The Caribbean Spirit

Preserving Our Heritage and Ancestral Rights

Our community and other Afro-descendant tribal communities on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast are confronting what seems to be a systematic attempt by the state to uproot our community. For decades, Costa Rica has refused to grant property titles and infringed on our rights to property by targeting ownership over our ancestral lands, even to the extent of issuing demolition orders.

We are resisting. Our story of resilience begins in Nigeria, Gambia, Equatorial and Western regions in Africa, extending to the shores of the Caribbean Sea. In the lush tropical rainforest of Costa Rica, between the symphony of cicada singing and the dance of the jungle canopy, we have been autonomous on the shores of the Caribbean Sea for centuries. A past of struggle wove the tapestry of the rainforest and sea, giving rise to our deep connection with our ancestral lands.

I was born and raised in Old Harbor, where leaves whisper, waves tell tales, and the spirits of our Igbo ancestors softly speak. As a bearer of our collective memory of the Afro-Caribbean legacy, I share this rich narrative with my son, Omi, age six. Hand in hand, we tread the very shores our ancestors once walked, guided by stars, the Caribbean sea and stories, along the historical beach path that our people journeyed by foot and by horse, connecting the vibrant tapestry of the Creole communities of the coast in Central America.

“Omi,” I say, as we gaze across the vast sea, “your name means ‘water’ in Yoruba; this symbolizes the journey of our ancestors from Africa to the West Indies to these shores. It reflects our strength, our resilience.” As a mother and his first educator, I weave our oral history into our daily lives, ensuring that the legacy of our ancestors, their struggles and triumphs, are etched in his heart, for he, too, must live in this skin.

My great-grandfather, William Brown Duff, was a son of the Caribbean. Only one generation separated him from the shackles of enslavement; in his memories lived the terror his grandparents shared of their travails on their voyage to Jamaica from Nigeria and the subhuman fate they met there. William, just 12 years old at the time, embarked from Jamaica in search of a better life. He worked as a water carrier in constructing the Panama Canal, traveled through Nicaragua, and finally, in 1918, settled in Costa Rica with my great-grandmother, Viola Smith, belonging to the founding family of Cahuita. William entered this tropical coastal world unaware of the challenges this new environment would present: malaria, endemic to the rainforest, and the hostile climate constantly testing the resolve of its inhabitants, thus, the resilience and indomitable spirit of our Black community.

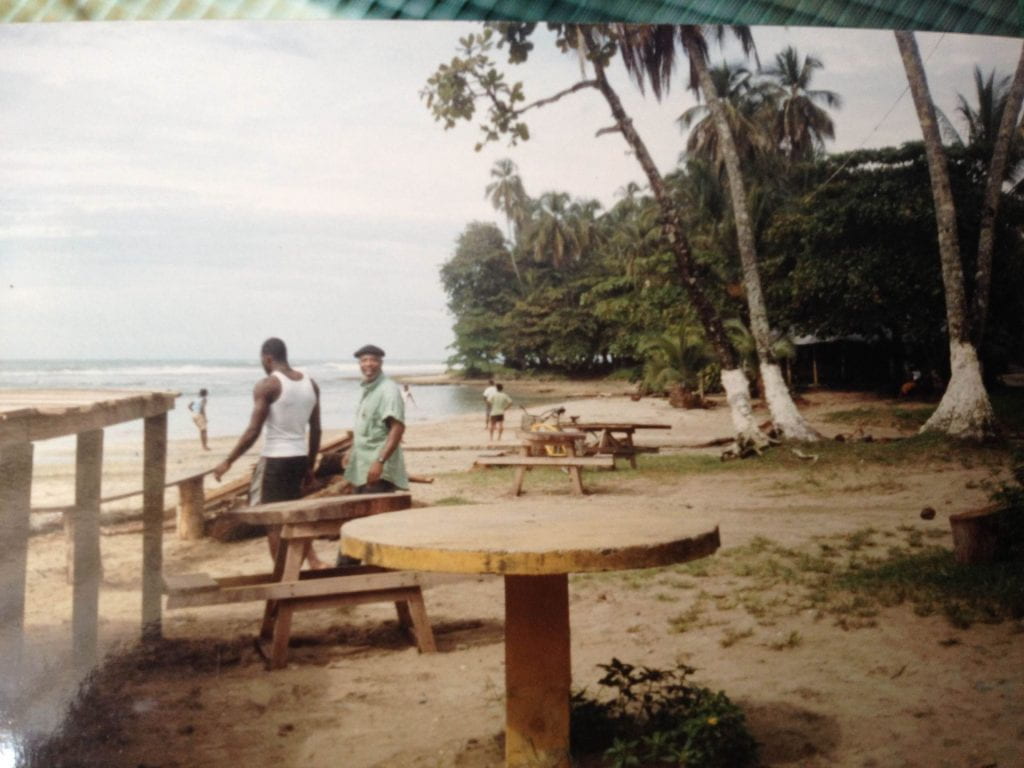

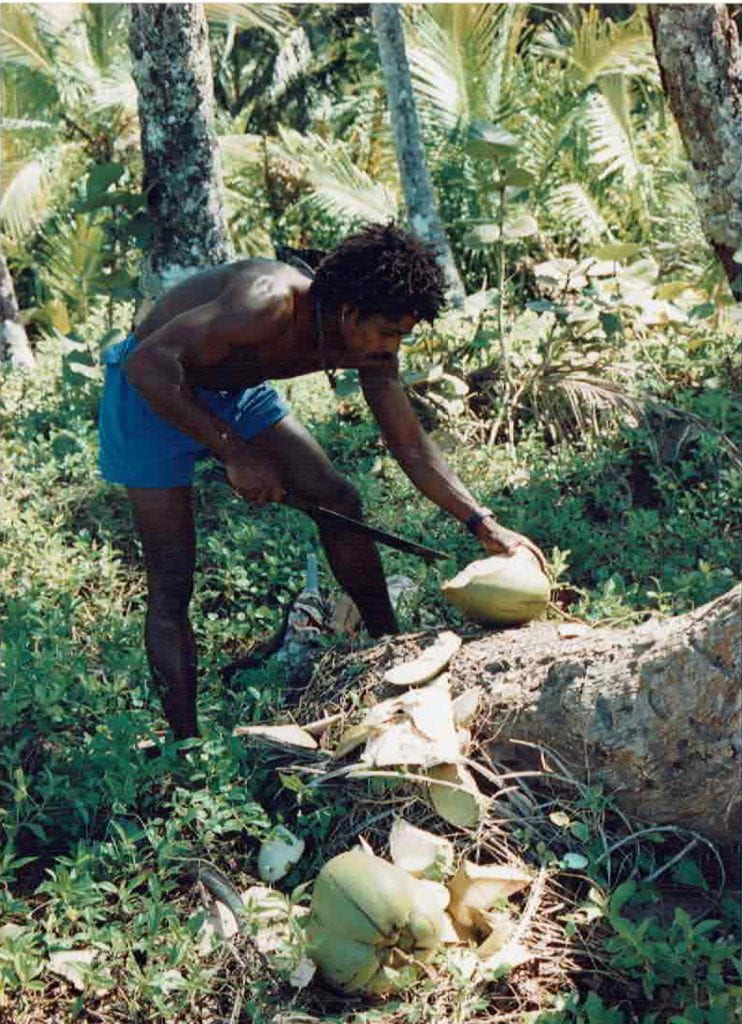

Our ancestors, the Bryants, Hudsons, Smiths, and many more of the founding families of Cahuita’s district, forged the towns of the southern Caribbean of Costa Rica with their work-rough hands and unbreakable spirits. As Omi and I tread the sandy shores, our steps lead us to the fertile grounds of Mr. Edgar Campbell’s farm. The air is filled with the rich scent of earth and growing herbs, spices, fruit trees and medicinal plants “Bush Medicine”, the land’s abundant vitality. Mr. Campbell, a man whose smile beams like the morning sun as he spots us. “Ah, visitors! Welcome, welcome!” He greets us warmly. We venture through his land to pick coconuts to quench our thirst, with a stride that spoke of deep familiarity and reverence for the land, guiding us through his farm, an expanse of rich soil and crops, a living narrative of resilience and heritage.

As we walked, the tranquility of the surroundings provided the perfect backdrop for Edgar to unfold the stories of why we created Afro cooperatives as agricultural ventures of cultural and environmental preservation. “The creation of Coopecacao Afro, as many more afro organizations and initiatives” Edgar began, his voice carrying the weight of the story he was about to tell, “was primarily a means to protect our land rights.”

He shared with us how, in the district of Cahuita, the land is more than a physical asset; it’s the soul of the community, entwined with centuries of history, culture, and ancestral wisdom. The cooperative emerged from a dire need to shield this heritage from the encroachments of external interests and to assert the community’s sovereignty over these ancestral lands. Edgar and fellow members in our community embarked on a journey to sustainably manage resources, leveraging agroecological practices that honor the earth and its cycles.

As we paused by a patch of cacao trees, Edgar plucked a ripe pod from the branches, splitting it open to reveal the rich, fresh beans inside. “These,” he said, gesturing towards the beans, “are more than the source of chocolate, they’re a symbol of our identity, of our struggle and resilience. By producing our chocolate, we’re creating a product; we’re reclaiming our heritage and ensuring the survival of our traditions for generations to come.”

