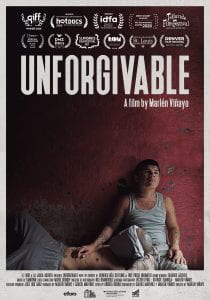

A Review of Unforgivable

This documentary directed by Marlén Viñayo navigates the complicated relationship between machismo, violence, belonging and homosexuality from within a Salvadoran prison.

They are some of the most dangerous men in the world.

Racketeers. Torturers. Murderers.

All of them belong to rival “maras,” or gangs, which originated in the streets of California in the 1990s and grew to become a transnational criminal phenomenon with over 69,000 members scattered throughout El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras.

Often, “mareros” are portrayed as a deadly fleet of heavily-tattooed men that commit some of the region’s most heinous crimes. But “Unforgivable” takes the audience in a completely different direction. The powerfully evocative documentary, directed by Marlén Viñayo and produced by news site El Faro, tells the compelling story of two men, Geovanny and Steven who fall in love behind bars despite being members of rival gangs, 18th Street and Mara Salvatrucha.

The end result is a work that is raw, unfiltered and emotive. The narrative arc is tragic and unresolved; a bold attempt to show the inherent complexity of mareros, one of the most hated and misunderstood groups of Salvadoran society with aplomb.

“I fell in love with him and I would ask myself why this is happening if I am a gang member,” Geovanny confesses to the omniscient camera from his cell in the San Gotera prison in western El Salvador, where the 35-minute documentary short takes place.

At first, the film depicts Geovanny as an unsympathetic character who became a cold-blooded killer after joining the 18th Street gang at age 12. In a shocking scene within the film’s first few minutes, he tells the morbid account of ripping out a victim’s heart and eating it.

It is only later that it is revealed that he had been brutally raped and assaulted as a young child by an older man. He found solace and belonging when he joined his “mara,” which is also a slang term used in Central America for “my people.”

“I had all this anger in me,” Geovanny says in the film. “Why was I fighting? I still don’t know.”

One of the most impressive aspects of the documentary is the unprecedented access Viñayo had of the maximum-security prison. The director takes the audience through the exposed hallways, the brick-and-mortar walls and the dead tropical heat inside the one prison wing reserved for gay gang members.

It is there that the camera communes with Geovanny, Steven and others in a six-foot-squared space to show everyday life: Geovanny sewing pants out of a white fabric, Steven making hot cereal and the two of them laughing, hugging and crying.

What transpires is an intimate portrayal of three simultaneous relationships; to each other, to gay gang members and to the prison’s politics—where a majority of the inmates have converted to evangelical Christianity and believe, as the prison’s pastor says, it is “better and easier for God to forgive a gangbanger than a homosexual.”

Identifying as a member of the LGBT community is a death sentence in the Central American nation home to five million people. Human Rights reports say Salvadoran gangs have targeted LGBT people for violence or threats of violence specifically because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

Instead of painting the painful issue in a larger context, Viñayo does the opposite; closes the aperture of the camera zooming in on one couple, in a confined space, deprived of their liberty—and maybe even their lives—all because of their love.

It’s an effective directorial choice that serves to elucidate how El Salvador has remained among the top five bloodiest countries in subsequent years and among the most dangerous for LGBT people.

It is something Geovanny and Steven know all-too acutely. The pair met five years before cameras started rolling and say it was love at first sight. After locking eyes, they scurried off to be alone and away from the gaze of gang leaders. They kissed.

Should they be discovered and be killed, Steven told Geovanny in a gut-wrenching scene, “let it be in the name of love.”

Eventually the never-ending sense of danger becomes untenable for Geovanny, forcing him to request being transferred out of that prison to one that is less dangerous for gay inmates.

To do this, Geovanny must jump through bureaucratic hurdles, psychological evaluations and out himself to the penitentiary system—and his family. But in the process, he must leave Steven behind, who is conflicted by his own sexuality and Christian beliefs and refuses to tell his family.

Ultimately, the men must choose between faith and love.

It is at that moment when the audience is utterly crushed. The effective documentary has succeeded: we see Geovany and Steven for more than tattoos, violence and poverty.

The film also has a strong journalistic element, anchored by Salvadoran journalist Carlos Martinez from El Faro who worked with Viñayo to interview the men, frame the conversation and offer three decades of history and reporting to bring the story to light.

Perhaps the biggest tragedy of all is that we are left with more questions than one short film can answer about a complex country.

As Martinez told Spanish newspaper “El País,” “How does a 12 year old become a killer? How could they have sexually abused a child? How could he have committed such crimes?”

We wonder what role, if any, does love play in redemption.

Romina Ruiz-Goiriena is an ALM candidate at Harvard Extension School in the field of journalism and a national correspondent for USA TODAY. Previously, she reported out of Central America for CNN and The Associated Press, covering issues such as migration, corruption and drug trafficking. She has also worked in Paris, Cuba, and Israel for France 24, El Mundo and Haaretz. Romina is fluent in English, Spanish, French and Hebrew.

Related Articles

What Your Naked Bodies Told Me

Twelve actors were seated on a game board, staring intently at us. I entered and took a seat in a chair in the corner. Spectators were scattered across the board, clustered in small groups of five or six around each actor. In front of me on the floor sat actor Daniel Tonsig, who looked deep into our eyes for long, silent seconds.

De aquí y de allá: A View of Los Angeles in San Antonio

You never know what to expect from a Frank Romero exhibit.

A ReView of La Misma Luna

With teary eyes, I finish watching Patricia Riggin’s 2007 film La Misma Luna one more time, a testimony of the unconditional love between a mother and son. Carlitos Reyes, a 9-year-old boy, who lives in Mexico with his grandmother.