The Cocalero Social Movement of the Amazon Region of Colombia

The Quest for Citizenship Rights

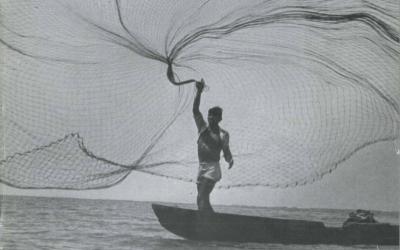

Cocaleros protestors in Putumayo. Photo courtesy of María Clemencia Ramírez.

More than 200,000 peasants, including women, children and indigenous people, marched from their farms to the nearest towns and government seats to protest a threat to their principal source of income. The marches continued for three solid months. That was 1996, and the crops these farmers were growing was coca, the plant used to make coca paste—the basis for cocaine. The protests were the spark that ignited the cocalero social movement, a civil society effort to overcome the marginalization of these peasants.

The United States had just decertified the Colombian government from receiving further U.S. aid because the counter-narcotic efforts of the Latin American country did not meet U.S. standards. The Colombian government responded by increasing aerial spraying of coca plantations in the Amazon region and exerting more control over the sale of gray cement and gasoline, used for processing coca into coca paste. This increased enforcement of laws against illicit drug cultivation and processing set off an uprising among coca growers and harvesters (cocaleros) in the departments (states) of Putumayo, Caquetá, Guaviare, and the Baja Bota region of the Cauca department in the Colombian Amazon.

The cocalero social movement was a response to state policies. Its intention was to expose the social and economic reality of the small coca growers in Amazonia and demand recognition as social actors. It can be said that in Colombia, the state has excluded its citizens by maintaining the long-term structural marginality of Amazonia. Social movements respond to this exclusion by demanding inclusion through a concertación, a coordinated effort with government agencies to meet their needs for the provision of certain basic services. In negotiations, while being supported by the civic strike, movement leaders confronted the power of the state and compelled its representatives to hear them and take their perspectives into account. The result was a mutual agreement.

THE STATE IN THE AMAZON REGION AND CIVIL SOCIETY

In this area of armed conflict, the civil state is looked upon as the institution that can support alternatives to the conflict. The paradox is that cocaleros have gained the state’s attention only because of the increasing expansion of the coca economy. Stigmatized as guerrilla auxiliaries and criminals, cocaleros began demanding political recognition and increased participation in decision making. In other words, state-fostered repression and marginalization has created a strong civic movement that demands state protection and economic aid.

Although the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) has supplanted state authority in the case of the Amazon region,, official institutions are still working in the area. Peasants demand that these institutions develop economic and social programs for their benefit. Moreover, local authorities, such as mayors and personeros (municipal attorneys), are perceived as allies in the peasants’ fight to gain recognition as political and social actors.

The internal divisions among state functionaries in the local, regional and national levels were highlighted by thecocaleros social movement: while the central government characterized the movement as “guerrilla-instigated,” the mayor of Puerto Asís (Putumayo) declared to the media that the strike was not supported by the guerrillas and asked the government not to continue the aerial sprayings with herbicides because coca-growing needed to be recognized as the peasant’s main income. The mayor assured that the strike was organized by the Communal Action Councils (Juntas de Accion Comunal) and peasant leaders, and denied of the guerrillas’ involvement (El Tiempo, July 29, 1996). It was clear that the guerrillas participated in the organization of the cocaleros‘ marches, supporting the social, economic and hence, political vindication of the peasants. The guerrillas took advantage of the delegitimization of the state resulting from its failure to fulfill the agreements with the peasants, as well as the violence and repression that was exercised by the military against the social movement.