Omi listened intently, his young eyes wide with the unfolding realization of the land’s deep stories. Edgar’s narrative is an account of agricultural practice and a lesson in stewardship, resistance, and the profound bond between people and their land.

As we continued our walk, the conversation shifted to the future—how Coopecacao Afro was cultivating opportunities for the youth, ensuring that children like Omi would grow up empowered by the knowledge of their land and the strength of their roots. Edgar’s vision was clear: a community self-sufficient and resilient, bound by the shared goal of preserving the cultural and environmental legacy.

Our journey through Edgar Campbell’s farm was a passage through the layers of history, struggle, and hope.. Edgar turned to Omi, his gaze both stern and warm. “Remember, young man,” he began, his voice firm yet imbued with an almost paternal kindness, “a Black man’s farm is his pantry.”

He paused, allowing the weight of his words to sink in, then continued, “It’s crucial for us to rely on ourselves, to nurture our community and our families with what the earth gifts us.” With a gesture that encompassed the expanse of his farm, he shared the essence of his wisdom, “Here, we grow more than just food; we cultivate life. From the crops that feed us to the medicinal herbs that heal us, like the ‘BUSH TEA’ make sure you drink ‘bear bush,’ every part of this land sustains us.” Edgar’s farewell to us included a quote by Marcus Mosaih Garvey, reminding us that “a people without knowledge of their past history, origin, and culture is like a tree without roots.”As we left the farm, the setting sun casting golden light over the fields, I could see a new understanding reflected in Omi’s gaze. It was a recognition of the importance of roots, of land, and of the stories that bind us to both.

The Unseen Battle of Costa Rica’s Afro-Descendant Communities

In Costa Rica, a nation renowned for its dedication to peace and environmental conservation, lies a less visible narrative that contrasts sharply with its idyllic image. This narrative belongs to us, the Afro-descendant communities of the Caribbean coast, who find ourselves trapped in a struggle against laws that threaten our very existence on our ancestral grounds. Despite Costa Rica’s international acclaim for its lush rainforests and commitment to ecological preservation, our story reveals a different reality—one in which the principles of environmentalism justify the displacement of Afro-communities with deep-rooted historical and cultural ties to these lands.

The challenges of race and racism in Latin America and the Caribbean are complex and pervasive, and Costa Rica is no exception. Our territories—the lands our ancestors have nurtured, cultivated, in great harmony with nature and called home for generations—are under siege. This reality transcends national borders, languages and histories, uniting us with other Afro-descendant populations in a shared struggle for recognition and rights. Costa Rica’s approach to managing its environmental resources under the guise of conservation has led to the systematic uprooting of our communities. This sophisticated masquerade of ecological stewardship, which has garnered international praise, masks a bitter truth: the displacement of people under the pretext of protecting nature.

The irony of this situation is profound. As Costa Rica receives accolades for its environmental initiatives, the lands and traditions of Afro-Caribbean communities are quietly being eroded. Our rights, histories and very identities are swept away in the so-called tide of progress, leaving us to contend with the ramifications of policies that fail to acknowledge our existence and contributions to the cultural and ecological fabric of the nation. This scenario underscores the challenges and achievements concerning race and racism in Costa Rica, revealing a nation grappling with deep-seated issues of racial displacement and discrimination, all under the veneer of environmentalism.

A Legacy Overlooked and Under Threat

The Constitution of Costa Rica, with its amendments emphasizing a multiethnic and pluricultural society, promises equality, property rights and environmental protection. These legal frameworks were intended to herald a new era, recognizing the diverse tapestry of cultures that constitute the nation. However, the reality for Afro-descendant communities, particularly in regions like Limon, sharply contrasts with these constitutional promises. Despite legal recognition, we continue to navigate a landscape marred by systemic discrimination, exclusion and the looming threat of displacement—a stark reminder of the chasm between legal ideals and their implementation.

Nearly a decade since these constitutional amendments, the Afro-descendant communities of Costa Rica remain embroiled in a struggle for recognition, battling systemic barriers that hinder our access to justice, education and equitable treatment. The caribbean of Limon province has become a battleground for our rights.The principle of non-retroactivity, meant to protect acquired rights, and the promises of equality before the law seem to dissolve when faced with the realities of the district of Cahuita and other Afro-descendant settlements, our ancestral lands, are now under threat. They are classified under laws that render our claims and existence void. While noble in their intentions, environmental regulations and conservation efforts have been applied in ways that disproportionately affect our communities in negative ways. The creation of the Institute of Land and Colonization in 1961, an entity that enacted a massive program of land titling in the name of the state, disregarded the ancestral rights of our people, including public and private family cemeteries. The state has claimed ownership over our lands and even our ancestors’ remains, a move that ironically coincided with the time in which Blacks were given the right to vote and participate in government.

The Struggle Against “Ley sobre la Zona Marítimo Terrestre” 6043

The Maritime Zone Law (Law No. 6043) is a critical focal point because the legislation governing the coastal maritime zone threatens to displace our ancestral communities of African Descent. The law ostensibly aims to protect and manage the coast for the public good, emphasizing conservation and responsible development. However, the reality for our Afro-descendant communities, whose lives and livelihoods are intrinsically tied to these lands, tells a story of displacement and disenfranchisement, glossed over by the law’s environmental objectives.

Our ancestors, who have historically cultivated this land and relied on the sea for sustenance, find themselves at odds with a law that does not recognize their existence. The law declares the coastal maritime zone as inalienable and imprescriptible, effectively stripping us of any claim to these lands, regardless of how long we have inhabited them. It mandates that beachfront areas within the first 50 meters (164 feet) from the high tide line are designated as public space and the subsequent 150 meters (492 feet) as restricted are under state control, ousting the historical communities that have existed much before these laws.

Our practices of fishing, coconut cultivation and the utilization of bush remedies—traditions passed down through generations—are now under threat. The oversight responsibilities vested in the Costa Rican Tourism Institute and the direct compliance mandates for municipalities further complicate our struggle. While the law outlines a comprehensive framework for protecting and managing the coastal zones, it starkly fails to incorporate the rights and voices of the Afro-descendant communities. Our ancestral homes and businesses are marked for demolition, labeled as obstructions to the state’s environmental and developmental visions.

This legal situation is exacerbated by natural disasters, such as the earthquake that led to soil liquefaction in Limón province, further destabilizing our communities and bringing the coastline closer to our homes. The rise in the Costa Rican coastline by up to 6.2 feet facilitated the state’s justification for demolishing our homes and uprooting our communities, citing the need to reclaim the expanded maritime zone.

This law and its implementation embodies the broader challenges we face in securing our rights and preserving our heritage. Our fight against this legislation is not a stand against conservation, for we have always lived harmoniously with nature, but a call for a more inclusive, equitable approach that recognizes and respects the rights of all communities, especially those of African descent, who have been stewards of these lands long before their current designation as protected areas.

The “Ley sobre la Zona Marítimo Terrestre” represents a critical juncture in our ongoing struggle for recognition, justice and the right to live in harmony with the lands our ancestors have cultivated for centuries. It underscores the need for dialogue, for laws that protect the environment and uphold the rights and traditions of the communities that have coexisted with these natural spaces. Our plea is for a reevaluation of this legislation, for policies that acknowledge our historical presence, and for a future where our children can continue to thrive on the lands of their forebears, free from the threat of displacement and erasure.

Conservation’s Irony and the Impact on Afro-descendant Communities

The creation of Tortuguero National Park in the 1970s marked the beginning of a conservation era that, while crucial for the global fight against environmental degradation, inadvertently set the stage for the systematic displacement of our people. Nestled in the lush province of Limón, this park, a haven for biodiversity, became one of the first battlegrounds where the complex relationship between conservation objectives and community rights unfolded. The creation of the park and subsequent protected areas like the Barra del Colorado Wildlife Refuge not only highlighted the nation’s commitment to environmental preservation but also underscored a glaring oversight: the failure to adequately consider the impact of these initiatives on the Afro-descendant populations.

The expansion of conservation areas throughout the 1970s and 1990s, including the establishment of the Gandoca-Manzanillo Wildlife Refuge and the designation of Cahuita National Park, further complicated the lives of those within their boundaries. Our ancestral ties to these lands, predating the establishment of protected areas, were seemingly disregarded in favor of a broader conservation narrative. This dissonance between the goals of environmental preservation and the rights of indigenous and Afro-descendant communities to their ancestral lands highlights a critical gap in the conservation discourse. This gap overlooks the human dimension of environmental stewardship.

The conservation story in Costa Rica, particularly in the context of Afro-descendant communities, is a poignant reminder of the need for a more inclusive approach to environmental policy. It challenges us to reconsider the frameworks within which conservation efforts are conceptualized and implemented, urging a shift towards models that recognize and integrate local communities’ rights, knowledge, and practices. Our struggle for land rights and recognition within the framework of environmental conservation is not just a local issue but a microcosm of a global challenge: balancing the imperative of environmental protection with the rights and livelihoods of those who live in and around protected areas.

In this journey, we seek to protect our ancestral lands and redefine the conservation narrative to include the voices and wisdom of Afro-descendant communities. It is a call to acknowledge the symbiotic relationship between people and nature. It recognizes that faithful environmental stewardship requires an inclusive, equitable approach that honors the diversity of experiences, knowledge, and cultures that shape our world.

