Sisters, Brothers, Young Lords

A Common Cause: 40 Years of Struggle and Remembrance

I had forgotten how young, defiant and determined we were. We saw ourselves as instruments of change, students of revolution. What we lacked in terms of experience, we made up for with enthusiasm and commitment. Viewing photographs from forty years past, we milled through the exhibit, scrutinizing photos, graying militants remembering, owning our pasts. Like many of those present at the gathering, I had carved my path to activism on city streets. Forty years later, I retraced those early steps.

On September 19, 2008 I gathered my notebooks, my memories, and a tape recorder and traveled to Chicago for a reunion of sorts, a series of events commemorating the 40th anniversary of the founding of the Young Lords Organization (YLO). A militant Puerto Rican organization in the United States, the Young Lords’ bold, innovative, mobilizations garnered the attention of surrounding communities as well as the media and local police.

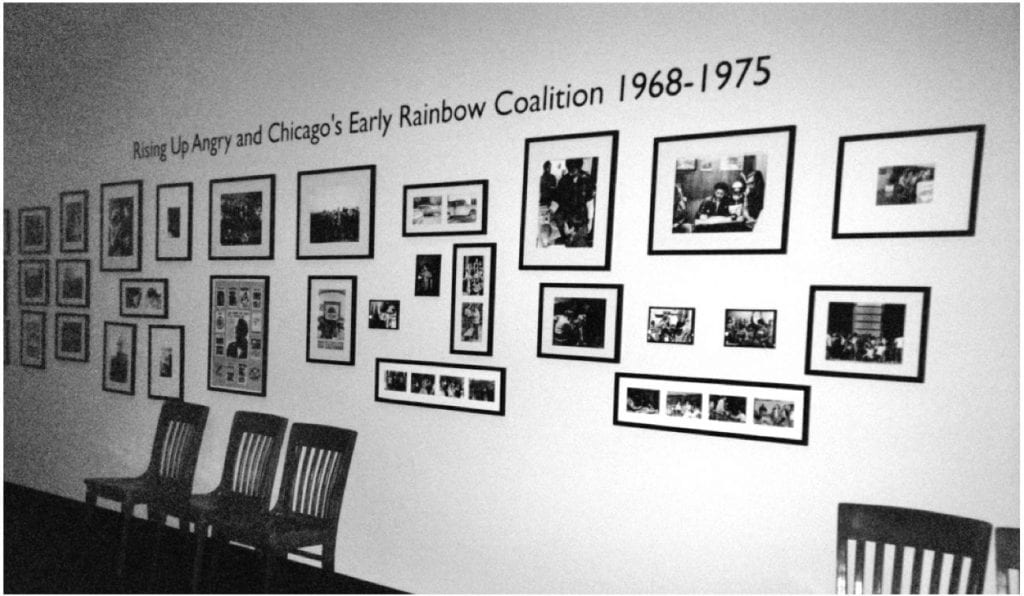

Several photographers documented the organizing efforts of the Young Lords during the late 1960s and 1970s. These images formed the core of the photo exhibit titled “Radicals in Black & Brown:! Pa’lante!, People’s Power, and Common Cause in the Black Panthers and the Young Lords Organization,” at De Paul University.

The exhibit, along with the panel discussion and community rally that followed, brought together several Young Lord and Black Panther Party members, a crowd reflecting the dreams and tensions of an era. They were joined by other community members, students, and activists from Chicago, New York, California and Puerto Rico, a blend of both old and new voices.

Among the photos of downtown demonstrations, neighborhood protests, free breakfasts, and health clinics, and close-ups of Young Lord members, portraits of whole neighborhoods emerged. These were the streets of Chicago and New York that we grew up in, where conditions drove us to organize. Embedded in these photos were the faces of children of Latin America, a connection that migration could not sever.

Those ties were clearly visible in the photograph of the Armitage Avenue Methodist Church, the site of the YLO headquarters in Chicago. In 1968, Chicana muralist Felicitas Nuñez painted a mural across the face and sides of the church, featuring iconic figures from Latin American history. Giving prominence to the image of the revolutionary Ernesto Che Guevara, Nuñez completed her vision of Latino/solidarity with other figures, among them, independence leader Ramón Emeterio Betances and the legendary Adelita of the Mexican Revolution. This mural encapsulates the internationalist perspective of the organization.

Though born of urban North America, the Young Lords embraced independence and rebel movements across Latin America. Central to their ideology, independence for Puerto Rico became a mobilizing slogan, underlining the vision that political power and self determination in urban communities coalesced with the island’s independence. Like Nuñez’ mural, YLO literature, newspaper articles, and proclamations symbolically linked arms across North America, extending into the Caribbean and Latin America. Though largely made up of Puerto Ricans, the organization with the motto “I have Puerto Rico in my heart” attracted Mexicans, Dominicans, Cubans, Panamanians, African Americans, and Colombians to its ranks. (Iris Morales, “Palante, Siempre Palante: The Young Lords,” (New York: Public Broadcasting Service, 1996), videocassette.)

