The Cienfuegos Botanical Garden

Harvard’s Legacy, Cuba’s Challenge

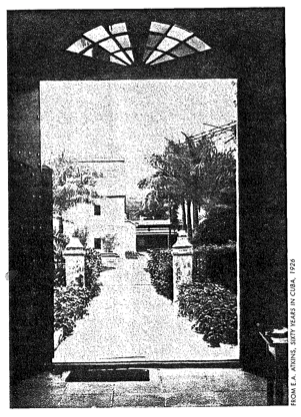

From door of the main house, Cienfuegos Botanical Garden, more than seventy years ago.

The Cienfuegos Botanical Garden, about three-quarters of an hour outside the Cuban city of Cienfuegos at the “Pepito Tey” sugar complex, welcomes visitors to a park-like setting of palms, orchids, bamboos, and myriad other tropical plants. The exotic vegetation; the shade, stream, and entry lane of royal palms; the reciprocally appreciative toasts of cane juice provoked by “official” visits-all stand in inviting contrast to the sugar mill’s neighboring clangor and sweat.

The enticements of this neotropical Garden of Eden, however, suggest questions as well as contentments. Why so splendid a facility, so far from the beaten track? How did the Garden come by its more than two thousand tropical species? What purpose does it serve? From whence the now-faded markers of a Harvard connection?

Our story finds its start in Boston and in Cienfuegos itself. Cuba was one of Spain’s first New World conquests. Cienfuegos, however, was only founded in 1819, after a lag of some 300 years. Sugar was by then the dominant cash crop and Yankee merchant firms, among them Boston’s “E. Atkins & Company,” were active in its exchange. Thus Edwin F. Atkins, the founder’s son, first visited the island in the 1860s in order to master the family trade and the connections upon which it was based. The exposure took, and Edwin gradually assumed complete control over the Cuban operation.

Atkins began his business life in a commercial world based on consignments and commissions. Sugar production, however, was already in flux. Mechanized refineries required heavy investments. Shifting tariffs, population movements and industrialization in the Northern hemisphere, and emerging product competition from both European beet sugar and Pacific sugarcane created an ever-changing structure of sources, prices, and markets.

Cuban planters also had to adjust to endemic civil unrest and the abolition of slavery. Many were unsuccessful. Atkins, despite strong misgivings, thus settled an intractable debt by taking over the “Soledad” sugar estate around 1880. The plunge once taken, he invested heavily in additional land and technological improvements. He wintered on the estate, often without his family, and forged one of the island’s most productive sugar complexes. The process was not without risk: banditry, brushes with armed bands allied to every possible faction, and repeated seasons of arson-damaged cane became almost commonplace as the island chafed under Spanish rule.

Atkins, who hoped that greater Cuban autonomy within the Spanish Empire would end the unrest, championed this outcome through his high-level connections in both Washington and Havana. He later on quickly accepted North American occupation as a portent of peace and stability. His thoughts almost as quickly turned to intensifying Soledad’s sugar production, with Harvard as one of the vehicles. In 1899, Atkins donated $2,500 to the University to compile a comprehensive bibliography on sugarcane and to fund a “traveling fellowship in economic botany,” whose recipient was expected to conduct research that would improve the island’s cane production.

By the turn of the century, Harvard’s annual reports regularly referred to the “Experimental Garden in Cuba” (soon relabeled the “Harvard Experiment Station in Cuba”). The Garden’s initial preoccupation was to grow sugar cane from seed rather than cuttings, a first step toward the larger goal of developing more productive and resistant strains. Other work addressed cane diseases and pests, and tropical food crops. Despite the Harvard label, during these early years Atkins provided all of the Garden’s land, labor, and funds. The main focus remained practical agriculture, though more and more specimen plants were collected as well.

The tax benefits of charitable donations, in tandem with his continuing satisfaction with the Harvard connection, in 1919 induced Atkins to arrange a long-term lease of land and to pledge an eventual endowment of $100,000-the “Atkins Fund for Tropical Research in Economic Botany”-for what became known as the “Atkins Institute for Tropical Research.” (As during its unofficial years, both the Garden’s designation and its precise institutional slot within the University remained rather loose.) The “Harvard House” for visiting researchers and students was built soon after, and aggressive programs to obtain more plant species were put into place. Atkins himself died in 1926, though both his widow and his son-in-law (who followed him as president of the Soledad Sugar Company) continued to support the Garden.

The decades following Atkins’s death saw programs at the Botanical Garden meander along a course defined by several overlapping tensions. Civil unrest remained endemic, though several decades of relative calm followed the revolutionary movement of 1933. Increasingly stringent labor laws mandated higher minimum wages, limitations on non-Cuban workers, and a 1933 reduction in the work week to but forty-eight hours. Ever-increasing costs became the norm. The Garden’s vulnerability to flood, drought, and hurricane reinforced the sense of contingency.

