Shamanic Tourism

Lessons for the 21st Century

Today it is hard to find someone who has not heard of the infamous hallucinogenic plant mixture called ayahuasca commonly prepared from the stems of Banisteriopsis caapi and the leaves of Psychotria viridis or chacruna. The brew, well known for its purging and visionary effects, is often sought by westerners for healing and personal transformation.

For decades, ayahuasca was the stuff of legend associated with, among others, the pioneer field ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes and beat authors Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs. Today, ayahuasca has spread globally through a number of religions, as well as the phenomenon of shamanic tourism. Unlike other mind-altering substances ayahuasca is still largely consumed in its original form and in a structured ritual setting. In the context of shamanic tourism, the experience often involves the participation in a shamanic dieta, a process involving fasting and ingesting nonhallucinogenic plants utilized by Amazonian shamans.

Winter 2021, Volume XX, Number 2

In 2002 I was a young graduate student beginning my fieldwork in the Peruvian Amazon on the ritual use of a hallucinogenic mixture that had fascinated me since I took my first anthropology of religion course at the University of Vienna. I was aware of the expansion of ayahuasca in different cultural contexts and during my exploratory trip to Iquitos, Peru, I first encountered the (at the time) budding ayahuasca tourism. Reluctantly, I included it in my ethnographic study, allowing it to become my focus when I began doctoral fieldwork in 2003. The nascent ayahuasca tourism that I encountered back then has in the last ten years developed into a full-blown tourism industry centered on numerous lodges that have transformed Iquitos to the mecca of shamanic tourism. Even though the ayahuasca experience is possible throughout the world—through participation in rituals offered by itinerant shamans—many tourists still take the expensive trip to South America to experience it at its place of origin.

Map of Ayahuasca Healing Retreats (Data sources: Esri World Countries shapefile, 2020; Google Earth Pro, 2020. Map author: Jessica Fisher, Kent State University Libraries, Map Library, Map It!, May 2020.)

Locals often call Iquitos an “island” because it cannot be reached by road; the only road, approximately 56 miles long, connects Iquitos to Nauta, a small town to the south. Many of the ayahuasca retreats that cater to tourists are on this road. In 2005, I estimated the number of people who travelled to Iquitos specifically to take ayahuasca to be in the hundreds every year. In the last five years this number is probably in the thousands, although there is no official tally. As an example of the transformation of the local economy, local restaurants offer “ayahuasca diet menus” to cater to the numerous tourists observing the restricted diet before and after ayahuasca retreats.

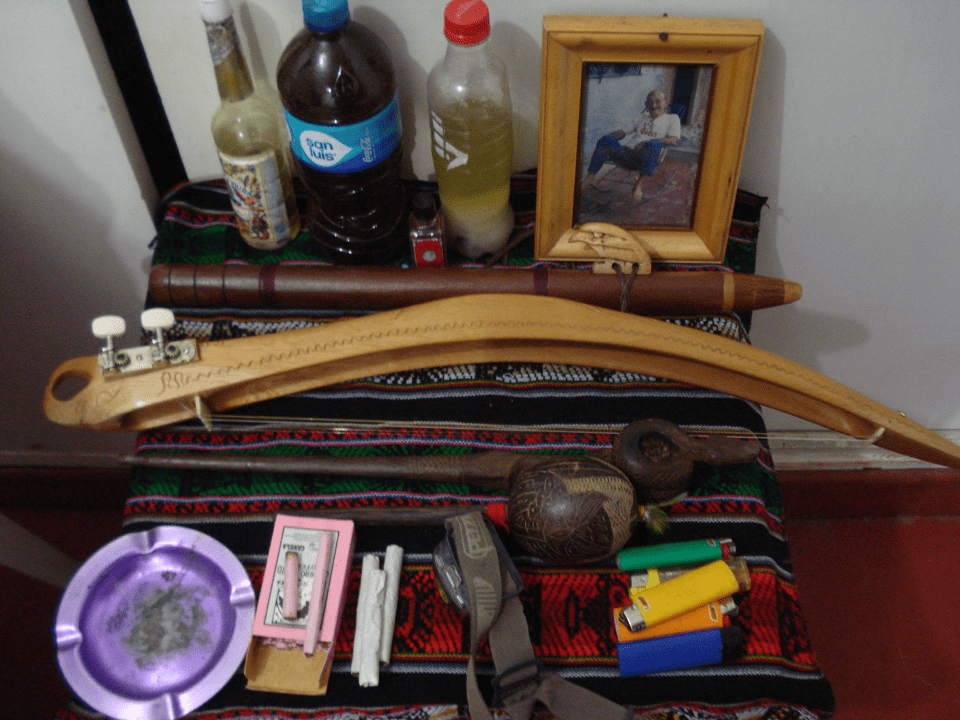

During my research, I focused on the motivations of the tourists, the ways they conceptualize their experiences, and how they integrate them in their lives. I also worked closely with nine shamans in the city of Iquitos or in retreats in the surrounding area. In addition to attending ceremonies, I observed the preparation of ayahuasca and was introduced to the local worldview regarding plants, healing, spirits and sorcery. While writing the results of this research, I realized that this was a study in contradiction, ambiguity and the liminal space between “worlds.” The biggest paradox I found is that although Amazonian shamanism in its current form likely emerged as a response to the violence and disruption of the rubber boom, today, westerners view ayahuasca as the healing force for disorders that stem from what is perceived as western cultures’ spiritual impoverishment.

Another paradox is the proliferation of shamans, as well as the strengthening of Indigenous identities. A few years ago, young people were not interested in apprenticing to become shamans. However, the possibility of a steady income provides a strong incentive, and many “new” shamans “graduate” only after a few months of apprenticeship. These “new” shamans are often more successful on the global market and gain prestige by working with tourists or traveling to lead ceremonies abroad. In addition, there are concerns about the effects of ayahuasca commercialization on health care in Amazonian communities, as more shamans prefer to work in tourism rather than healing members of their community.

A similar phenomenon took place in the Sierra Mazateca in Mexico which since the 1960s attracted westerners who wished to experience the exotic and divine other in the form of hallucinogenic mushrooms that symbolized the timeless natural world and the “good Indian.” The globalization of ayahuasca shamanism poses similar challenges, namely Amazonian peoples are often seen as spiritual and wise, holding the answers to global problems, while in reality they are embedded in larger struggles for sovereignty and survival. Interestingly, all this attention gives Indigenous peoples a platform to raise awareness about their struggles. Indigenous healers and activists are included in international conferences and the dialogue about the future of ayahuasca. At a virtual event (held during the Covid-19 pandemic), Indigenous representatives expressed the wish to exercise their agency as opposed to being mere “beneficiaries.”

Intercultural Translation in Shamanic Tourism

Shamanic tourism provides a fascinating intercultural space and several opportunities for reflection about our relationship to cultural “others” within a global landscape. While it provides an opening to radically different worldviews and s window to Indigenous knowledge systems, it also presents challenges as many things are lost in translation. The western interest in ayahuasca has shaped the discourse in particular ways in the last two decades. First, a therapeutic model has emerged within shamanic tourism and beyond. Ayahuasca and plants used in shamanic dietas that were traditionally part of a healer’s apprenticeship to build relationships with spirits and learn from them, are now being used as therapeutic tools. My data also reveals that spiritual pursuits are central among western participants, something that is not surprising considering the important role that psychedelics have played in the development of “unchurched spirituality.”

Most western participants seek ayahuasca with a desire to heal and in interviews have reported healing from psychological and physical ailments, particularly trauma and depression. People frustrated by the biomedical paradigm turn to shamanism, seeking more holistic and “natural” healing. This focus on healing has led to the sanitization of Amazonian shamanism from its darker aspects, such as sorcery. While sorcery—the practice of using supernatural means to harm another—has been a part of Amazonian shamanism, its importance is often downplayed in the context of tourism. During my research, I discovered that sorcery is very common in the Peruvian Amazon today and I was able to observe rituals performed to counter sorcery attacks. The shamans involved explained that one of the main reasons people employ sorcery is envy—most likely exacerbated by the sharp inequalities due to capitalism.

Westerners seek out ayahuasca because it provides direct access to the sacred and many have reported spiritual experiences with it. Ritual is fundamental in this process, and participants stressed that the structure of the ritual provides a framework for transformative healing and spiritual work lacking in western cultures. Scholars, such as psychoanalyst Carl Jung, have lamented the lack of magic and sacredness in western cultures. However, there are important differences between what is considered sacred or spiritual. In Indigenous cultures, there is a specific geography of the worlds shamans visit in their trance as well as relationships with spirits that they seek during their apprenticeship and maintain throughout their lives. In contrast, in a very Jungian manner, for most westerners the shamanic journey becomes a journey to the subconscious. While traditionally shamanism was a healing force for the community, in this context it becomes about healing the individual first with the ultimate goal of healing the collective. Likewise, the songs sang in ayahuasca rituals turned from language of the spirits to tools that guide the visionary experience. However, I did discover that westerners who engage with Amazonian shamanism for an extended time and apprentice with a shaman begin to interpret ayahuasca experiences as encounters with spirits.

Even though an array of literature exists on the topic, misconceptions about shamanism abound. In nonacademic writing, the historical and cultural context of shamanism has been ignored until recently. For many, participating in shamanic ceremonies connects them to an archaic past. This is evident in discourse about participating in something that has been practiced for thousands of years—despite the lack of evidence to support this. Shamanism is seen as timeless and universal and it is as though the past holds what the modern lacks. This often turns into primitivist discourse, especially because Amazonia is viewed as home to some of the last primordial peoples of this planet. By removing shamanism from its historical and cultural context, such discourse obscures the fact that it often gets reinvented as a local tradition within a global framework.

At the same time ayahuasca has become a marker of indigeneity, and some Amazonian ethnic groups use it as part of a strategy to recover or revalorize their traditions. This has led to a tendency toward hypertraditionalism in shamanic tourism. While Indigenous ayahuasca traditions are changing—for example, to include women—indigenous people are seen as the legitimate stewards of ayahuasca. Many happily embrace this label.

Nevertheless, there are several complications with the fascination with Indigenous spiritualities. Some particularities of Indigenous knowledge systems are being stripped as they become globalized. Global culture is often unable to capture the holistic nature of Indigenous knowledge because there is a lack of context for belief and application. Even though many western participants show a remarkable engagement with Amazonian shamanism, for the majority, the relationship is still superficial and transient as certain aspects of Amazonian worldview and ambiguous aspects of shamanism—such as sorcery—tend to be overlooked. I often wonder whether this contributes to the marginalization of Indigenous knowledge rather than its revalorization.

It is unclear what the future of shamanic tourism will be, as ayahuasca rituals are increasingly carried out away from the Amazon and several organizations are working on legalization of psychedelics in western countries. Ayahuasca was an unlikely candidate to become such a pervasive force, both because of the unpleasantness of the experience as well the distinct motivations of the users. These motivations are, from shamanic tourists’ or therapeutic clients’ viewpoints, more benign; nevertheless, tourists may unintentionally make shocking demands on local societies, set disruptive examples or saddle hosts with unwanted responsibilities.

Undeniably, discourse about Indigenous peoples in the context of shamanic tourism can be highly problematic due to the legacy of colonialism and the unequal systems of power it perpetuates. The globalization of ayahuasca often pushes local worldviews to the background and adapts the practice to the needs of westerners. The question is no longer “if” Indigenous knowledge is going to be shared with outsiders; instead, the question is how and under what terms the knowledge is to be shared, as asymmetrical relations between tourists and locals shape the interaction. One way to bring together different types of knowledge as equal partners is intercultural translation.

Shamanic tourism has no doubt forever changed the landscape in locales like Iquitos in Peru and Huautla in Mexico. If anything has emerged from the study of shamanic tourism in the last 25 years, it is the contradictions embedded within it. Shamanic tourism is transformational not just for the individuals participating in it but also for the local milieus where it takes place. However as some scholars have demonstrated, tourism does not necessarily destroy tradition but can in fact reinforce it. Particularly spiritual tourism can contribute to cultural transformation rather than loss, as is the case of the renewed interest in shamanism in Amazonia. However, as shamanism is transplanted and practiced in new contexts, it remains to be seen whether it will be recognizable only to the extent that it fits preconceived notions reproduced in dominant narratives.

Evgenia Fotiou (Ph.D., Anthropology, UW-Madison, 2010) is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Kent State University. She researches Indigenous religious and healing traditions in cross-cultural perspective and her research has taken her to the Peruvian Amazon since 2002. She can be reached at evgeniafotiou@gmail.com

Related Articles

Poetry and History in 18th-century Brazil

In his presentation of the beautifully published volume, Obras Completas de Alvarenga Peixoto, historian Kenneth Maxwell turns our attention to one of his specialties, the late 18th-century

Religion and Spirituality: Editor’s Letter

Religion is a topic that’s been on my ReVista theme list for a very long time. It’s constantly made its way into other issues from Fiestas to Memory and Democracy to Natural Disasters. Religion permeates Latin America…

Buscando America: A Sephardic Pre-History of Jewish Latin America

When I give public lectures about Conversos and Sephardim in the Americas, whether it is in the United States or South America, I always get at least one question, “Columbus was Jewish,