Cocles/Kekoldy

Another state-created conflict imposed upon our community began with the March 1976 creation of the Talamanca Indigenous Reserve and its subsequent boundary modifications two months later, all by executive decree. It included parts of the (ITCO)”Institute of Land and Colonization.” properties as an administrative annex to the Talamanca Indigenous Reserve, named initially the Cocles Indigenous Reserve. The delimitation of this annex was entrusted to ITCO and CONAI (National Commission for Indigenous Affairs).

A year and three months later, another executive decree expanded the reserve by about 5,700 acres with parts of other ITCO properties. However, inexplicably, it also included 3,074 acres that were not ITCO properties but predominantly lands owned by Afro-Caribbeans, located southeast of Cocles, along with about 1.4 miles of the maritime-terrestrial zone.

Five years later, the government acknowledged that the southeast part of the Cocles Indigenous Reserve had been occupied by non-Indigenous people for many years. As a result, a 1996 executive decree established that the 3,074 acres of non-Indigenous farms included in the previous decree’s delimitation were released.

As compensation for ITCO’s mistake, the Kekoldi Indigenous Reserve was expanded westward by a March 2001 executive decree, joining it with the Bribri Indigenous Reserve of Talamanca, forming a single geographical unit for the Bribri people, increasing the area of the Bribri Indigenous Reserve of Kekoldi (Cocles) to about 12,355 acres.

The Integral Development Association of the Bribri Indigenous Reserve of Këköldi (ADI-Kekoldi) sued the state, CONAI, and the Agrarian Development Institute (IDA) to recover the 3,074 acres of Afro and non-Indigenous farms. The judicial authorities restored the lands to those spelled out in the August 9, 1977, decree. It maintained the areas added as compensation, arbitrarily creating a conflict where none existed.

This decision has led to a land recovery process by the Indigenous people without compensation to the owners, including those in the maritime-terrestrial zone, affecting Afro-descendant properties and prompting conflict between two tribal peoples who previously coexisted in harmony.

The proposed solution is for INDER, in coordination with CONAI and ADI Kekoldi, to carry out the geographical delimitation of the territories comprising the Bribri Këköldi Indigenous Reserve as established by Decree in 2001, excluding properties belonging to Afro-descendants and non-Indigenous people. These boundaries should be ratified by law, as the limits set for Indigenous Territories cannot be altered to decrease their size except expressly by the law.

The Afro-tribal community acknowledges and appreciates the state’s recognition and territorial expansion granted to Indigenous peoples. However, such expansions should not come at the expense of another Afro-tribal community, mainly when the inclusion of their territories has resulted from inaccurate measurements acknowledged by the state. The state’s reliance on aerial surveys failed to recognize the longstanding presence of the Afro-descendant community, which has inhabited the area for centuries. The community emphasizes the importance of equal respect and protection of the ancestral rights of Afro-tribal communities; instead of issuing demolition orders and perpetuating the displacement of Afro-Caribbeans, we seek peaceful solutions that honor the historical and cultural significance of both communities, ensuring equitable treatment and fostering a spirit of mutual respect and coexistence.

Despite the international obligations of the Costa Rican state that prohibit it from instituting measures, whether policies, legal norms, or administrative practices, that deteriorate or worsen the situation of Afro-descendants, it has adopted a series of regressive measures such as officially repealing or suspending necessary legislation that allowed Afro-descendants to continue enjoying the rights recognized in those norms, such as the right to property titling, legal security and guarantees against evictions.

The Costa Rican state has enacted legislation and adopted policies that are manifestly incompatible with the existing national or international legal obligations regarding the rights recognized by Afro-descendants. To get really specific, for example, Law 6043 of 1977, Resolutions of the Constitutional Chamber (vote 3113-09 annuls law 8464, vote 2375-17 annuls law 9205), and Provisions of the Comptroller General’s Office (to the Ministry of Environment and Energy, report # DFOE-AE-IF-04-2011, and to the Municipality of Talamanca).

The Struggle for Recognition and Rights

The journey toward securing our rights and recognition has been long and arduous, marked by setbacks and milestones. Establishing the Afro-descendant Tribal Peoples Forum in Costa Rica represents a beacon of hope, an acknowledgment of our existence, and a platform for advocating our rights. This initiative, grounded in the principles of ILO Convention 169 and supported by the Presidential Decree on the Verification of Self-Recognition of Afro-descendant Tribal Peoples, marks a significant step forward in our quest for justice and self-determination.

Our engagement with national and international forums is not just about securing land rights; it’s about asserting our place in the world, advocating for our cultural preservation, and challenging the narratives that historically marginalized our communities. The struggle for recognition extends beyond the legal battles for land—it’s a fight for the preservation of our heritage, our language, and our traditions, which are inextricably linked to the land we call home.

The communities along the railroads that we built, and the communities of Barra del Colorado, Tortuguero, Guacimo, Siquirres, Matina, Limon, Cahuita, Puerto Viejo, Manzanillo and Sixaola, these communities predominantly of African descent have witnessed firsthand the deep-seated issues of systemic discrimination and segregation that have plagued our communities for generations. Our lands, rich in natural beauty and cultural heritage, are being stripped away by the state, a practice so normalized over the years that many of us started to accept it as inevitable. This isn’t just about losing parcels of land; it’s about the erosion of our identity and heritage.

The discrimination we face is pervasive, keeping us marginalized and silencing our voices in discussions about conservation, tourism, and national development. The railroad, which could have been a symbol of progress, instead reinforces our isolation and highlights the disparities we live with daily.

The struggle to protect our land and rights has been a relentless endeavor, passed down through generations before us. It looms over our present and, unfortunately, appears to be a looming challenge for future generations as well. We’re fighting against a system that seeks to displace and disempower us, challenging policies and practices that ignore our history and rights. It’s a struggle for the preservation of our way of life, our history, and our identity. True progress should uplift, not uproot, the communities it impacts.

Preserving Our Cultural Heritage: The Role of Education and Innovation

Our community has taken proactive steps to bridge the knowledge gap and empower our people through the Afro Costa Rica Information Initiative. By leveraging technology and innovation, we aim to enhance access to information, celebrate our rich cultural heritage and foster a sense of unity and pride among our community.

The Stanford Museum symbolizes our commitment to preserving our history and sharing our stories. More than a repository of artifacts, it is a space where our children can learn about the heroes of our past, the struggles we have overcome, and the rich tapestry of Afro-Caribbean culture that defines us. Through exhibits, workshops, and cultural events, the museum plays a crucial role in educating our community and visitors about the significance of our heritage and its preservation.

A Call to Action for Justice and Equity

As I reflect on the challenges we face and the strides we have made, I am reminded of the resilience that runs deep in our community. Our story is one of struggle but also one of hope and determination. We stand at a critical juncture in our history, where the decisions we make today will shape the future of our community for generations to come.

We call upon the Costa Rican government, international bodies and all stakeholders to recognize our rights, respect our heritage, and work with us to ensure a future where our community can thrive. As we continue to navigate the complexities of conservation, development and rights, let us remember that progress cannot be achieved at the expense of marginalized communities. We can only build a better future for all through inclusive, equitable and respectful approaches. Our journey is far from over, but with each step forward, we move closer to a world where justice, equity, and respect for all cultures and communities are not just ideals but realities.

Laylí Jeanette Tahiríh Brown Stangeland is a guardian and advocate of Afro-Caribbean heritage in Old Harbour, Cahuita, Costa Rica. Her work spans the cultural preservation of the Stanford Afro Museum and advocacy for the Afro Tribal communities’ rights in the southern Caribbean. As a businesswoman deeply connected to her roots, Laylí’s efforts highlight the resilience of Afro-Costa Rican culture. Connect with her journey through Instagram: caribecostarica, explore more at afrocostarica.com, or contact her at layli@afrocostarica.com.

El espíritu caribeño

Preservando Nuestro Patrimonio y Derechos Ancestrales

Por Layli Brown Stangeland

Nuestra comunidad y otras comunidades tribales afrodescendientes en la costa caribeña de Costa Rica se enfrentan a lo que parece ser un intento sistemático del Estado de desarraigar a nuestra comunidad. Durante décadas, Costa Rica se ha negado a otorgar títulos de propiedad e infringido nuestros derechos de propiedad al atacar la propiedad de nuestras tierras ancestrales, incluso hasta el punto de emitir órdenes de demolición.

Estamos resistiendo. Nuestra historia de resiliencia comienza en Nigeria, Gambia, las regiones ecuatoriales y occidentales de África y se extiende hasta las costas del Mar Caribe. En la exuberante selva tropical de Costa Rica, entre la sinfonía del canto de las cigarras y la danza del dosel de la selva, hemos sido autónomos a orillas del Mar Caribe durante siglos. Un pasado de lucha tejió el tapiz de la selva y el mar, dando origen a nuestra profunda conexión con nuestras tierras ancestrales.

Nací y crecí en Old Harbor, donde las hojas susurran, las olas cuentan historias y los espíritus de nuestros antepasados igbo hablan en voz baja. Como portadora de nuestra memoria colectiva del legado afrocaribeño, comparto esta rica narrativa con mi hijo, Omi, de seis años. De la mano, pisamos las mismas costas que caminaron nuestros antepasados, guiados por las estrellas, el mar Caribe y las historias, por el histórico sendero playero que nuestro pueblo recorrió a pie y a caballo, conectando el vibrante tapiz de las comunidades criollas de la costa. en Centroamérica.

