Socialism with Commercials

Consuming Advertising in Today’s Cuba

Billboard in Havana

A cacophony of sounds and colors welcomed the visitor to the annual Havana Commercial Fair at ExpoCuba on the outskirts of Havana. Displays of rum, mattresses, shampoos, cab services, travel agencies, beer, tractors, bathing suits, cigarettes, and jewelry reflected a whole world of capitalist plenty and economic optimism. Both Cuban state companies and foreign corporations exhibited their products and services.

The most popular booth at the 1998 fair, the biggest to date, was that of Cristal beer. Drawn by a gigantic sculpture of an old drunk man, and by a wall of video screens, crowds congregated to watch footage of Paulito F.G., one the most popular salsa singers in Cuba and the author of Cristal’s commercial jingle. Another audiovisual featured the history of the beer. Nostalgic images of Cristal TV ads, Havana cabarets and nightlife from the 1950s were immediately followed by contemporary street scenes of Cristal-drinking Habaneros.

The Cristal display was the main contender for the first prize of the Association of Propaganda and Advertising Professionals an association that, since 1992, has given annual awards at the Fair to the best display and promotional materials. After much debate, however, Cristal was eliminated. Why Cristal’s Canadian marketing director blamed the Communist Party, not yet ready to accept aggressive advertising. To the Association’s chief juror, a Communist Party official and advertising consultant for a competing firm who ended up getting the first prize, Cristal’s infomercial was an insult to the Revolution. It glorified the 1950s, and totally ignored the Revolutionary period. Like Wim Wenders Buena Vista Social Club, the video seemed to trace a continuity between the 1950s and present times, suggesting that economic development stagnated during what was just an interim. This juror also critiqued the use of the uninspiring figure of a drunk to attract the attention of fair attendees.

In 1997, Cristal entered into a joint venture with Labatt Beer of Canada. Canadian management and marketing expertise had an immediate impact in Cristal’s image and sales. Premium Publicity, a new Spanish-Cuban advertising agency, designed an advertising campaign. Together they devised one of the most successful and bold advertising campaigns since commercial advertisements were first allowed in 1994. They carefully packaged the beer as the drink of the new generation, and enlisted teen-idol Paulito to tour the island with a stage wrapped in Cristal logos. Radio commercials were played ten times a day, and posters of Cristal were prominently displayed in stores and bars. Cristal sales sky-rocketed. The Communist Party was confronted with a dilemma; the reintroduction of advertising was plagued with hesitation, reflecting the latent conflicts between socialist morality and financial needs. The Communist Party Central Committee cancelled Paulito’s tour after only two concerts, despite the fact that local officials in the provinces were extremely eager to have a big star performing in their sleepy towns. Party leaders saw these trends as moves that could subvert socialist consumption ethic and aesthetics.

In the early 1990s after the collapse of most of Cuba’s socialist trading partners, Cuba entered a deep economic slump. Economic reforms, designed to increase foreign currency reserves, included expansion of the tourist industry, pursuit of foreign investment, the legalization of limited forms of private enterprise, and free circulation of the U.S. dollar. The reintroduction of commercial advertisements followed as a way to attract hard currency from newly-arriving foreign companies eager to promote themselves. One radio station was revamped with a commercial format, and advertising was introduced in January, 1994 under the direct supervision of the Department of Ideology of the Cuban Communist Party.

The “drunk” that caused the controversy

To the surprise of Habaneros, the new commercial-like Radio Taino, FM, was the soundtrack of the worst economic crisis of post-revolutionary Cuba. 1994 was a year of hunger, of the balsero crisis, when tens of thousands of people fled on rafts to the United States, and a year of long electricity blackouts and severe gas and water shortages. The first commercials appeared during the same time, suggesting instead the possibility of capitalist consumption and a world characterized by leisure and abundance rather than labor and shortages.

