Monumental Callao is a Step Forward for Peru’s Most Crime-Ridden Area

The reclaimed space has transformed the surrounding blocks into a haven for street art and budding professional artists. The displayed works are impressive, but the most immersive and noteworthy pieces are found outside the galleries.

Monumental’s hallway and many small galleries. Photo courtesy of Manuel Sanchez-Palacios.

The taxi ride to Monumental Callao is a gallery visit in itself. Murals, graffiti, 19th-century pastel-colored houses and street carts called ambulantes sell fruits, various fried concoctions and even ceviche in a plastic bag. It’s a colorful reminder that often, underprivileged areas are the most culturally rich. However, after exploring Monumental the budding gallery is tame in comparison to the artistry in the streets. Only a handful of exhibits represent how this transformed space could have accentuated what was outside.

A long hallway stretches down the restored ‘Ronald’ building. Above, a stained glass ceiling illuminates the exhibits, which displays a variety of art. There are two restaurants and two art and clothing stores. It’s a stark contrast in comparison to the surrounding area.

Monumental Callao is located in Peru’s most dangerous neighborhood. The name Callao is often associated with crime, and poverty. The gallery is a social initiative that promotes a commitment to improving the area’s future through art. As noted on Monumental’s website, in the reclaimed public spaces, crime dropped 90%.

The majority of the building is reserved for resident artists’ studios, but filling the lower levels are small spaces with a number of eclectic art styles and some photography.

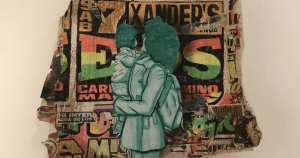

Impressive works were displayed that enlighten audiences to Lima and Callao’s culture. An exhibit titled Entes used a unique fiberglassing technique to strip the plaster from the graffitied and poster-filled walls of Callao to present a physical ‘screenshot’ of what the streets actually look like. It was the only room that brought the outside ‘in’ through this technique. Unfortunately, the size of the room limited its potential.

Entes, a piece that stripped posters and graffiti from streets. Photo courtesy of Manuel Sanchez-Palacios

Entes, a piece that stripped posters and graffiti from streets. Photo courtesy of Manuel Sanchez-Palacios

An exhibit by Aarón López called Por Encargo makes an attention-grabbing statement. Upon entering, a startling statistic introduces the pieces, “Homicides in Callao are responsible for 7.2% of the total deaths in Peru.” This particular exhibit gave a better understanding of the surrounding areas’ present need for safe expressive sites. Leaving the exhibit, a painting with two bullets rendered to look like tubes of lipstick reminds you of violences’ omnipresence in Callao. It might also be a nod to high rates of femicide in Peru that have recently surged throughout the pandemic.

The modernist and abstract exhibits inside felt uninspired. It seemed like the gallery included these pieces to fill a pigeonhole that European modern art galleries lacking any Rothko or Pollack might use. Next to these was an exhibit with poetry containing pragmatic observations printed in the largest font possible. It was also underwhelming.

In comparison, the most unsettling exhibit in Monumental was one by Maria Abbadon titled Carne Viva, or Live Meat. Stockings stuffed with dyed and spray painted cotton balls are strewn across the floor made to look like a gigantic amalgamation of entrails. It is a vague piece. Understanding whether it was an ode to the abstract or a statement in regards to violence was unclear. The description garnered no clarification since it said, “In celebration of meat.”

The most moving art was not, in fact, within the gallery, but rather outside. In the street, you can buy a bag of yuqitas—balls of fried dough— before wandering to see the more poignant murals and graffiti. After this experience, It’s clear what was lacking from most of Monumental’s interior exhibits: authenticity.

A view of the outside from a window in Monumental. The mural says, “Think and act, wandering soul, always fly high – ‘Callao, Peru’” Photo courtesy of Manuel Sanchez-Palacios.

A view of the outside from a window in Monumental. The mural says, “Think and act, wandering soul, always fly high – ‘Callao, Peru’” Photo courtesy of Manuel Sanchez-Palacios.

The oversized murals in the streets were the most impressive. Exiting the Costa Verde expressway into Callao, you are greeted by a dilapidated building, burnt from a recent fire. On the largest surviving facade is an impressionist stylized face that could situate itself in Picasso’s Guernica. Written below the portrait it says, “Callao 2021.” Graffitied Ventanilla ‘Q3’ Cartel also peppered many walls of houses. Murals of residents, musicians and vendedores also appeared along the way.

A few blocks away from Monumental was a profound reminder of Callao’s infamy.

A wall says, “Siempre con nosotros, guardianes del barrio,” which translates to “Always with us, the guardian of the neighborhood,” with two young boys in referee jerseys covering the street-facing façade of a bodega.

The streets surrounding Monumental’s galleries are raw. They constitute, physically and integrally, the art and culture of the place.

The views of the outside from the upper levels of Monumental offered glimpses to more street art. You feel a greater appreciation of the art in Callao, ironically, while looking out of the place meant to house the majority of it.

The street art is framed between windows near Monumental. Photo Courtesy of Manuel Sanchez-Palacios

Monumental’s exploits are worthy by offering a beacon for those seeking a safe expressive space for the public and artists. The gallery gives a home to those who desire a certain escapism through art. However, it largely ignores where the best art and artists are, in the streets.

A redeeming factor might’ve been the street-walking tour offered at the entrance to the free exhibits, but the extra cost and tardy guides were dissuading. Overall, what was already there in the streets made the exhibits fall flat. A few pieces were impressive, although Monumental has some curating to do. If it were to reach its full potential, it could be a cathartic experience healing Callao’s violent past.

On the way to Monumental, the brief moments where the taxi slowed at stoplights and in traffic gave an opportunity to glance at the street art. I recommend visiting Monumental, but here the adage “it’s about the journey, not the destination” holds true.

Fall 1999

Manuel Sanchez-Palacios was born in the United States to his two Peruvian parents. He moved to Lima In January of 2020 after graduating from UC Santa Barbara and began studying for a Master’s in Liberal Arts with an emphasis in Journalism through Harvard Extension. His favorite hobbies are writing, surfing, drinking coffee, and playing the guitar.

Related Articles

What Your Naked Bodies Told Me

Twelve actors were seated on a game board, staring intently at us. I entered and took a seat in a chair in the corner. Spectators were scattered across the board, clustered in small groups of five or six around each actor. In front of me on the floor sat actor Daniel Tonsig, who looked deep into our eyes for long, silent seconds.

De aquí y de allá: A View of Los Angeles in San Antonio

You never know what to expect from a Frank Romero exhibit.

A ReView of La Misma Luna

With teary eyes, I finish watching Patricia Riggin’s 2007 film La Misma Luna one more time, a testimony of the unconditional love between a mother and son. Carlitos Reyes, a 9-year-old boy, who lives in Mexico with his grandmother.