“Omi”, digo mientras contemplamos el vasto mar, “tu nombre significa ‘agua’ en yoruba; esto simboliza el viaje de nuestros antepasados desde África a las Indias Occidentales hasta estas costas. Refleja nuestra fuerza, nuestra resiliencia. ” Como madre y su primera educadora, entretejo nuestra historia oral en nuestra vida diaria, asegurándose de que el legado de nuestros antepasados, sus luchas y triunfos, queden grabados en su corazón, porque él también debe vivir en esta piel.

Mi bisabuelo, William Brown Duff, era hijo del Caribe. Sólo una generación lo separó de los grilletes de la esclavitud; en sus recuerdos vivía el terror que sus abuelos compartieron sobre sus tribulaciones en su viaje a Jamaica desde Nigeria y el destino inhumano que encontraron allí. William, que entonces tenía sólo 12 años, se embarcó desde Jamaica en busca de una vida mejor. Trabajó como aguador en la construcción del Canal de Panamá, viajó por Nicaragua y finalmente, en 1918, se estableció en Costa Rica con mi bisabuela, Viola Smith, perteneciente a la familia fundadora de Cahuita. William entró en este mundo costero tropical sin darse cuenta de los desafíos que presentaría este nuevo entorno: la malaria, endémica de la selva tropical, y el clima hostil que pone a prueba constantemente la determinación de sus habitantes y, por lo tanto, la resiliencia y el espíritu indomable de nuestra comunidad negra.

Nuestros antepasados, los Bryant, Hudson, Smith y muchas más familias fundadoras del distrito de Cahuita, forjaron los pueblos del Caribe sur de Costa Rica con sus manos trabajadoras y su espíritu inquebrantable. Mientras Omi y yo caminamos por las costas arenosas, nuestros pasos nos llevan a las tierras fértiles de la granja del Sr. Edgar Campbell. El aire está lleno del rico aroma de la tierra y del cultivo de hierbas, especias, árboles frutales y plantas medicinales.“Medicina de Monte”, la abundante vitalidad de la tierra. El señor Campbell, un hombre cuya sonrisa brilla como el sol de la mañana cuando nos ve. “¡Ah, visitantes! ¡Bienvenidos, bienvenidos!” Nos saluda calurosamente. Nos aventuramos por su tierra para recoger cocos para saciar nuestra sed, con un paso que hablaba de profunda familiaridad y reverencia por la tierra, guiándonos a través de su granja, una extensión de suelo y cultivos ricos, una narrativa viva de resiliencia y herencia.

Mientras caminábamos, la tranquilidad del entorno proporcionó el telón de fondo perfecto para que Edgar contará las historias de por qué creamos las cooperativas afro como emprendimientos agrícolas de preservación cultural y ambiental. “La creación de Coopecacao Afro, como muchas otras organizaciones e iniciativas afro”, comenzó Edgar, con su voz cargando el peso de la historia que estaba a punto de contar, “era principalmente un medio para proteger nuestros derechos a la tierra”.

Compartió con nosotros cómo, en el distrito de cahuita, la tierra es más que un activo físico; es el alma de la comunidad, entrelazada con siglos de historia, cultura y sabiduría ancestral. La cooperativa surgió de una necesidad imperiosa de proteger este patrimonio de las usurpaciones de intereses externos y de afirmar la soberanía de la comunidad sobre estas tierras ancestrales. Edgar y otros miembros de nuestra comunidad se embarcaron en un viaje para gestionar de manera sostenible los recursos, aprovechando prácticas agroecológicas que honran la tierra y sus ciclos.

Cuando nos detuvimos junto a un grupo de árboles de cacao, Edgar arrancó una vaina madura de las ramas y la abrió para revelar los ricos y frescos granos del interior. “Estos”, dijo, señalando los granos, “son más que la fuente del chocolate, son un símbolo de nuestra identidad, de nuestra lucha y resiliencia. Al producir nuestro chocolate, estamos creando un producto; Estamos recuperando nuestra herencia y asegurando la supervivencia de nuestras tradiciones para las generaciones venideras”.

Omi escuchó atentamente, con sus jóvenes ojos muy abiertos ante la comprensión de las profundas historias de la tierra. La narrativa de Edgar es un relato de la práctica agrícola y una lección de administración, resistencia y el vínculo profundo entre las personas y su tierra.

A medida que continuamos nuestra caminata, la conversación giró hacia el futuro: cómo Coopecacao Afro estaba cultivando oportunidades para los jóvenes, asegurando que niños como Omi crecieran empoderados por el conocimiento de su tierra y la fuerza de sus raíces. La visión de Edgar era clara: una comunidad autosuficiente y resiliente, unida por el objetivo compartido de preservar el legado cultural y ambiental.

Nuestro viaje a través de la granja de Edgar Campbell fue un paso a través de las capas de historia, lucha y esperanza. Edgar se volvió hacia Omi, su mirada a la vez severa y cálida. “Recuerda, joven”, comenzó con voz firme pero imbuida de una bondad casi paternal, “la granja de un hombre negro es su despensa”.

Hizo una pausa, permitiendo que el peso de sus palabras asimilara, y luego continuó: “Es crucial para nosotros confiar en nosotros mismos, nutrir a nuestra comunidad y a nuestras familias con lo que la tierra nos regala”. Con un gesto que abarcó la extensión de su granja, compartió la esencia de su sabiduría: “Aquí cultivamos más que solo alimentos: cultivamos vida. Desde los cultivos que nos alimentan hasta las hierbas medicinales que nos curan, como el ‘ BUSH TEA’, asegúrate de beber ‘bear bush’, cada parte de esta tierra nos sustenta”. La despedida de Edgar con nosotros incluyó una cita de Marcus Mosaih Garvey, recordándonos que “un pueblo sin conocimiento de su historia pasada, origen y cultura es como un árbol sin raíces”. Cuando salimos de la granja, el sol poniente proyectaba una luz dorada sobre nosotros. los campos, pude ver una nueva comprensión reflejada en la mirada de Omi. Fue un reconocimiento de la importancia de las raíces, de la tierra y de las historias que nos unen a ambas.

La batalla invisible de las comunidades afrodescendientes de Costa Rica

En Costa Rica, una nación reconocida por su dedicación a la paz y la conservación del medio ambiente, se encuentra una narrativa menos visible que contrasta marcadamente con su imagen idílica. Esta narrativa nos pertenece a nosotros, las comunidades afrodescendientes de la costa caribeña, que nos encontramos atrapados en una lucha contra las leyes que amenazan nuestra existencia en nuestros territorios ancestrales. A pesar del reconocimiento internacional de Costa Rica por sus exuberantes bosques tropicales y su compromiso con la preservación ecológica, nuestra historia revela una realidad diferente, una en la que los principios del ambientalismo justifican el desplazamiento de comunidades afro con vínculos históricos y culturales profundamente arraigados a estas tierras.

Los desafíos de la raza y el racismo en América Latina y el Caribe son complejos y generalizados, y Costa Rica no es una excepción. Nuestros territorios (las tierras que nuestros antepasados han nutrido, cultivado, en gran armonía con la naturaleza y que han llamado hogar durante generaciones) están bajo asedio. Esta realidad trasciende las fronteras, los idiomas y las historias nacionales, uniéndonos a otras poblaciones afrodescendientes en una lucha compartida por el reconocimiento y los derechos. El enfoque de Costa Rica para gestionar sus recursos ambientales bajo el pretexto de la conservación ha llevado al desarraigo sistemático de nuestras comunidades. Esta sofisticada mascarada de gestión ecológica, que ha cosechado elogios internacionales, enmascara una amarga verdad: el desplazamiento de personas con el pretexto de proteger la naturaleza.

La ironía de esta situación es profunda. Mientras Costa Rica recibe elogios por sus iniciativas ambientales, las tierras y tradiciones de las comunidades afrocaribeñas se están erosionando silenciosamente. Nuestros derechos, historias e identidades son arrastrados por la llamada marea del progreso, dejándonos enfrentar las ramificaciones de políticas que no reconocen nuestra existencia y nuestras contribuciones al tejido cultural y ecológico de la nación. Este escenario subraya los desafíos y logros relacionados con la raza y el racismo en Costa Rica, revelando una nación que lucha con problemas profundamente arraigados de desplazamiento racial y discriminación, todo bajo el barniz de ambientalismo.

Un legado ignorado y amenazado

La Constitución de Costa Rica, con sus reformas que enfatizan una sociedad multiétnica y pluricultural, promete igualdad, derechos de propiedad y protección del medio ambiente. Estos marcos legales pretendían anunciar una nueva era, reconociendo el diverso entramado de culturas que constituyen la nación. Sin embargo, la realidad para las comunidades afrodescendientes, particularmente en regiones como Limón, contrasta marcadamente con estas promesas constitucionales. A pesar del reconocimiento legal, seguimos navegando por un panorama empañado por la discriminación sistémica, la exclusión y la amenaza inminente de desplazamiento, un crudo recordatorio del abismo entre los ideales legales y su implementación.