By the mid-1930s, the Garden routinely overspent the income from the Atkins endowment, despite repeated additional gifts from Mrs. Atkins and from the Claflins, her son-in-law’s family. Programmatic fuzziness exacerbated the financial tensions between Garden and gown. Was the Garden’s destiny to become a first-rate tropical arboretum? Or was its purpose to conduct original research? In the latter case, should its focus be practical or theoretical, or should it simply respond to requests as received?

The Botanical Garden in fact engaged in a variety of pursuits. Wartime appeals from Washington led to experiments with rubber trees. Research on tropical food crops reflected Edwin Atkins’s initial wish that the Garden, as one of its goals, address the island’s general welfare. Rare botanical specimens were exchanged with facilities all over the world. Tree saplings were cultivated for reforestation efforts at Soledad and neighboring estates, and landscaping plants were dispatched to the new U.S. base at Guantanamo Bay. By the 1950s, Harvard was using the Garden for summer courses in Tropical Botany. The Garden became a local tourist destination as well, provoking worried accounts of thirsty plant lovers’ needs for potable water and more general supervision.

The Castro Revolution, and the following downward spiral in U.S.-Cuban relations, provoked an extended hiatus in the Harvard connection. Operations were gradually reduced as of 1959. Expatriate staff members sought other jobs, and the University relocated three anti-Castro employees off the island. Direct financial support ceased as of September, 1961, and a straw-clutching skeleton office in Cambridge closed soon after. The Cuban government took over the facility, and has managed it ever since. New possibilities for collaborative teaching and research may now, after more than a generation, be on the horizon: the Harvard-Garden relationship may have life in it yet.

As in most good stories, that of the Cienfuegos Garden abounds in ambiguity and paradox. The principal actors-Edwin Atkins, Harvard University and the Cambridge-based scholars who administered the Garden, on-site superintendents and staff, Cuban officials and employees, the Soledad estate and its managers-operated with agendas that were sometimes complementary and sometimes at odds. The shifting backdrop of war and revolution, depression and prosperity, hurricane and drought, likewise wove a tapestry that this sketch can only begin to describe.

Cuba then: Left. Employee’s houses- Harvard House in distance; Right: Loading Cane

The Botanical Garden’s story also resonates with matters very much on our minds today. Issues of contributions and control, of motivations and authority, surfaced throughout its history. Is the Garden’s past merely the tale of a Boston plutocrat who successfully co-opted the University on behalf of his bottom line? Through what formal mechanisms and interstitital arrangements were the Garden’s programs and activities established? What of the byplay between the University’s distant administrators and the founder-cum-benefactor’s intimate proximity? The scientific and ecological issues were no less complex. Could the Garden be coherent as its projects by turn pursued better sugar cane, improved food crops, reforestation, and the largest possible collection of tropical plants? Were these activities even compatible with one another? Finally, what of the Garden’s political and social impact? Harvard’s enclave within Cuba can be perceived in any number of ways. The Garden was highly responsive to requests from Soledad Sugar and from the American government. It also conformed to Cuban law and attempted an at least limited engagement with Cuban needs. At a homelier level, the Garden’s administrators, researchers, and professional staff were overwhelmingly white, male, and expatriate. Cubans were most visibly present as laborers, many descended from slaves. The interplay of race, class, and nationality, while unremarked, was inescapable.

These are the sorts of unanswered and perhaps unanswerable questions most satisfyingly pondered in Cienfuegos, at the joint venture tourist hotel which bills in dollars for lodging in its fenced compound overlooking the bay, and whose daily busloads of European visitors are hailed with free drinks and minimally-clad dancing girls. In the evening, adventuresome tourists can stop by one of the neighboring bars for drinks and to strike up friendships with the many young women questing for cash. In the meantime, construction is about to resume at the once-abandoned, half-built, Chernobyl-style nuclear power plant that looms in the distance: finally, locals rejoice, the area’s daily blackouts will come to an end.

Contemporary Cuba is a vortex of paradox. Ecology vies with economics, revolution with reality, ideology with iconoclasm, dependence with development. The puzzles are much the same as those posed by the Botanical Garden. Rather than simply a historic curiosity, the Garden thus partakes of issues that are both continuing and crucial. Like so much in today’s Cuba, it is emblematic as well as idiosyncratic.

Fall 1998

Dan Hazen, Widener Library’s “Librarian for Latin America, Spain, and Portugal,” visited Cienfuegos for an international conference of historians and archivists in March 1998. He has been at Harvard for about nine years, after holding similar posts in the Latin American collections at Cornell, Stanford, and Berkeley.

Related Articles

Caballero wins Colombia’s top journalism prize

Building on work she started at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, investigative journalist Maria Cristina Caballero has won Colombia’s top journalism prize…

Between Vengeance and Forgiveness

At the close of this century of death camps, killings fields and desaparecidos, there is perhaps no more urgent question than the one raised in Martha Minow’s useful new book: Can societies…

The Environment in Latin America

This issue of the DRCLAS NEWS deals with some of the environmental problems of Latin America, one of the priorities of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies…