Securing the City

The Politics and Business of Postwar Security

Guatemala is experiencing a new economic stimulus: the security industry. The internal armed conflict may have ended more than a decade ago, but everyday life for many Guatemalans continues to be fraught with violence. The country has one of the highest homicide rates in the Americas (about seventeen murders per day) and one of the lowest rates of incarceration. The average criminal trial lasts more than four years with fewer than two out of every hundred crimes resulting in a conviction. As one international observer remarked on the BBC News in 2007, “It’s sad to say, but Guatemala is a good place to commit murder because you will almost certainly get away with it.” Postwar peace now seems little more than a bloodied banner.

The number of private security guards working in homes and businesses is now estimated at 80,000, compared to 18,500 police officers nationwide, according to the U.S. Agency for International Development.

The employment of private security forces by businesses and individuals is just one of many responses to escalating crime and violence. Other private solutions include the formation of community associations and, in the most extreme cases, vigilantism and lynching, as well as the growth of gated communities to keep violence out. These responses represent a new trend: instead of being a public right, law enforcement has largely migrated from state institutions to the private sector. Indeed, the growth of private security firms in the last decade is astounding.

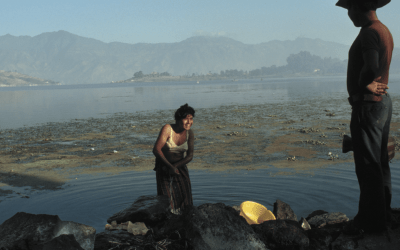

In a recent study, Avery Dickins de Girón, an anthropologist at Vanderbilt University, shows that a growing number of rural Guatemalans have come to see private security work in the capital city as a viable, albeit dangerous, option for upward mobility. Over the last century, changes in rural areas have led to several waves of migration into Guatemala City. Economic restructuring since the early 1990s exacerbated this trend, undermining what remained of the subsistence farming system upon which rural inhabitants historically relied. For an increasing number of Maya men moving into the city, finding work in private security is an attractive prospect.

Security guards from the department of Alta Verapaz, just north of the capital region, are generally landless indigenous men from impoverished communities. They seek work as guards por necesidad (out of necessity), hinting at the structural conditions of poverty and unemployment in their hometowns. These men provide a flexible, low-wage workforce for the hundreds of authorized and unauthorized security firms operating in Guatemala City. Generally viewed by their employers as expendable laborers, they are housed in substandard conditions and paid relatively low wages for what can be a deadly job. At the same time, the men use the flexible nature of this work to their advantage. Working when they need cash income to supplement other earnings, they quit when the exploitative conditions or dangers of the job become too much to bear. They may only take a short break before continuing security industry work, or they may attempt to capitalize on social networks in the city to move into a more desirable occupation. Many of the men with whom Dickins de Girón spoke reported that employment in the security industry offers a chance for them to experience both the best and worst of urban life. Excitement and opportunity draw them to the city. At the same time, discrimination, exploitation and dangerous conditions characterize their migrant experience.

The private security industry is perhaps the most obvious example of how citizens respond to growing fear in Guatemala City. A more understated but nonetheless related trend is the growth of urban renewal projects, aimed at creating safe enclaves for middle- and upper-class residents. Clusters of private condominiums, shopping centers and entertainment districts cocooned by guns, dogs and guards now speckle Guatemala’s highways. Fortified enclaves segregate Guatemala City’s exclusive zones from the more popular ones. Zone 1, for example, is the capital’s oldest and most historic zone, home to the national cathedral, high courts, and national palace. Anthropologists Rodrigo J. Véliz and Kevin Lewis O’Neill note that Zone 1 has become dangerous in recent years, with a disproportionately high rate of violent murders taking place there. Upper classes have relocated to peripheral zones built up over the past two decades. These areas comprise fortified homes, upscale shopping malls and protection by private security forces.

A number of wealthy Guatemalans are trying to reclaim Zone 1, however. Plans include ridding the historical city center of less desirable elements, including street vendors and the working-class clients who depend on their cheap goods. The program would create heavily secured retail and recreational spaces where the city’s elite can engage in forms of conspicuous consumption that are well beyond the reach of many Guatemalans. Although Zone 1 street vendors have organized, staging a series of protests and engaging in negotiations with the government planning commission, redevelopment plans continue to move forward without them.

One might expect that the spike in violence seen over the past decade would prompt public debates about the social and economic conditions that permit violence to thrive in the first place. By and large, this has not been the case. Responses to urban crime such as private security forces and urban renewal projects address only the immediate security concerns of the most affluent segments of the population.