Casi una década después de estas enmiendas constitucionales, las comunidades afrodescendientes de Costa Rica siguen envueltas en una lucha por el reconocimiento, luchando contra barreras sistémicas que obstaculizan nuestro acceso a la justicia, la educación y el trato equitativo. El caribe de la provincia de Limón se ha convertido en un campo de batalla por nuestros derechos. El principio de irretroactividad, destinado a proteger los derechos adquiridos, y las promesas de igualdad ante la ley parecen disolverse ante las realidades del distrito de Cahuita y otros pueblos afro. -Los asentamientos de descendientes, nuestras tierras ancestrales, están ahora amenazados. Están clasificados bajo leyes que anulan nuestros reclamos y nuestra existencia. Si bien sus intenciones son nobles, las regulaciones ambientales y los esfuerzos de conservación se han aplicado de maneras que afectan desproporcionadamente a nuestras comunidades de manera negativa. Esta creación del Instituto de Tierras y Colonización en 1961, entidad que implementó un masivo programa de titulación de tierras a nombre del Estado, desconoció los derechos ancestrales de nuestro pueblo, incluidos los cementerios familiares públicos y privados. El Estado ha reclamado la propiedad de nuestras tierras e incluso de los restos de nuestros antepasados, una medida que irónicamente coincidió con el momento en que a los negros se les dio el derecho a votar y participar en el gobierno.

La lucha contra “Ley sobre la Zona Marítimo Terrestre” 6043

La Ley de Zona Marítima(Ley N° 6043) es un punto focal crítico porque la legislación que rige la zona marítima costera amenaza con desplazar a nuestras comunidades ancestrales afrodescendientes. La ley aparentemente apunta a proteger y gestionar la costa para el bien público, enfatizando la conservación y el desarrollo responsable. Sin embargo, la realidad de nuestras comunidades afrodescendientes, cuyas vidas y medios de subsistencia están intrínsecamente ligados a estas tierras, cuenta una historia de desplazamiento y privación de derechos, que los objetivos ambientales de la ley pasan por alto.

Nuestros antepasados, que históricamente cultivaron esta tierra y dependen del mar para su sustento, se encuentran en desacuerdo con una ley que no reconoce su existencia. La ley declara la zona marítima costera como inalienable e imprescriptible, despojándonos efectivamente de cualquier reclamo sobre estas tierras, independientemente de cuánto tiempo las hayamos habitado. Ordena que las áreas frente a la playa dentro de los primeros 50 metros (164 pies) desde la línea de marea alta sean designadas como espacio público y los siguientes 150 metros (492 pies) como restringidos estén bajo control estatal, desplazando a las comunidades históricas que han existido mucho antes de estos. leyes.

Nuestras practicas de pesca, el cultivo de coco y la utilización de remedios arbustivos (tradiciones transmitidas de generación en generación) están ahora amenazados. Las responsabilidades de supervisión conferidas al Instituto Costarricense de Turismo y los mandatos de cumplimiento directo para los municipios complican aún más nuestra lucha. Si bien la ley describe un marco integral para la protección y gestión de las zonas costeras, es evidente que no incorpora los derechos y las voces de las comunidades afrodescendientes. Nuestros hogares y negocios ancestrales están marcados para su demolición, etiquetados como obstrucciones a las visiones ambientales y de desarrollo del estado.

Esta situación jurídica se ve agravada por desastres naturales, como el terremoto que provocó la licuefacción del suelo en la provincia de Limón, desestabilizando aún más a nuestras comunidades y acercando la costa a nuestros hogares. El aumento de hasta 6,2 pies en la costa costarricense facilitó la justificación del Estado para demoler nuestras casas y desarraigar a nuestras comunidades, citando la necesidad de recuperar la zona marítima ampliada.

Esta ley y su implementación encarnan los desafíos más amplios que enfrentamos para garantizar nuestros derechos y preservar nuestro patrimonio. Nuestra lucha contra esta legislación no es una postura contra la conservación, porque siempre hemos vivido en armonía con la naturaleza, sino un llamado a un enfoque más inclusivo y equitativo que reconozca y respete los derechos de todas las comunidades, especialmente las de ascendencia africana, que han sido administradores de estas tierras mucho antes de su designación actual como áreas protegidas.

La “Ley sobre la Zona Marítimo Terrestre” representa un momento crítico en nuestra lucha continua por el reconocimiento, la justicia y el derecho a vivir en armonía con las tierras que nuestros antepasados han cultivado durante siglos. Subraya la necesidad de diálogo, de leyes que protejan el medio ambiente y defiendan los derechos y tradiciones de las comunidades que han convivido con estos espacios naturales. Nuestro llamado es por una reevaluación de esta legislación, por políticas que reconozcan nuestra presencia histórica y por un futuro en el que nuestros hijos, puedan seguir prosperando en las tierras de sus antepasados, libres de la amenaza del desplazamiento y la eliminación.

La ironía de la conservación y el impacto en las comunidades afrodescendientes

La creación del Parque Nacional Tortuguero en la década de 1970 marcó el comienzo de una era de conservación que, si bien es crucial para la lucha global contra la degradación ambiental, sin darse cuenta preparó el escenario para el desplazamiento sistemático de nuestra gente. Ubicado en la exuberante provincia de Limón, este parque, un paraíso para la biodiversidad, se convirtió en uno de los primeros campos de batalla donde se desarrolló la compleja relación entre los objetivos de conservación y los derechos comunitarios. La creación del parque y áreas protegidas posteriores como el Refugio de Vida Silvestre Barra del Colorado no sólo destacó el compromiso de la nación con la preservación del medio ambiente, sino que también subrayó un descuido flagrante: la falta de considerar adecuadamente el impacto de estas iniciativas en las poblaciones afrodescendientes.

La expansión de las áreas de conservación a lo largo de las décadas de 1970 y 1990, incluido el establecimiento del Refugio de Vida Silvestre Gandoca-Manzanillo y la designación del Parque Nacional Cahuita, complicó aún más las vidas de quienes se encontraban dentro de sus límites. Nuestros vínculos ancestrales con estas tierras, anteriores al establecimiento de áreas protegidas, aparentemente fueron ignorados en favor de una narrativa de conservación más amplia. Esta disonancia entre los objetivos de preservación ambiental y los derechos de las comunidades indígenas y afrodescendientes a sus tierras ancestrales resalta una brecha crítica en el discurso de la conservación. Esta brecha pasa por alto la dimensión humana de la gestión ambiental.

La historia de la conservación en Costa Rica, particularmente en el contexto de las comunidades afrodescendientes, es un recordatorio conmovedor de la necesidad de un enfoque más inclusivo de la política ambiental. Nos desafía a reconsiderar los marcos dentro de los cuales se conceptualizan e implementan los esfuerzos de conservación, instando a un cambio hacia modelos que reconozcan e integren los derechos, conocimientos y prácticas de las comunidades locales. Nuestra lucha por los derechos a la tierra y el reconocimiento dentro del marco de la conservación ambiental no es sólo una cuestión local sino un microcosmos de un desafío global: equilibrar el imperativo de la protección ambiental con los derechos y medios de vida de quienes viven en y alrededor de áreas protegidas.

En este viaje, buscamos proteger nuestras tierras ancestrales y redefinir la narrativa de conservación para incluir las voces y la sabiduría de las comunidades afrodescendientes. Es un llamado a reconocer la relación simbiótica entre las personas y la naturaleza. Reconoce que una gestión ambiental fiel requiere un enfoque inclusivo y equitativo que respete la diversidad de experiencias, conocimientos y culturas que dan forma a nuestro mundo.

Cocles / Kekoldi

Otro conflicto creado por el Estado impuesto a nuestra comunidad comenzó con la creación en marzo de 1976 de la Reserva Indígena de Talamanca y sus posteriores modificaciones de límites dos meses después, todo por decreto ejecutivo. Incluía partes del (ITCO) “Instituto de Tierras y Colonización”. propiedades como anexo administrativo de la Reserva Indígena de Talamanca, denominada inicialmente Reserva Indígena Cocles. La delimitación de este anexo fue encomendada a ITCO y CONAI (Comisión Nacional de Asuntos Indígenas).

Un año y tres meses después, otro decreto ejecutivo amplió la reserva en unas 5.700 hectáreas con partes de otras propiedades de ITCO. Sin embargo, inexplicablemente, también incluía 3.074 acres que no eran propiedades de ITCO sino predominantemente tierras propiedad de afrocaribeños, ubicado al sureste de Cocles, a lo largo de aproximadamente 1,4 millas de la zona marítimo-terrestre.

Cinco años después, el gobierno reconoció que la parte sureste de la Reserva Indígena de Cocles había estado ocupada por no indígenas durante muchos años. Como resultado, un decreto ejecutivo de 1996 estableció que las 3.074 hectáreas de fincas no indígenas incluidas en la delimitación del decreto anterior fueron liberadas.

Como compensación por el error del ITCO, la Reserva Indígena Kekoldi se amplió hacia el oeste mediante un decreto ejecutivo de marzo de 2001, uniéndose con la Reserva Indígena Bribri de Talamanca, formando una unidad geográfica única para el pueblo Bribri, aumentando el área de la Reserva Indígena Bribri de Kekoldi. (Cocles) a aproximadamente 12,355 acres.

La Asociación de Desarrollo Integral de la Reserva Indígena Bribri de Këköldi (ADI-Kekoldi) demandó al Estado, a la CONAI y al Instituto de Desarrollo Agrario (IDA) para recuperar las 3.074 hectáreas de fincas afro y no indígenas. Las autoridades judiciales restituyeron las tierras a las señaladas en el decreto del 9 de agosto de 1977. Mantuvo las áreas agregadas como compensación, creando arbitrariamente un conflicto donde no existía.