However, some unintended consequences quickly appeared. For example, the campaign of the Spanish beer San Miguel was so successful that it became the beer of choice in the city, nearly driving local beers out of the market. Shortly after that a beauty product campaign generated complaints from offended listeners who questioned the government for promoting such products while failing to provide enough running water to the majority of the population and for discontinuing the distribution of soap through the rationing system.

The government, beginning to understand the power of advertising, issued regulations. It realized that advertising revenues should be higher than the losses that state companies endured as a result of foreign competition. As a result, Radio Taino raised its advertising fees by 700 per cent. Multiple and recorded spots replaced individual sponsorship to avoid over-promotion of any one company or brand. Meanwhile, Cuban state companies were given the opportunity to advertise for free or at very low rates in order to boost their sales and survive foreign competition. Along these lines, the promotion of foreign firms was substituted by that of their state-run Cuban subsidiaries. Advertising of independent entrepreneurs was banned outright. So was the advertising of basic products, as well as the promotion of certain luxury items that reflected the population’s increasing economic disparities. Finally, Radio Taino advertising designers were instructed that ads should be informative but not lure people to consumption; they could contain persuasive slogans with informative statements. At this point it became apparent that advertising was a highly visible aspect of new economic relations at work.

The Communist Party’s Department of Ideology has issued internal advertising regulations periodically to all ministries and state institutions since 1993, revealing the philosophical confrontation between political and commercial propaganda under socialism. 1998 regulations establish that the Communist Party will monitor advertising, which must always comply “with the moral and political principles of the Revolution.” Advertising should neither “subvert socialist ideology nor the cultural identity of the Cuban nation” nor utilize national symbols or public government figures. Advertising should not harm the country’s economic interests in any way and should not “appeal to the consumption of products and services,” although it can disseminate and promote company and brand names. Promotion toward commercial ends at least for the time being will be limited to billboards with locations approved by the Communist Party, audiovisual media and printed material directed at foreign nationals (including Radio Taino), and the interior of businesses that sell products in hard currency.

Radio Taino is currently the only electronic mass media on the island to include commercials, although state television is currently considering their introduction. Newspapers, however, use advertising to survive. The Communist Party paper, Granma, includes printed ads in its international version, and the Union of Communist Youth edits a business paper, Opciones, whose ads help to subsidize its official newspaper, Juventud Rebelde. Increasingly, international events such as the Havana Latin American Film Festival and the International Jazz Festival rely on sponsorships and advertising for funds.

Advertising, initially intended as a mere income-generating strategy, has unleashed an unexpected, wider cultural transformation. For instance, the media is no longer simply an instrument of socialist ideological education, but also of marketing products, services, and popular culture a realm characteristic of capitalist socialization. Programming at Radio Taino is now designed with the goal of attracting an audience, which becomes a commodity to be sold to advertisers. Research centers associated with the socialist economy, like the National Center for Statistical Research, and the Institute for the Study of Domestic Demand closed their doors a few years ago as their goals were deemed obsolete. Their researchers have been recycled to conduct audience and market research, applying new techniques to identify a market segmented along consumption patterns, income and professional lines. Socialist institutions in charge of promoting new products have been reconverted into marketing and public relations consultants. The 1999 Cuban National Directory of the Communications Industry lists nineteen advertising agencies, although only four manage standard advertising accounts and design entire campaigns. An Association of Propaganda and Advertising Professionals, formed in 1991, now has more than 1,500 members.

