Seeking Higher Ground

Dispute Resolution and Resettlement in Ceará

Plans to build Castanhão, the largest dam in Ceará, Brazil, have existed for a century. Incredulous that the project would ever begin, much less be finished, residents of the proposed flood zone continued with their daily lives, building and formalizing communities along the banks of the Rio Jaguaribara. Here they built social, economic and legal ties to the land—ties that in the late 1990s had to be severed.

By 1998 anti-dam community leaders realized that stopping the dam was no longer an option. They acknowledged that their strategies must change, and the best they could do is work, and if necessary fight, with the government for their rights to resettlement on higher ground. They used every possible tool at their disposal from established institutions such as the Catholic Church to newly formed international solidarity networks, from face-to-face community meetings following Mass to Internet and fax communications to the World Bank president. Through the new state government mandated dispute resolution process instituted for Castanhão, referred to as the GM (O Grupo de Trabalho Multiparticipativo), they learned to know whom to pressure and why, how to make alliances with groups with whom they have had little previous contact or affinity and to evaluate whom to trust.

Meanwhile, as the concrete and water rose, so did the expectations of the Brazilian national and state administrations. International solidarity networks were pressuring the World Bank, and Castanhão had become an issue. Although the Bank didn’t fund the project, it was funding other smaller scale state water projects through PROGERIRH and PROURB programs. It and its state level counterparts knew that what happened in Castanhão would effect what happened in the rest of the state: socially, politically and financially. However, they were not the only ones who knew this. A soft-spoken and extremely well organized nun with a jeep, computer and printer living in the parish of Jaguaribara also knew this, and this is where our story begins.

LOVE THY ENEMY

We left the parish house located in front of the Jaguaribara Catholic Church, the same one we had seen in the pictures that would be replicated for the new city, Nova Jaguaribara. We walked down the cobblestone streets to our first meeting with the local Resident’s Association. Local leaders had chosen the building since it was the only one with air-conditioning. Although the rest of the sertão was stiflingly hot because of the nine- month drought, this town, built lower down by the river was relatively green. At night people moved tables and chairs out onto the sidewalks to sit, drink, play cards, talk and enjoy the evening breeze. But that would all stop soon, once construction on Castanhão was complete.

It was 1998 and I was on my first tour of Castanhão’s flood affected areas, one of many visits over the next decade. I was the social scientist in a research evaluation team assessing government resettlement practices among communities to be displaced by dam projects aimed at combating regional drought. Although less dramatic than earthquakes, hurricanes or tsunamis, to Brazilian policymakers drought was the cyclical natural disaster that unrelentingly plagued their country, defining the past and future of all those living within the “drought polygon.”

We had come to Jaguaribara to meet Sister Maria Bernadette Neves. Active in building community organizations for 17 years, she was the leader of the local movement against dams and advocate for the impacted communities. We had heard a great deal about her leadership in opposition to the dam, meetings with Medha Patkar of the Indian Narmada Bachoa Andolan (NBA), and role in the Brazilian Movement of People Affected by Large Dams (MAB). Although disliked by some extension workers, most pro-dam advocates praised her as a woman of great intelligence, strength and organizational ability. She was a force to be reckoned with and institutional representatives all agreed should be the person we first meet upon entering the project affected communities. We were, however, unsure how this meeting would go. We were contracted by the Secretariat of Water Resources to study resettlement and rehabilitation (R&R) reform and had an interested audience at the World Bank. We had spent the last month interviewing state and private sector representatives and field technicians. Finding out we had strong contacts to the Bank had sparked a great deal of interest on the behalf of service institutions. How the communities would react to our presence was unknown.

After this initial meeting, Sister Bernadette approached a member of our group who was from India. She had learned a lot from Ghandi’s teachings, in particular to love thy enemy, she said. She was using his teachings in this struggle, here, now. My colleague added that other leaders facing similar situations had preached similar restraint. He told the story of how after one of the battles of the U.S. civil war, Lincoln was praising the bravery of the other side’s soldiers. Afterwards an old woman asked him why he would praise the enemy instead of putting all his energy into destroying them. Lincoln answered that “when I make them my friends, do I not destroy them as my enemies?” The message was clear: despite our different positions and interests, we were willing to work together, and, for now, that was good enough.

CULTIVATING NEOLIBERAL REFORMS

When we began fieldwork in May 1998, Tasso Jereissati was finishing his second term as governor and preparing for October elections. The Northeast was experiencing another bad period of drought, sparking new waves of urban migration, and rending the agricultural economy and rural population “inactive.” The state government just instituted emergency programs including food and emergency employment aid, similar to those implemented throughout the previous 100 years. Jereissati also accelerated the creation of state water resource infrastructure, making them integral components of development policy aimed at providing municipal water supplies to urban centers and irrigation for food production and agro-industrial initiatives.

