Power of the Invisible: A Memoir of Solidarity, Humanity, and Resilience

Paula Moreno’s The Power of the Invisible is a memoir that operates simultaneously as personal testimony, political critique and ethical reflection on leadership. First published in Spanish in 2018 and now available in an expanded English-language edition, the book narrates Moreno’s trajectory as a young Afrodescendant Colombian woman who unexpectedly became Minister of Culture at the age of twenty-eight. It places that personal experience within a longer genealogy of Afrodescendant resilience, matriarchal strength and collective struggle. More than an account of individual success, The Power of the Invisible interrogates how power is accessed, exercised and perceived when it is embodied by those historically excluded from it.

A Review of Negative Originals. Race and Early Photography in Colombia

Negative Originals. Race and Early Photography in Colombia is Juanita Solano Roa’s first book as sole author. An assistant professor at Bogotá’s Universidad de los Andes, she has been a leading figure in the institution’s recently founded Art History department. In 2022, she co-edited with her colleagues Olga Isabel Acosta and Natalia Lozada the innovative Historias del arte en Colombia, an ambitious and long-overdue reassessment of the country’s heterogeneous art “histories,” in the plural.