It is important to examine how the state is perceived, represented, and interpreted from below, by the people under its rule, as well as how it constitutes political reality and produces concrete effects. Everyday practices and specific historical and cultural situations become crucial to achieving an understanding of how the state is constructed locally. In the Amazon region, the FARC has played an important role in constructing the way people perceive the state, and within this theoretical framework, FARC’s discourse can be seen as part of this local complexity. The FARC supported the cocaleros’ social movement, making it possible for their strike to last for months and enabling the peasants to negotiate with the central government from a strong position. Although the FARC assumes disciplinary functions among the population, it is not replacing the state in this respect. The state is expected and demanded to carry out its constitutional obligations in the area, both by the FARC and the inhabitants of the Amazon region. The FARC oversees the mayor’s office, supervising city revenues and payments, and municipal employments. Moreover, the FARC is promoting the exercise of citizens’ rights in these places, arguing that increased participation results in increased local power. FARC’s support of, rather than suppression of, local participatory power politics merits careful analysis. However, as FARC’s discourse, which conveys the need to construct participatory democracy, is, in most cases, not backed up by specific actions, such as socio-economic plans for the people, political violence continues to be the status quo. Guerrilla authoritarianism of course, is antithetical to democratic participation. In October of 1997, FARC did not permit elections for mayors and governors to take place in some towns. This action produced strong enough opposition to lead to elections (although with a poor turnout) in spite of FARC’s order, with some popular candidates being elected. In other towns, the FARC’s candidates were elected. In some cases, popularly elected independent candidates were later forced to renounce office and were replaced by those appointed by the guerrilla group.

After the cocaleros’ social movement and in response to the political and territorial power of the guerrillas, paramilitaries increased their presence in the Putumayo, Caquetá and Guaviare departments beginning in 1998. As a consequence, the number of confrontations with the FARC increased, along with the number of instances where peasants were caught in the crossfire. The leaders of the cocaleros movement were accused of being guerrillas and their lives were threatened to the point where they had to disappear from the political scene. During January and February of 1998, paramilitaries killed 38 suspected guerrilla supporters in Puerto Asís alone. The mayor accused the army of providing helicopter support for the paramilitaries. As a result, citizens of the Putumayo began denouncing the suspected coalition between paramilitaries and the army, as well as the “black lists” that contained names of citizens to be killed because they were suspected of being guerrilla supporters. In an area where guerrilla groups have been supplanting the rule of the state since 1984, it is very easy to be considered a guerrilla collaborator.

In June of 1998, 500 peasant leaders from the Putumayo went to see then-President Ernesto Samper in Bogotá to condemn the serious level of human rights abuse in the Putumayo due to the presence of paramilitaries acting with the complicity of the Army. Citizens of the Putumayo, organized into a Committee for the Defense of Life, asked Samper to protect their lives and to set up an international tribunal. Moreover, peasant leaders cautioned that if the state did not take prompt action on this issue, they would be forced to arm themselves in self-defense. Meanwhile, the massacres of peasants accused of being guerrilla supporters continued—for example, in January 1999, 28 peasants were killed by paramilitaries in El Tigre, Putumayo, and 20 were killed in Zabaleta, Caquetá, on March 9, 1999.

It is clear that in the case of Colombia, the power and terror exercised by paramilitary and guerrilla groups in the coca growing areas necessitates the strengthening of civil society in order to confront these armed authoritarian actors. Although Colombia has not experienced a dictatorship, the long-term armed conflict has forced civil society to organize and make itself visible. It has been pointed out that in the Amazon region, the paramilitary organizations are acting with the support and acquiescence of the Armed Forces, as many local residents have testified. One movement leader characterized this situation as a “national policy of state terror” (Intervención en la toma de la Defensoría del Pueblo, 1998). Human Rights Watch, in a February 2000 report, presented evidence of close ties between the Colombian Army and paramilitary groups. Paradoxically, while the Armed Forces were promoting violence, the civil government was conducting peace negotiations. In this context, civil society cannot be conceived as opposition to an evil state. In contrast, continuity between the state and civil society has to be encouraged for the sake of the Amazon region. The armed conflict has blurred the boundaries between civil society and the state., and the assumption that achieving a strong civil society requires autonomy from the state has to be reconsidered. Thus, how the “authoritarian” is transformed into the “political” through collective action becomes a central issue in the social movements emerging in this conflict area.