Esta decisión ha dado lugar a un proceso de recuperación de tierras por parte de los pueblos indígenas sin compensación a sus propietarios, incluidos los de la zona marítimo-terrestre, afectando propiedades afrodescendientes y provocando un conflicto entre dos pueblos tribales que anteriormente conviven en armonía.

La solución propuesta es que el INDER, en coordinación con la CONAI y la ADI Kekoldi, realice la delimitación geográfica de los territorios que componen la Reserva Indígena Bribri Këköldi según lo establecido por Decreto de 2001, excluyendo las propiedades pertenecientes a afrodescendientes y no indígenas. Estos límites deben ser ratificados por ley, ya que los límites establecidos para los Territorios Indígenas no pueden alterarse para disminuir su tamaño excepto expresamente por ley.

La comunidad afro tribal reconoce y valora el reconocimiento estatal y la expansión territorial otorgado a los pueblos indígenas. Sin embargo, tales expansiones no deberían realizarse a expensas de otra comunidad afro tribal, principalmente cuando la inclusión de sus territorios ha sido el resultado de mediciones inexactas reconocidas por el Estado. La dependencia del Estado de los reconocimientos aéreos no reconoció la presencia de larga data de la comunidad afrodescendiente, que ha habitado la zona durante siglos. La comunidad enfatiza la importancia del igual respeto y protección de los derechos ancestrales de las comunidades afro tribales; en lugar de emitir órdenes de demolición y perpetuar el desplazamiento de los afrocaribeños, buscamos soluciones pacíficas que honren la importancia histórica y cultural de ambas comunidades, garantizando un trato equitativo y fomentando un espíritu de respeto mutuo y coexistencia.

A pesar de las obligaciones internacionales del Estado costarricense que le prohíben instituir medidas, ya sean políticas, normas legales o prácticas administrativas, que deterioren o empeoren la situación de los afrodescendientes, ha adoptado una serie de medidas regresivas como derogar oficialmente o suspendiendo legislación necesaria que permitió a los afrodescendientes seguir disfrutando de derechos reconocidos en esas normas, como el derecho a la titulación de propiedad, la seguridad jurídica y las garantías contra los desalojos.

El Estado costarricense ha promulgado legislación y adoptado políticas que son manifiestamente incompatibles con las obligaciones jurídicas nacionales o internacionales existentes respecto de los derechos reconocidos a las personas afrodescendientes. Para ser muy específicos, por ejemplo, la Ley 6043 de 1977, Resoluciones de la Sala Constitucional (voto 3113-09 anula ley 8464, voto 2375-17 anula la ley 9205), y Disposiciones de la Contraloría General (al Ministerio de Ambiente y Energía, informe #DFOE-AE-IF-04-2011, y al Municipio de Talamanca).

La lucha por el reconocimiento y los derechos

El camino hacia la garantía de nuestros derechos y reconocimiento ha sido largo y arduo, marcado por reveses e hitos. El establecimiento del Foro de Pueblos Tribales Afrodescendientes en Costa Rica representa un rayo de esperanza, un reconocimiento de nuestra existencia y una plataforma para defender nuestros derechos. Esta iniciativa, basada en los principios del Convenio 169 de la OIT y respaldada por el Decreto Presidencial sobre la Verificación del Autoreconocimiento de los Pueblos Tribales Afrodescendientes, marca un importante paso adelante en nuestra búsqueda de justicia y autodeterminación.

Nuestro compromiso con foros nacionales e internacionales no se trata sólo de garantizar los derechos sobre la tierra; se trata de afirmar nuestro lugar en el mundo, abogar por nuestra preservación cultural y desafiar las narrativas que históricamente marginaron a nuestras comunidades. La lucha por el reconocimiento se extiende más allá de las batallas legales por la tierra: es una lucha por la preservación de nuestro patrimonio, nuestro idioma y nuestras tradiciones, que están inextricablemente vinculados a la tierra que llamamos hogar.

Las comunidades a lo largo de los ferrocarriles que construimos, y las comunidades de Barra del Colorado, Tortuguero, Guácimo, Siquirres, Matina, Limón, Cahuita, Puerto Viejo, Manzanillo y Sixaola, estas comunidades predominantemente de ascendencia africana, han sido testigos de primera mano de los problemas profundamente arraigados de discriminación y segregación sistémicas que han afectado a nuestras comunidades durante generaciones. Nuestras tierras, ricas en belleza natural y patrimonio cultural, están siendo despojadas por el Estado, una práctica tan normalizada a lo largo de los años que muchos de nosotros comenzamos a aceptarla como inevitable. No se trata sólo de perder parcelas de tierra; se trata de la erosión de nuestra identidad y herencia.

La discriminación que enfrentamos es generalizada, nos mantiene marginados y silencia nuestras voces en las discusiones sobre conservación, turismo y desarrollo nacional. El ferrocarril, que podría haber sido un símbolo de progreso, en cambio refuerza nuestro aislamiento y resalta las disparidades con las que vivimos a diario.

La lucha para proteger nuestra tierra y nuestros derechos ha sido un esfuerzo incesante, transmitido de generación en generación antes que nosotros. Se cierne sobre nuestro presente y, lamentablemente, parece ser también un desafío inminente para las generaciones futuras. Estamos luchando contra un sistema que busca desplazarnos y quitarnos poder, desafiando políticas y prácticas que ignoran nuestra historia y nuestros derechos. Es una lucha por la preservación de nuestra forma de vida, nuestra historia y nuestra identidad. El verdadero progreso debería elevar, no desarraigar, a las comunidades a las que afecta.

Preservar nuestro patrimonio cultural: el papel de la educación y la innovación

Nuestra comunidad ha tomado medidas proactivas para cerrar la brecha de conocimiento y empoderar a nuestra gente a través de la Afro Costa Rica Iniciativa de información. Al aprovechar la tecnología y la innovación, nuestro objetivo es mejorar el acceso a la información, celebrar nuestro rico patrimonio cultural y fomentar un sentido de unidad y orgullo entre nuestra comunidad.

El Museo de Stanford simboliza nuestro compromiso de preservar nuestra historia y compartir nuestras historias. Más que un depósito de artefactos, es un espacio donde nuestros niños pueden aprender sobre los héroes de nuestro pasado, las luchas que hemos superado y el rico tapiz de la cultura afrocaribeña que nos define. A través de exhibiciones, talleres y eventos culturales, el museo juega un papel crucial en educar a nuestra comunidad y a los visitantes sobre la importancia de nuestro patrimonio y su preservación.

Un llamado a la acción por la justicia y la equidad

Al reflexionar sobre los desafíos que enfrentamos y los avances que hemos logrado, recuerdo la resiliencia que está profundamente arraigada en nuestra comunidad. Nuestra historia es de lucha pero también de esperanza y determinación. Nos encontramos en un momento crítico de nuestra historia, donde las decisiones que tomemos hoy moldearán el futuro de nuestra comunidad para las generaciones venideras.

Hacemos un llamado al gobierno costarricense, a los organismos internacionales y a todas las partes interesadas a reconocer nuestros derechos, respetar nuestro patrimonio y trabajar con nosotros para garantizar un futuro en el que nuestra comunidad pueda prosperar. Mientras continuamos navegando por las complejidades de la conservación, el desarrollo y los derechos, recordemos que el progreso no se puede lograr a expensas de las comunidades marginadas. Sólo podemos construir un futuro mejor para todos mediante enfoques inclusivos, equitativos y respetuosos. Nuestro viaje está lejos de terminar, pero con cada paso adelante, nos acercamos a un mundo donde la justicia, la equidad y el respeto por todas las culturas y comunidades no sean sólo ideales sino realidades.

Laylí Jeanette Tahiríh Brown Stangelandes guardián y defensor de la herencia afrocaribeña en Old Harbour, Cahuita, Costa Rica. Su trabajo abarca la preservación cultural del Museo Afro de Stanford y la defensa de los derechos de las comunidades tribales afro en el sur del Caribe. Como empresaria profundamente conectada con sus raíces, los esfuerzos de Laylí resaltan la resiliencia de la cultura afrocostarricense. Conéctate con su viaje a través de Instagram:caribecostarica, explora más enafrocostarica.com, o póngase en contacto con ella enlayli@afrocostarica.com.

Di Caribbean spirit

Preserving Wi Heritage and Ancestral Rights

By Layli Brown Stangeland

Wi community and odda Afro-descendant tribal communities pon Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast a face weh seem like a systematic attempt by di state fi root out wi community. Fi decades, Costa Rica nah gi wi property titles and infringe pon wi rights to property by targeting ownership over wi ancestral lands, even to di point of issuing demolition orders.

Wi a resist. Wi story of resilience start in Nigeria, Gambia, Equatorial and Western regions in Africa, stretching to di shores of di Caribbean Sea. Inna di lush tropical rainforest of Costa Rica, between di symphony of cicada singing and di dance of di jungle canopy, we been autonomous pon di shores of di Caribbean Sea fi centuries. A past of struggle weave di tapestry of di rainforest and sea, giving rise to wi deep connection wid wi ancestral lands.