Originating in Chicago, the Young Lords Organization evolved from a street gang that became politicized during the 1960s. “Cha-Cha” Jiménez, a young man who would later become the General Secretary of the Young Lords Organization, traced his development in a short biographical sketch produced by his defense committee during one of his stints in the penal system. Meeting Black Panther leader Fred Hampton and Chicano leader Corky Gonzalez were pivotal events for Jiménez and the Young Lords. However, it was his life as the child of a migrant camp worker and as a youth in Chicago barrios that planted the early seeds of activism.

Jiménez’ early years illustrate an itinerant existence that led his family from poor communities in Puerto Rico to what he called the “rat -and roach- infested apartments” of the Water Hotel of Chicago. The migratory experiences of the Jiménez family, together with settlement in poor communities and subsequent displacement from substandard housing, represented a trajectory taken by many Puerto Rican families who settled in Chicago during the 50s and 60s( See Rachel Rinaldo, “Space of Resistance: The Puerto Rican Cultural Center and Humboldt Park,” Cultural Critique, No. 50 (Winter 2002), pp. 135-174).

The Jiménez family moved, along with untold numbers of Puerto Rican families, as Chicago neighborhoods such as “La Clark” and “La Madison” became victims of urban renewal and gentrification into a Chicago neighborhood known as Lincoln Park, where a number of “European gangs” claimed particular sections as their own territory, off limits to Puerto Ricans. The subsequent organization of Puerto Rican youth into groups known as the Black Eagles, the Paragons, the Young Lords, resulted in clashes between Puerto Ricans and the “European gangs.”

While Jiménez’ life was not emblematic of all Chicago Young Lords, his political transformation and leadership position, as well as the politicization of many urban youths during that era, led to the gang’s conversion into a militant organization. Positioned against white gangs in Chicago, Jiménez’ experiences in Lincoln Park helped solidify his Puerto Rican identity, while his prison self- education, a blend of African-American and Puerto Rican political history, led Jiménez to reorganize and transform the defunct Young Lords gang into a political organization. Jiménez states in an interview that a Muslim trustee in prison began giving him “political books,” among them, the works of Martin Luther King and the militant Malcolm X, an interest that continued long after he left prison. , These books, he says, “led me to want to know about my history…to want to know Albizu and Che,” referring to Don Pedro Albizu Campos, the pro-independence leader of Puerto Rico’s Nationalist Party and the revolutionary, Che Guevara.

The Young Lords initially focused on community based organizing in response to issues such as substandard housing and the displacement of families due to gentrification and urban renewal projects. Describing urban renewal as “urban removal,” the Young Lords identified housing as an early focus for neighborhood mobilization. According to Jiménez many YLO members were high school dropouts, unskilled in traditional organizing techniques, and angered by community conditions and injustice. Juan González, a Columbia University student leader who later became a YLO leader in New York expressed similar sentiments regarding the group’s impetus for organizing, “We knew that our families did not deserve to live under these conditions.” Thus, challenging structures that generated these conditions became their common cause. The story of a woman and children, evicted from their Chicago apartment illustrates the spontaneous and often unconventional methods used by the YLO. “The woman came to us for help, so we broke into an empty apartment next to the [Armitage Avenue Methodist] Church & moved the family in… basically we didn’t have skills but we responded to needs. Sometimes people came to us, often we went to them,” remembers Jiménez.

As YLO protests and activities expanded, the organization attracted more experientially diverse members such as Omar López, a student leader and founding member of the Latin American Defense Organization (LADO) and Latin American Student Organization (OLAS), Alberto Chivira, a third year medical student who ran the Young Lords’ health clinic, and Angie Adorno, who helped organize a women’s group called Mothers and Others (MAO). Assessing the impact of women within the organization, Jiménez observes, “They did the work that made us look good in the community, [they subverted] the gang image, [and] stabilized what we were doing.”

At the height of their popularity, the Young Lords attempted to redress pressing issues facing Chicago’s Latino communities, utilizing the bold tactics for which they became known. These included housing, education, childcare and health services. The Young Lords of Chicago successfully occupied, renamed, and acquired the long term use of the Armitage Avenue Methodist Church building, where they operated various programs including free breakfast for children, a day care center, health clinic, and education program and maintained their “national headquarters.” A year later, young activists garnered national attention with their occupation of the First Spanish Methodist Church in New York. Iris Morales was among them.

Born and raised on 106th Street in Manhattan, Morales’ path to activism differed from Jimenez’. Yet, their anger and frustration with neighborhood conditions elicited a similar response. The daughter of an elevator operator and a factory worker, Morales became an organizer in high school, influenced by civil rights and black power movements. As a student in New York’s City College, Morales agitated for change. Prior to joining the YLO, Morales worked as a community organizer. When asked about the factors that led her to become an activist, Morales fervently stated, “Neighborhood conditions…I hated being poor.” Similar sentiment would fuel the expansion of the YLO to cities throughout the country.