It can be expected that in the Amazon region, where illegal activities have become the rule of law, if the state continues repressive action through an ill-conceived “drug war”, the civilians will be forced to take sides by joining either military, paramilitary or guerrilla groups. Paradoxically, the result is less state authority, an empowered insurrectionist movement, an increasingly armed citizenry, escalating violence, and a decrease in public spaces within which to build a civil society and reestablish links to the state.

TOWARDS PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRACY AND STRENGTHENING OF CIVIL SOCIETY AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO CIVIL WAR

In this war context, it is necessary to examine the kinds of local-state articulation that results in either increased or decreased political space, permitting or preventing the development of participatory democratic institutions.

I contend that in the Amazon region, collective identities are shaped by the sense of exclusion and abandonment by the state, and in this context the act of exercising citizenry has a cultural meaning that has to be examined. It was evident during the 1996 marches that being defined as a colono (settler) and/or a cocalero (coca grower) became an exclusive category. It meant not only to be considered as migrants with no regional identity and/or delinquents, but also to be pinpointed as people to whom the central state does not ascribe a place within society and as such, can be objects of state violence. As a consequence, the construction of a new citizenship becomes central for these social movements, which emerge independently from the traditional political parties, and which demand participation in local state policies and development plans. Thus, the introduction of negotiation procedures (i.e. negotiation tables between official representatives and leaders of the cocaleros’ movement) as a means to collectively participate in decision-making clearly was a main catalyst in turning the cocaleros movement into a social and political movement.

Through the cocaleros social movement, peasants of the Amazon region achieved collective empowerment. As a group, they were able to generate policy proposals that sought to both gain veto power over policies that affected them as a recognized differentiated group (colonos campesinos and/or campesinos cocaleros) and guaranteed that public officials would respond to their concerns once agreements were signed. Thus, leaders of the cocaleros’ social movement were seeking social justice through the exercise of participatory democracy.

The 1991 Colombian Constitution opened spaces of democratic participation that the inhabitants of the Amazon region have since used in order to exercise citizen rights and participate in the process of democratization in what has been a traditionally hegemonic and actively exclusive state. Such was the case of the tutela action that the Personero Municipal of San Jose del Fragua instituted against the Armed Forces in Caquetá during the 1996 social movement. In Puerto Asis (Putumayo), cabildos abiertos (open councils) to promote peace and oversee local government administration have been organized since 1997; they allow civil society to propose alternatives to the armed conflict or to demand that the central government support local civil organizations’ alternative economic initiatives to coca cultivation. As Michael Walzer has claimed, “To call the state to the rescue of civil society” is a central issue in the context of the Colombian armed conflict between guerrilla groups, paramilitary organizations and the military.

The cocaleros social movement illustrates not only how a new collective identity can be constructed under extreme adverse circumstances, but also how a new civil society can rise, paradoxically, from the ashes of rejection, stigmatization, criminalization, and scapegoating. The cocaleros demanded their right to be recognized and included as part of the nation of Colombian citizens, and are showing their will to enhance participatory democracy instead of aggression.

María Clemencia Ramírez is presently a senior researcher at the Colombian Institute of Anthropology and History in Colombia. She received her Ph.D. in Anthropology at Harvard University and has focused her anthropological research in the Amazon Region of Colombia in the department of Putumayo. The Spanish version of her dissertation Between the Guerrillas and the State: The Cocalero Movement, Citizenship and Identity in the Colombian Amazon was published in Colombia in December of 2001.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.

Editor’s Letter: Colombia

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American…

Photoessay: Shooting for Peace

Photoessay: Shooting for PeacePhotographs By The Children of The Shooting For Peace Project As this special issue of Revista highlights, Colombia’s degenerating predicament is a complex one, which needs to be looked at from new perspectives. Disparando Cámaras para la...