Social Spaces in San Juan

An outdoor traditional plaza in San Juan. Photo by Angel Amy Moreno.

My city, San Juan, is a social city. Its character and virtue are best illustrated and defined by the collective and individual memories of its people and those places where we go to spend time in idleness. It is a modern city, a metropolitan center that defies traditional paradigms, importing and assimilating diverse urban forms, reinventing them and creating unique social spaces that are the formal expressions of our traditions and patterns of social interaction.

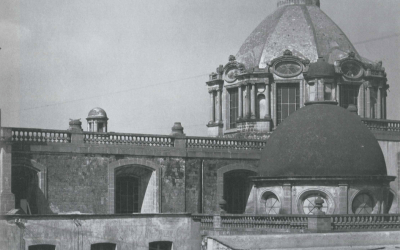

Traditionally, our urban structure, primarily influenced by Spanish planning conventions, provided the city with a distinct order characterized by the proximity between individual dwelling space and the public spaces that nurtured social interaction. The traditional Spanish plaza was truly adopted as the public living room of the colonial city, where men played dominoes and women strolled leisurely on a Sunday afternoon. The growth and development of the city has altered those patterns. This has resulted in what many have described as an overall deterioration of the traditional way of life in the city and the social fabric of its neighborhoods. In his article “Habitando entre edificios, automóviles y pantallas,” architect Javier Bonnín explains, “the separation between the city and the inhabitable private space of the house, added to the segregation and spatial compartmentalization of the rest of our daily activities, transformed and weakened the relations between individual and society.”(inForma, 2002) Indeed, these dynamics did occur in the city, particularly during the second half of the twentieth century. However, it can also be asserted that the transformation of the relations between individual and society resulted in the redefinition of the character of social space.

Social spaces in San Juan are not confined to any conventional typologies. They are not just plazas or parks, public or private in their traditional forms. They are cafés where men gather to share political stories while sipping coffee; beauty salons where women of different social stature come together to share more than just advice on hair color; or even markets that sell the freshest meats and vegetables in town during the day and host the liveliest parties at night. Our social spaces have been transformed to represent the dichotomies that characterize a sanjuanero’s life.

The center of everything

There is perhaps no better example of this transformation or redefinition of social space than Plaza las Americas, the largest shopping center or “mall” in the Island. Located in the geographic heart of the city, Plaza (as it is affectionately known in San Juan—the word plaza referring to the traditional Spanish square) has become the central square of the City of San Juan. The traditional Spanish square is overlaid with the “mall” to create a unique typology that is no longer “plaza” or “mall.” It is a new kind of space that combines the conveniences of modern city life with the peculiarities of traditional urban living in San Juan.

When I was a child, my grandmother and I would drive my grandfather to Plaza every Friday morning. I would silently wonder what he would do all day at the shopping center, knowing that he was not going shopping, as there were no bags at the end of the day. My grandfather, like many other sanjuaneros, was not from the City. Rather, he had moved to the city in search of employment and the conveniences of modern city life. Having moved to the city suburbs, he did not have a public plaza to visit, where he could share his time in idleness with friends or complete strangers. Plaza had become his plaza. Every Friday he met up with other men and sat in the central hall of the shopping center talking and playing dominoes all day, just as if they were in any other city plaza.

Plaza offered suburban dwellers the opportunity of sharing socially in a public (privately owned) space. At Plaza, they were sheltered from the harsh tropical sun and the congestion of traffic that was characteristic of other city plazas, particularly those in Old San Juan. They were encouraged to spend their days in idleness and to use the halls of the “mall” as their own public space.

Since my grandfather’s days, Plaza has changed a lot. However, it is still full of the idiosyncrasies that have made it more than just the mall, “the center of everything,” as the slogan used to promote the shopping center ideally illustrates. It is the City’s plaza, where young and old go to share, strolling leisurely through the halls and sharing meals in public tables at La Terraza (The Terrace—food court). During Christmas time you can still find groups of children and adults singing traditional parranda tunes in the halls. Artisans are welcome to exhibit their work and we still spend countless hours in idleness wandering the halls aimlessly just to take a break from the scorching heat.

The costs sanjuaneros paid for the seemingly endless expansion of the city have certainly been high. It is undoubtedly true that the carefree and convenient way of life that had been promoted by the original layout of the city has changed, leaving behind many empty plazas. In modern day San Juan, social interaction has much more to do with the car and the television than it does with the balcony and the courtyard. But this assertion cannot and should not always be equated with a degradation of social and public space. Sanjuaneros have learned to transform typologies, like the mall, to fit native tradition and create new models of social space.

My City is a city of constant social and physical change, full of places as complex and fascinating as Plaza las Americas. It is like Italo Calvino’s Zaira, a city that “does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of streets, the gratings of the windows, the banisters of the steps, the antennae of lighting rods, the poles of the flags, every segment marked in turn with scratches, indentations, scrolls.” (Invisible Cities, 1972) San Juan’s tradition is etched in the city plazas, cobblestone streets, wooden benches, and boisterous corner cafés. These places are not designed by planners or architects, they are constructed by sanjuaneros as we live and use our city.

Liz Meléndez San Miguel is originally from San Juan. As an urban designer she has had the opportunity to work on San Juan’s Land Use Plan. Currently, she is a research associate at Harvard’s Center for Urban Development Studies.

Related Articles

Bogotá: A City (Almost) Transformed

The sleek red bus zooms out of the station in northern Bogota, a futuristic symbol of an (almost) transformed city. Nearby, thousands of cyclists of all ages enjoy a sunny morning on Latin America’s largest bike-path network.

Editor’s Letter: Cityscapes

I have to confess. I fell passionately, madly, in love at first sight. I was standing on the edge of Bogotá’s National Park, breathing in the rain-washed air laden with the heavy fragrance of eucalyptus trees. I looked up towards the mountains over the red-tiled roofs. And then it happened.

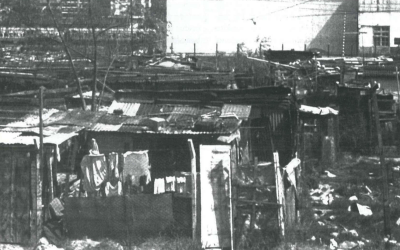

Low-Income Housing in El Salvador

El Salvador’s tremendous housing deficit had slowly begun to improve in the late 1990s. Then devastating twin earthquakes in early 2001 literally shook the country’s economic and social …