Mi born and grow in Old Harbor, where leaves whisper, waves tell tales, and di spirits of wi Igbo ancestors softly speak. As a bearer of wi collective memory of di Afro-Caribbean legacy, mi share dis rich narrative wid mi son, Omi, age six. Hand in hand, we walk di very shores wi ancestors once walk, guided by stars, di Caribbean sea and stories, along di historical beach path weh wi people journeyed by foot and by horse, connecting di vibrant tapestry of di Creole communities of di coast in Central America.

“Omi,” mi say, as we gaze across di vast sea, “yuh name means ‘water’ in Yoruba; dis symbolize di journey of wi ancestors from Africa to di West Indies to these shores. It reflects wi strength, wi resilience.” As a mother and him first educator, mi weave wi oral history into wi daily lives, ensuring dat di legacy of wi ancestors, dem struggles and triumphs, are etched inna him heart, for him, too, must live inna dis skin.

Mi great-grandfather, William Brown Duff, was a son of di Caribbean. Only one generation separated him from di shackles of enslavement; inna him memories lived di terror him grandparents shared of dem travails on dem voyage to Jamaica from Nigeria and di subhuman fate dem meet deh. William, just 12 years old at di time, embark from Jamaica in search of a better life. Him work as a water carrier in constructing di Panama Canal, traveled through Nicaragua, and finally, in 1918, settled in Costa Rica with mi great-grandmother, Viola Smith, belonging to di founding family of Cahuita. William enter dis tropical coastal world unaware of di challenges dis new environment would present: malaria, endemic to di rainforest, and di hostile climate constantly testing di resolve of its inhabitants, thus, di resilience and indomitable spirit of wi Black community.

Wi ancestors, di Bryants, Hudsons, Smiths, and many more of di founding families of Cahuita’s district, forge di towns of di southern Caribbean of Costa Rica with dem work-rough hands and unbreakable spirits. As Omi and mi walk di sandy shores, wi steps lead wi to di fertile grounds of Mr. Edgar Campbell’s farm. Di air filled with di rich scent of earth and growing herbs, spices, fruit trees and medicinal plants “Bush Medicine”, di land’s abundant vitality. Mr. Campbell, a man whose smile beams like di morning sun as him spot wi. “Ah, visitors! Welcome, welcome!” Him greet wi warmly. Wi venture through him land to pick coconuts to quench wi thirst, with a stride dat spoke of deep familiarity and reverence for di land, guiding wi through him farm, an expanse of rich soil and crops, a living narrative of resilience and heritage.

As wi walked, di tranquility of di surroundings provided di perfect backdrop for Edgar to unfold di stories of why wi create Afro cooperatives as agricultural ventures of cultural and environmental preservation. “Di creation of Afro cooperatives, as many more afro organizations and initiatives” Edgar begin, him voice carrying di weight of di story him was about to tell, “was primarily a means to protect wi land rights.”

Him shared with wi how, inna di district of Cahuita, di land is more than a physical asset; it’s di soul of di community, entwined with centuries of history, culture, and ancestral wisdom. Di cooperative emerge from a dire need to shield dis heritage from di encroachments of external interests and to assert di community’s sovereignty over these ancestral lands. Edgar and fellow members inna wi community embark pon a journey to sustainably manage resources, leveraging agroecological practices that honor di earth and its cycles.

As wi paused by a patch of cacao trees, Edgar pluck a ripe pod from di branches, splitting it open to reveal di rich, fresh beans inside. “These,” him say, gesturing towards di beans, “are more than di source of chocolate, dem a symbol of wi identity, of wi struggle and resilience. By producing wi chocolate, wi a create a product; wi a reclaim wi heritage and ensuring di survival of wi traditions for generations to come.”

Omi listen intently, him young eyes wide with di unfolding realization of di land’s deep stories. Edgar’s narrative is an account of agricultural practice and a lesson in stewardship, resistance, and di profound bond between people and dem land.

As wi continued wi walk, di conversation shift to di future—how Afro cooperatives a cultivate opportunities for di youth, ensuring that children like Omi would grow up empowered by di knowledge of dem land and di strength of dem roots. Edgar’s vision was clear: a community self-sufficient and resilient, bound by di shared goal of preserving di cultural and environmental legacy.

Wi journey through Edgar Campbell’s farm was a passage through di layers of history, struggle, and hope.. Edgar turn to Omi, him gaze both stern and warm. “Remember, young man,” him begin, him voice firm yet imbued with an almost paternal kindness, “a Black man’s farm is him pantry.”

He paused, allowing di weight of him words to sink in, then continued, “It crucial for wi fi depend pon wi self, fi nurture wi community and wi families with what di earth gi wi.” With a gesture dat take in di whole expanse of him farm, him share di essence of him wisdom, “Here, wi nuh just grow food; wi cultivate life. From di crops that feed wi to di medicinal herbs weh heal wi, like di ‘BUSH TEA’ mek sure yuh drink ‘bear bush,’ every part a dis land sustain wi.” Edgar’s farewell to wi include a quote by Marcus Mosaih Garvey, reminding wi seh “a people without knowledge of dem past history, origin, and culture is like a tree without roots.” As wi lef di farm, di setting sun casting golden light over di fields, mi could see a new understanding reflected in Omi’s gaze. It was a recognition of di importance of roots, of land, and of di stories that bind wi to both.

Di Unseen Battle of Costa Rica’s Afro-Descendant Communities

Inna Costa Rica, a nation renowned fi its dedication to peace and environmental conservation, deh a less visible narrative weh contrast sharply with its idyllic image. Dis narrative belong to we, di Afro-descendant communities of di Caribbean coast, weh find weself trapped inna a struggle against laws weh threaten fi wi very existence pon wi ancestral grounds. Despite Costa Rica’s international acclaim fi its lush rainforests and commitment to ecological preservation, wi story reveal a different reality—one in which di principles of environmentalism justify di displacement of Afro-communities with deep-rooted historical and cultural ties to dem lands.

Di challenges of race and racism inna Latin America and di Caribbean complex and pervasive, and Costa Rica nah no exception. Wi territories—di lands wi ancestors have nurtured, cultivated, in great harmony with nature and called home fi generations—under siege. Dis reality transcend national borders, languages and histories, uniting wi with odda Afro-descendant populations inna a shared struggle fi recognition and rights. Costa Rica’s approach to managing its environmental resources under di guise of conservation lead to di systematic uprooting of wi communities. Dis sophisticated masquerade of ecological stewardship, weh get international praise, mask a bitter truth: di displacement of people under di pretext of protecting nature.

Di irony of dis situation profound. As Costa Rica get accolades fi its environmental initiatives, di lands and traditions of Afro-Caribbean communities quietly being eroded. Wi rights, histories and very identities swept away inna di so-called tide of progress, leaving wi fi contend with di ramifications of policies weh fail fi acknowledge wi existence and contributions to di cultural and ecological fabric of di nation. Dis scenario underscore di challenges and achievements concerning race and racism inna Costa Rica, revealing a nation grappling with deep-seated issues of racial displacement and discrimination, all under di veneer of environmentalism.

A Legacy Overlooked and Under Threat

Di Constitution of Costa Rica, with its amendments emphasizing a multiethnic and pluricultural society, promise equality, property rights and environmental protection. Dem legal frameworks intended to herald a new era, recognizing di diverse tapestry of cultures weh constitute di nation. However, di reality fi Afro-descendant communities, particularly in regions like Limon, sharply contrast with these constitutional promises. Despite legal recognition, wi continue fi navigate a landscape marred by systemic discrimination, exclusion and di looming threat of displacement—a stark reminder of di chasm between legal ideals and dem implementation.

Nearly a decade since dem constitutional amendments, di Afro-descendant communities of Costa Rica remain embroiled inna a struggle fi recognition, battling systemic barriers weh hinder wi access to justice, education and equitable treatment. Di Caribbean of Limon province become a battleground fi wi rights.Di principle of non-retroactivity, meant to protect acquired rights, and di promises of equality before di law seem fi dissolve when faced with di realities of di district of Cahuita and odda Afro-descendant settlements, wi ancestral lands, now under threat. Dem classify under laws weh render wi claims and existence void. While noble inna dem intentions, environmental regulations and conservation efforts have been applied in ways weh disproportionately affect wi communities in negative ways. Di creation of di Institute of Land and Colonization inna 1961, an entity weh enact a massive program of land titling inna di name of di state, disregarded di ancestral rights of wi people, including public and private family cemeteries. Di state claim ownership over wi lands and even wi ancestors’ remains, a move weh ironically coincide with di time in which Blacks were given di right fi vote and participate inna government.

Di Struggle Against “Ley sobre la Zona Marítimo Terrestre” 6043

Di Maritime Zone Law (Law No. 6043) a critical focal point because di legislation governing di coastal maritime zone threaten fi displace wi ancestral communities of African Descent. Di law ostensibly aim fi protect and manage di coast fi di public good, emphasizing conservation and responsible development. However, di reality fi wi Afro-descendant communities, whose lives and livelihoods intrinsically tied to dem lands, tell a story of displacement and disenfranchisement, glossed over by di law’s environmental objectives.

Wi ancestors, weh historically cultivate dis land and rely pon di sea fi sustenance, find demself at odds with a law weh nah recognize dem existence. Di law declare di coastal maritime zone as inalienable and imprescriptible, effectively stripping wi of any claim to dem lands, regardless of how long wi inhabit dem. It mandate that beachfront areas within di first 50 meters (164 feet) from di high tide line designated as public space and di subsequent 150 meters (492 feet) as restricted are under state control, ousting di historical communities weh exist much before dem laws.

Wi practices of fishing, coconut cultivation and di utilization of bush remedies—traditions passed down through generations—now under threat. Di oversight responsibilities vested inna di Costa Rican Tourism Institute and di direct compliance mandates fi municipalities further complicate wi struggle. While di law outline a comprehensive framework fi protecting and managing di coastal zones, it starkly fail fi incorporate di rights and voices of di Afro-descendant communities. Wi ancestral homes and businesses marked fi demolition, labeled as obstructions to di state’s environmental and developmental visions.

Dis legal situation exacerbated by natural disasters, such as di earthquake weh lead to soil liquefaction inna Limón province, further destabilizing wi communities and bringing di coastline closer to wi homes. Di rise inna di Costa Rican coastline by up to 6.2 feet facilitate di state justification fi demolishing wi homes and uprooting wi communities, citing di need fi reclaim di expanded maritime zone.

Dis law and its implementation embody di broader challenges wi face inna securing wi rights and preserving wi heritage. Wi fight against dis legislation nah a stand against conservation, for wi always live harmoniously with nature, but a call fi a more inclusive, equitable approach weh recognize and respect di rights of all communities, ‘specially those of African descent, weh been stewards of dem lands long before dem current designation as protected areas.

Di “Ley sobre la Zona Marítimo Terrestre” represent a critical juncture inna wi ongoing struggle fi recognition, justice and di right fi live in harmony with di lands wi ancestors cultivate fi centuries. It underscore di need fi dialogue, fi laws weh protect di environment and uphold di rights and traditions of di communities weh coexist with dem natural spaces. Wi plea a fi a reevaluation of dis legislation, fi policies weh acknowledge wi historical presence, and fi a future where wi children can continue fi thrive pon di lands of dem forebears, free from di threat of displacement and erasure.

Conservation’s Irony and di Impact pon Afro-descendant Communities

Di creation of Tortuguero National Park inna di 1970s mark di beginning of a conservation era weh, while crucial fi di global fight against environmental degradation, inadvertently set di stage fi di systematic displacement of wi people. Nestled inna di lush province of Limón, dis park, a haven fi biodiversity, become one of di first battlegrounds where di complex relationship between conservation objectives and community rights unfold. Di creation of di park and subsequent protected areas like di Barra del Colorado Wildlife Refuge not only highlight di nation commitment to environmental preservation but also underscore a glaring oversight: di failure to adequately consider di impact of dem initiatives pon di Afro-descendant populations.

Di expansion of conservation areas throughout di 1970s and 1990s, including di establishment of di Gandoca-Manzanillo Wildlife Refuge and di designation of Cahuita National Park, further complicate di lives of those within dem boundaries. Wi ancestral ties to dem lands, predating di establishment of protected areas, were seemingly disregarded in favor of a broader conservation narrative. Dis dissonance between di goals of environmental preservation and di rights of indigenous and Afro-descendant communities to dem ancestral lands highlight a critical gap inna di conservation discourse. Dis gap overlook di human dimension of environmental stewardship.

Di conservation story inna Costa Rica, particularly inna di context of Afro-descendant communities, a poignant reminder of di need fi a more inclusive approach to environmental policy. It challenge wi fi reconsider di frameworks within which conservation efforts conceptualized and implemented, urging a shift towards models weh recognize and integrate local communities’ rights, knowledge, and practices. Wi struggle fi land rights and recognition within di framework of environmental conservation nah just a local issue but a microcosm of a global challenge: balancing di imperative of environmental protection with di rights and livelihoods of those weh live inna and around protected areas.

Inna dis journey, wi seek fi protect wi ancestral lands and redefine di conservation narrative fi include di voices and wisdom of Afro-descendant communities. It a call fi acknowledge di symbiotic relationship between people and nature. It recognize say faithful environmental stewardship require an inclusive, equitable approach weh honor di diversity of experiences, knowledge, and cultures weh shape wi world.

Cocles/Kekoldy

Aneda conflict weh di state create an impose pon wi community start back inna March 1976 wid di creation of di Talamanca Indigenous Reserve an its boundary modifications two months later, all by executive decree. It include parts of di (ITCO)”Institute of Land and Colonization.” properties as an administrative annex to di Talamanca Indigenous Reserve, initially named di Cocles Indigenous Reserve. Di task fi outline dis annex was gi to ITCO an CONAI (National Commission for Indigenous Affairs).

A year an three months after, aneda executive decree expand di reserve by about 5,700 acres wid parts of odda ITCO properties. But, fi some reason we cyaan explain, it also include 3,074 acres weh neva did a ITCO properties but mainly lands owned by Afro-Caribbeans, located southeast of Cocles, along wid about 1.4 miles of di maritime-terrestrial zone.

Five years down di line, di government recognize seh di southeast part of di Cocles Indigenous Reserve did have non-Indigenous people a live pon it fi many years. So, a 1996 executive decree mek it known seh di 3,074 acres of non-Indigenous farms included inna di previous decree’s boundary were released.

As compensation fi ITCO’s mistake, di Kekoldi Indigenous Reserve get expand westward by a March 2001 executive decree, joining it wid di Bribri Indigenous Reserve of Talamanca, forming one big geographical unit fi di Bribri people, making di area of di Bribri Indigenous Reserve of Kekoldi (Cocles) about 12,355 acres big.

Di Integral Development Association of di Bribri Indigenous Reserve of Këköldi (ADI-Kekoldi) tek di state, CONAI, an di Agrarian Development Institute (IDA) go court fi get back di 3,074 acres of Afro and non-Indigenous farms. Di judicial authorities give back di lands as per di August 9, 1977, decree. It keep di areas added as compensation, creating a conflict weh neva did deh before.

Dis decision lead to a land recovery process by di Indigenous people without no compensation to di owners, including those inna di maritime-terrestrial zone, affecting Afro-descendant properties an causing conflict between two tribal peoples weh did live inna peace before.

Di proposed solution a fi INDER, in coordination wid CONAI an ADI Kekoldi, fi do di geographical delimitation of di territories weh mek up di Bribri Këköldi Indigenous Reserve as set by Decree in 2001, excluding properties belonging to Afro-descendants and non-Indigenous people. Dem boundaries should get confirm by law, as di limits set fi Indigenous Territories cyaan change fi mek dem smaller except expressly by di law.

Di Afro-tribal community recognize an appreciate di state’s recognition an territorial expansion granted to Indigenous peoples. However, such expansions shoulda neva come at di expense of aneda Afro-tribal community, especially when di inclusion of dem territories a result from inaccurate measurements weh di state admit to. Di state’s reliance pon aerial surveys fail fi recognize di long-standing presence of di Afro-descendant community, weh deh bout fi centuries. Di community a stress di importance of equal respect an protection fi di ancestral rights of Afro-tribal communities; instead of issuing demolition orders an continuing fi move Afro-Caribbeans, wi a look fi peaceful solutions weh honor di historical an cultural significance of both communities, ensuring fair treatment an fostering a spirit of mutual respect an coexistence.

Despite di international obligations of di Costa Rican state weh forbid it from instituting measures, whether policies, legal norms, or administrative practices, weh mek tings worse or deteriorate di situation of Afro-descendants, it tek up a set a regressive measures such as officially repealing or suspending necessary legislation weh did allow Afro-descendants to keep enjoying di rights recognized inna those norms, like di right to property titling, legal security an guarantees against evictions.

Di Costa Rican state enact legislation an tek up policies weh clearly nah match up wid di existing national or international legal obligations regarding di rights recognized by Afro-descendants. To get really specific, fi example, Law 6043 of 1977, Resolutions of di Constitutional Chamber (vote 3113-09 annuls law 8464, vote 2375-17 annuls law 9205), an Provisions of di Comptroller General’s Office (to di Ministry of Environment and Energy, report # DFOE-AE-IF-04-2011, an to di Municipality of Talamanca).

Di Struggle fi Recognition an Rights

Di journey towards securing wi rights an recognition long an tough, marked by setbacks an milestones. Establishing di Afro-descendant Tribal Peoples Forum inna Costa Rica represent a beacon of hope, an acknowledgment of wi existence, an a platform fi advocate fi wi rights. Dis initiative, grounded inna di principles of ILO Convention 169 an supported by di Presidential Decree pon di Verification of Self-Recognition of Afro-descendant Tribal Peoples, mark a significant step forward inna wi quest fi justice an self-determination.

Wi engagement wid national an international forums nah just bout securing land rights; it bout asserting wi place inna di world, advocating fi wi cultural preservation, an challenging di narratives weh historically marginalize wi communities. Di struggle fi recognition extend beyond di legal battles fi land—it a fight fi di preservation of wi heritage, wi language, an wi traditions, weh link inextricably to di land we call home.

Di communities along di railroads weh wi build, an di communities of Barra del Colorado, Tortuguero, Guacimo, Siquirres, Matina, Limon, Cahuita, Puerto Viejo, Manzanillo an Sixaola, dem communities predominantly of African descent have witness firsthand di deep-seated issues of systemic discrimination an segregation weh plague wi communities fi generations. Wi lands, rich inna natural beauty an cultural heritage, a get tek weh by di state, a practice so normalized over di years seh nuff a wi start fi accept it as inevitable. Dis nah just bout losing pieces a land; it bout di erosion of wi identity an heritage.