On July 26, 1969, a group of young activists in New York announced the formation of the second chapter of the Young Lords Movement. Choosing the anniversary of the launching of the Cuban Revolution as their birth date, the YLO illustrated both their ideological perspective and their penchant to link local issues with broader movements. The YLO quickly made local headlines, drawing attention to the accumulation of garbage in the poorest neighborhoods of New York. The Young Lords quietly introduced themselves to East Harlem by sweeping neighborhood streets on Sundays. When community members joined them in this effort, the Young Lords asked the Sanitation Department to supply them with additional brooms. Two different offices of the Sanitation Department refused this request. The department’s intransigence and apparent lack of concern prompted a swift response. Discovering that the garbage they had bagged and collected during weekly clean-ups, remained on city streets, the Young Lords launched the first of several city “offensives.” On July 27, 1969, Young Lords blocked major streets with uncollected garbage. With buses and taxis unable to traverse the city, the Sanitation Department was “was forced to clean it up so that traffic would get by.” The widely publicized “garbage offensive” generated negative press for both the city’s leadership and the Sanitation Department. The latter responded with increased garbage collection in previously neglected neighborhoods. The Young Lords’ ability to recognize major community concerns and mobilize around them, generated support for the group, attracting new members as well as thousands of local supporters.

The New York chapter proved to be particularly media savvy, their bold actions catapulting serious neighborhood problems into the limelight. The near death of an African American child in Harlem from lead poisoning led the YLO to launch a multi-faceted campaign against the use of lead based paint in city dwellings, eventually obtaining stricter regulations for the use of lead paint and the establishment of a Bureau of Lead Poisoning Control.

When organizational differences resulted in a schism between the Chicago and New York branches, the latter renamed themselves the Young Lords Party (YLP). Collectively the YLO and YLP organized several chapters in New York and California, as well as chapters in New Jersey, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Milwaukee, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico, and Chicago. The membership reflected a transcultural exchange, produced by decades of cross migration between New York and Puerto Rico, a blend of recent migrants and subsequent generations born in the United States and the influx of Latin American immigrants. Born amid the milieu of the civil rights era and political insurgency in the United States, the Young Lords recognized the commonality of civil rights struggles and the black power movement, with what they termed “the liberation of Puerto Rican people and the right of self determination.”

Academics frame the Young Lords within the parameters of social and political movements of the 1960s and 70s. Some YLO members however, have a more expansive view, pointing to the ramifications of their protests. According to Jiménez, there are no “former Young Lords,” just “Old Lords” organizing in different ways. Many of the YLO members who provided social services in occupied churches, moved tenants surreptitiously into empty apartments, partnered with doctors and hospital staff to takeover Lincoln Hospital, demanding better medical care, have now stepped into different arenas, with several becoming medical doctors, lawyers, child advocates, union organizers and journalists. A few returned to gang life while others found religion. Jiménez works in a gang diversion program and is pursuing a master’s degree. Morales became an attorney and produced a documentary on the Young Lords. Both Lopez and Jiménez entered electoral politics. Vicente “Panama” Alba advocates for HIV/Aids prevention, while Felipe Luciano has entered the world of trade unions. Until her death, Angie Adorno brought members together at various gatherings. Photographers Carlos Flores and Hiram Maristany continue to visually document the history of Puerto Rican communities and of the Young Lords, just as they did 40 years ago. The space constraints of this article preclude naming many Young Lords who dedicated years to a common cause. Before leaving Chicago, I revisited the photographs displayed at DePaul. The decades old images reminded me that the issues we so vehemently fought for 40 years ago, still matter; the just society we envisioned yet to come.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: The Sixties

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American Press Association fellowship in 1977. Others—journalist Penny Lernoux and photographer Richard Cross—had also committed much of their lives to Colombia, although their untimely deaths were …

The True Impact of the Peace Corps: Returning from the Dominican Republic ’03-’05

I am an RPCV: a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer. For me the Peace Corps was an intense life experience, above anything else. As I continue to reflect on it, I am struck with the many and varied ways in which it continues to affect my life. As a PCV in the Dominican Republic from September 2003 to November 2005, I lived, worked, and learned in a small sugar cane-dependent community two hours outside of Santo Domingo…

In the Shadow of JFK: One Peace Corps Experience

I am often asked about the Peace Corps by students and recent graduates. The most frequent questions are, “why join?”, “what did you do?”, and “what has it meant for your career?” Here is my story. My earliest recollection of international curiosity was in the fourth grade when Sister Margaret Thomas described her experience as a recently returned missionary in Bangladesh. In high school, my sister Mary went to Peru on …