On a national level, political strategies that exploit themes of personal insecurity and fear have defined the conversation.

The most prominent political feature of the post-conflict period has been the popular call for mano dura (strong hand or iron fist) solutions to violence. Otto Pérez Molina, a former military general, ran on this platform in the 2007 presidential election. He won handily in the metropolitan region and, at the national level, finished a very close second to Álvaro Colom, whose left-centrist platform helped him to carry the rural regions.

Mano dura politics makes use of two-dimensional caricatures. Criminals and other unsavory social types, including gang members, are posited as the source of violence rather than as the effect of structural conditions. USAID estimates put the number of gang members nationwide at anywhere from 14,000 to 165,000. Although the wide range of this estimate reflects a lack of solid data on (or even a commonly accepted definition of) gang activity, gangs nonetheless shoulder the blame for the nation’s security problems. Proponents of the mano dura approach tend to couch security concerns in moral rather than material terms. They lament widespread problems of delinquency and cite character faults among the nation’s youth as key social issues. The most obvious and alarming public responses to these problems include military intervention and social cleansing campaigns. More subtle, yet perhaps more sinister responses include outreach programs in which security officials and development workers focus on changing young people’s attitudes and building their self-esteem. The latter response personalizes postwar security concerns, shifting the focus from structural conditions to issues of individual character and responsibility.

The structural conditions for so much postwar violence are as predictable as they are painful: the widespread availability of arms, government corruption, lack of police protection, and organized crime linked to the drug trade. Violence is also rooted in a set of social and structural conditions that limit life chances for many Guatemalans. In terms of the most basic of social services, much of the capital city has simply fallen off the grid. Lack of sufficient housing, limited access to water and sanitation services, and vulnerability to environmental hazards characterize life for many residents who live in high-crime zones and the urban periphery. Many residents also rely on an unstable, informal economy and face institutional and everyday forms of discrimination, especially when it comes to indigenous people, women and the poor.

Mano dura responses to rising crime rates and other security concerns look quite different from the sweeping social, economic and political promises made in the 1996 Peace Accords. The peace negotiations, it was hoped, would usher in a new era of democratic process and economic growth. Disparate groups sat at the table to voice their concerns and contribute to a new vision of Guatemalan nationhood and the realization of new opportunities for employment, education and entrepreneurship. The accords included important endorsements of human rights in general and indigenous cultural and political rights in particular, including education reforms to enhance rural achievement and political reforms to expand civil society. As scholars have repeatedly pointed out, however, increasing disparities have defined the post-conflict era, and these disparities have diminished the prospect of full democratic participation of all citizens.

The shortfalls of the Peace Accords are rooted in the structural conditions of discrimination, inequality and corruption that post-conflict economic policies and institutional reforms have failed to address. In fact, policy approaches in the last decade have actually permitted the escalation of violence beyond war-era proportions, with the annual number of homicides now exceeding the average number of Guatemalans killed each year in the internal armed conflict. Violence is not new to Guatemala, but its spatial coordinates have now shifted from the rural highlands—the scene of the scorched earth policies of the 1970s and 1980s—to the streets of Guatemala City. The kinds of violence taking place in Guatemala and public responses to it have also changed. The state no longer controls either the means or aims of force. Instead, public agencies and private individuals employ violent means for a variety of ends, including political and economic gain. The personalization and individualization of security through the language of delinquency allows politicians, the media and ordinary citizens to simply point fingers.

A more effective set of responses would address the conditions of poverty and inequality that make everyday life difficult for most Guatemalans, as well as the criminal organizations and corrupt political institutions that foster violence and benefit from popular discourses that focus blame on street gangs and poor youth. Official and popular narratives that do not address these conditions will likewise continue to neglect the promises of peace.

Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1

Related Articles

Guatemala: Editor’s Letter

The diminutive indigenous woman in her bright embroidered blouse waited proudly for her grandson to receive his engineering degree. His mother, also dressed in a traditional flowery blouse—a huipil, took photos with a top-of-the-line digital camera.

Making of the Modern: An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann

Making of the Modern An Architectural Photoessay by Peter Giesemann Fall 2010 | Winter 2011, Volume X, Number 1Related Articles

Increasing the Visibility of Guatemalan Immigrants

Guatemalans have been migrating to the United States in large numbers since the late 1970s, but were not highly visible to the U.S. public as Guatemalans. That changed on May 12, 2008, when agents of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) launched the largest single-site workplace raid against undocumented immigrant workers up to that time. As helicopters circled overhead, ICE agents rounded up and arrested …