1994 San Miguel billboard

This association seeks to include all professionals in the communications field who are not journalists. Its founding members, now on the association’s executive committee, were mainly Communist Party members with long experience in propaganda. Most of them had also been in the field of commercial advertising prior to the Revolution as account executives, graphic designers, photographers, writers and draftsmen. As the mass media and all private enterprises were nationalized by 1962, most advertising professionals left the country in search of better employment prospects. With the exception of the promotion of specific export products abroad, commercial advertising slowly dwindled and disappeared. Those professionals who stayed in Cuba either worked on international advertising or, for the most part, have worked over the years designing both political propaganda and public education campaigns. The 1961 Literacy Campaign, for instance, was conceived by former advertising executives and led, of all people, by the juror that vetoed the 1998 award to Cristal (a former accounts manager with McCann- Erickson and later a close collaborator to Ernesto Che Guevara at the Ministry of Industry). In the late 1980s, these professionals began to call for the rehabilitation of marketing and its use to increase economic efficiency and introduce new managerial styles at Cuban state companies. Today, the expertise accumulated in political/ideological campaigns is being transferred to the design and production of commercial advertisements, as in the early 1960s when the exact opposite process took place.

Cultural studies theorists have linked the rise of advertising in American culture with the development of new economic relations as it occurred at the end of the 19th century.

Then as now, advertising highlights the importance of consumption in the creation of wealth and becomes a symbol of new economic relationships with a new approach to both labor and leisure. Individual worth is no longer linked to his or her position in the production process, but is increasingly defined in terms of consumption habits, in turn associated with leisure patterns. Advertising also is one aspect and one of the most visible ones — of the principles of marketing and economic efficiency linked to capitalist economic relations. It has also opened new employment opportunities for artists, writers, photographers and others who, according to new laws regulating self-employment can freelance without being linked to a state enterprise. The advertising field thus presents one of the most important changes in Cuban labor relations. Salaried employees at advertising agencies often leave their jobs to become “independent creative workers” and work on a free-lance basis. Since advertising takes place in the hard currency economy, these professionals value their work in hard currency. They exchange the security of a fixed salary of about 20 to 40 dollars a month for the uncertainty of contract work. However, because there is still little competition in the field, agencies have no choice other than to contract them at international market fees, making their earnings comparable in many cases to those of their peers in other parts of Latin America.

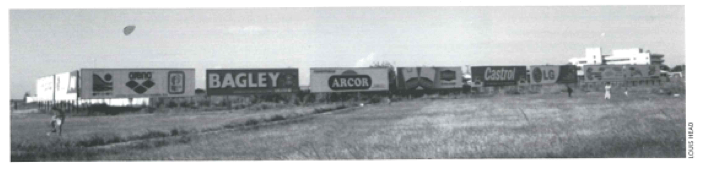

Billboards in Havana’s Miramar neighborhood

In today’s Cuba, beyond billboard ads and corporate sponsorships, beyond the highly visible economic reforms, there is a tremendous cultural transformation that affects not only the audiences that advertising seeks to reach, but also those involved in its design, production and mass media dissemination.

Winter 2000

Ariana Hernández-Reguant is a PhD candidate in Cultural Anthropology at the University of Chicago and a teaching fellow at Harvard University’s History Department. She is currently writing her dissertation on “The Culture Industries between Communism and Capitalism in Contemporary Cuba.

Related Articles

Isabelle DeSisto: Student Perspective

encountered the first obstacle of my trip to the Isla de la Juventud before I even left Havana. Since American credit cards don’t work in Cuba, I couldn’t buy my plane tickets online. But that…

Honoring Humanity: An “Interview” with Richard Mora

Mauricio Barragán Barajas: Why don’t we begin by having you introduce yourself? RM: Alright. I was born in East Los Angeles, and grew up in Cypress Park, a barrio in…

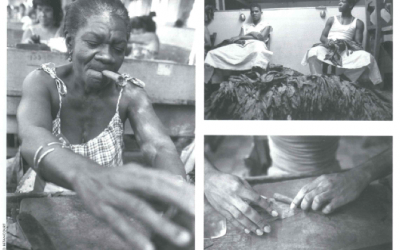

Tobacco and Sugar

“Tobacco and Sugar” is the course that focuses American literatures on the Caribbean, and that acknowledges the unavoidable importance of monocultures for cultural studies. Much of the…