Despite the economic hardship caused by droughts, economic growth within Ceará during the late 1980s and early 1990s outpaced the rest of the Northeast and the more “developed” parts of the country. International and Brazilian business reviews credited higher growth to the distinctly “probusiness” and “modernizing” policies of state level leaders (e.g., Jereissati 1986-90, 1995-99; Ciro Gomez 1991-94). While drought was familiar to Ceará, economic trends in which it performed well were not. The Brazilian Northeast, composed of nine states, encompassing one fifth of Brazil’s landmass, and home to 30 percent of the nation’s population is one of its poorest regions, producing only 14 percent of GDP. Despite its primacy during the colonial period and in national culture, the Northeast has been viewed throughout the twentieth century as a national liability: the source of rural out migration to the cities in the South and Amazon basin and a continuous drain on national funds.

One of the objectives of water infrastructure development in semi-arid regions is to provide stable employment for rural producers, reducing migration. However, the creation of water infrastructure immediately dislocates people. International funders and planners impressed with Ceará’s reforms focusing on participatory planning and decision making, hoped that here they would find a new approach to resettlement. For them the question wasn’t “What has gone wrong again?”, but “How can an area famed for clientelism and poverty transform into a model of economic growth and ‘good government’?”

LOOKING FOR GOOD GOVERNMENT IN THE TROPICS

In 1997, Judith Tendler brought Ceará into the limelight, not as another example of corrupt systems and rural victims, but rather of “good practices.” In Good Government in the Tropics she challenged conventional Latin American development analyses by formulating advice drawing on cases of good performance; promising programs in rural preventative health, business extension and public procurement from small firms, employment creating public works construction and other emergency relief and agricultural extension services. These revealed a three way dynamic between activist central governments, local governments, and civil society, in which the state contributed “to the creation of civil society by encouraging and assisting in the organization of civic associations and working through them. These groups then turned around and ‘independently’ demanded better performance from government, both municipal and central, just as if they were the autonomous entities portrayed by students of civil society” (Tendler 1997:16). This argument greatly “complicates the currently popular assumptions of one way causality, according to which good civil society leads to good government and, correspondingly, good government is dependent on the previous existence of a well developed civil society” (ibid).

Her argument raised questions in Brazilian Secretariats, U.S. and Brazilian NGOs and the World Bank. Beyond its conciliatory stance towards Northeastern reform and extension workers it made sense to those familiar with policy making and funding. Individuals within these administrations knew that decision making regarding water resource allocation was far from unidirectional; NGOs were not disinterested transparent mouthpieces of the masses, and the state wasn’t always right. Current social programs were the result of initiatives made by various actors that constituted a dialogue dominated by shifting priorities. The question was, “Was this happening in Castanhão?”

GIVING CREDIT (AND LOANS) WHERE IT’S DUE

Much of the organized resistance to the Castanhão project and organizational success of Jaguaribara was led and coordinated by Sister Bernadette. When she first arrived in 1981, the socio-economic conditions and organizational level of the municipality mirrored those of surrounding areas. Since then she helped organize to improve conditions, creating a stronger presence of the Catholic Church in the city, improving schoolteachers’ wages, then spearheading demographic and socio-economic data collection in the municipality.

Although dam-building had been discussed since the early 20th century, concrete plans only began in 1985, when the state government had the political and financial ability to move ahead. This was when Secretary of Planning extension workers began visits to households marked for resettlement. They were met with great resistance, particularly in the town of Jaguaribara, being driven away with rocks and threats of violence. R&R over the previous 50 years in Ceará had left much to be desired and the communities feared a replication of Oros, the other dam on the Jaguaribe. PAPs often referred to stories of “dynamite” and “hydraulic resettlement” in which people were driven from their homes by construction blasts at the dam’s axis or by rising water.

Shortly after notification, Sister Bernadette began calling community wide meetings and helped to form a Resident’s Association in Jaguaribara City and two rural communities. These associations dedicated themselves to finding out more about the project, collecting and organizing vast quantities of information. Sister Bernadette and Resident Association leaders then built an extended network, first through the Catholic Church, and later through national and international solidarity networks of people affected by dams. This community resistance helped delay the dam for nearly a decade. However in 1994 work commenced at a serious pace and never ceased.

Winter 2007, Volume VI, Number 2

Jennifer Burtner is a Lecturer in the Department of Anthropology, Tufts University, and a Research Affiliate and Former Brazilian Studies Coordinator, DRCLAS, Harvard University.

Related Articles

Environmental Stress and Rainmaking

When Europeans first attempted to settle in North America north of the Rio Grande, their confrontations with Indian cultures were marked by cosmic struggles over environmental…

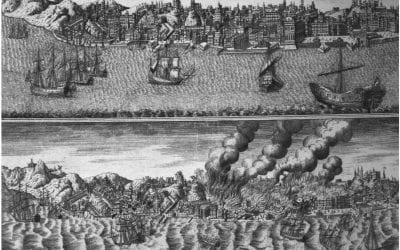

“Bury the dead and feed the living”

“Bury the dead and feed the living.” These were the words attributed to Portugal’s pragmatic, all-powerful first minister, the Marquês de Pombal, as he contemplated the damage wrought by…

The Jesuit and the Jew

Such a Spectacle of Terror and Amazement, as well as the Desolation to Beholders, as perhaps had not been equalled from the Foundation of the World.” Thus an English merchant writing…