The Flowering of Culture in Santa Cruz

Diverse And Mestizo

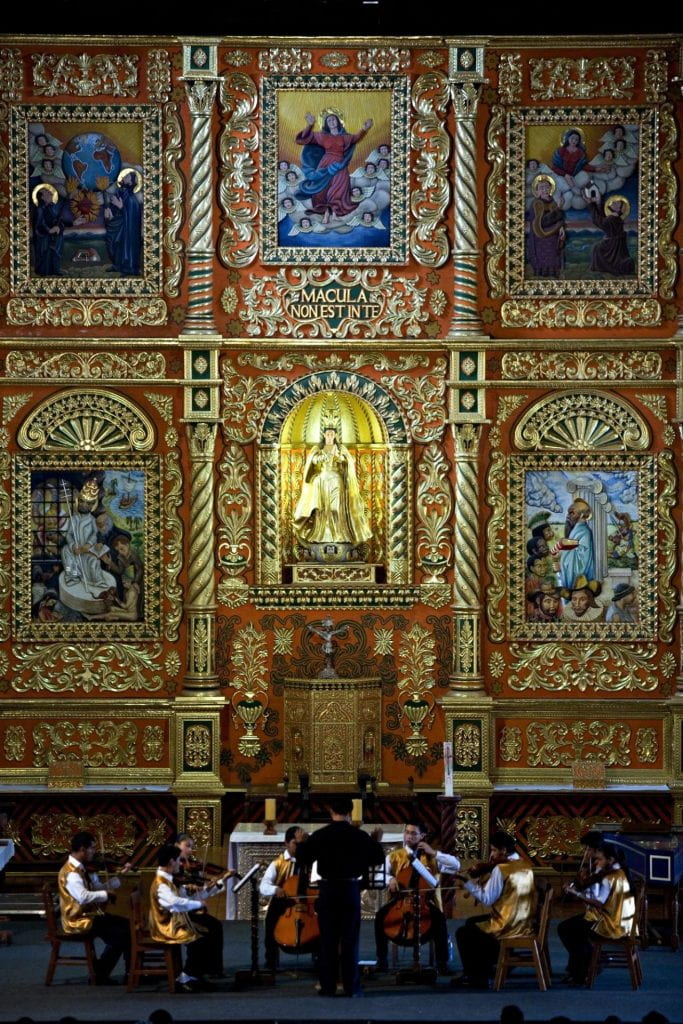

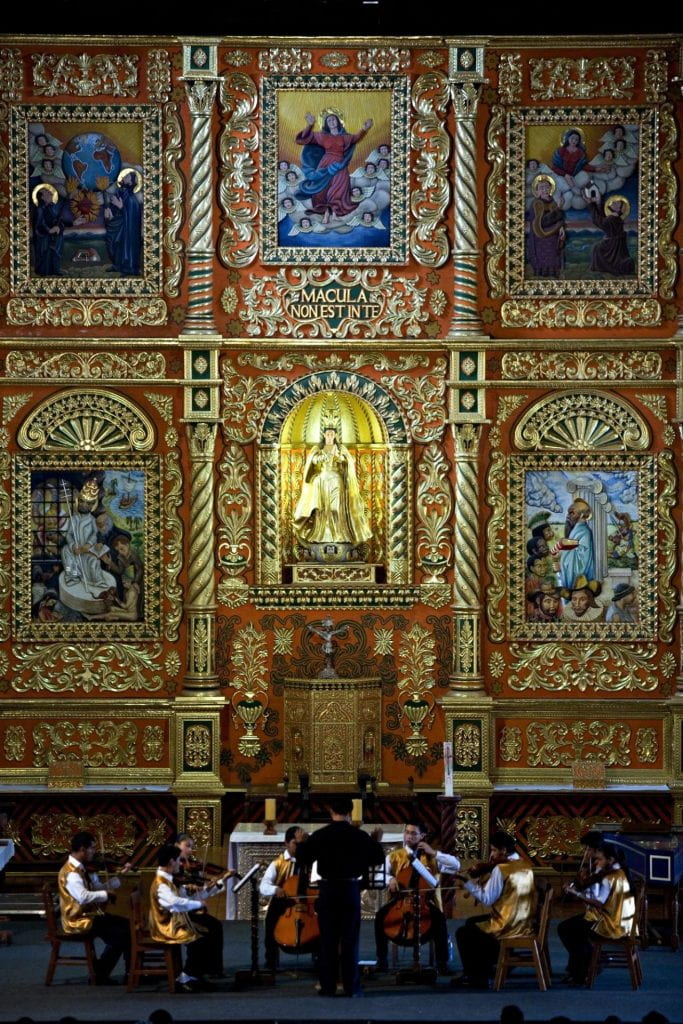

Santa Cruz hosts an early music festival in the colonial-era Jesuit Missions. Photo by Patricio Croocker/Apac

Strains of baroque music waft from San Javier, one of the many colonial-era Jesuit Missions in the Santa Cruz de la Sierra region. Musicians are practicing for the International Festival of Early Music, which attracts music lovers and tourists from around the world. What might surprise you is that much of this music was composed by Bolivians themselves. When the Catholic Church began restoring Jesuit churches attached to the old missions of the Chiquitos region in the 1970s, more than 5,000 sheets of sacred music scores were discovered, composed during the 17th and 18th centuries by both Europeans and residents of the zone. Until the mid-19th century, musicians in the towns routinely performed these pieces. Now, with the festival and the creation of music schools throughout the region, this tradition—drawing on the historic blending of Spanish and indigenous cultures—is being kept alive.

Bolivia is well known for its rich Andean cultures—the Quechua and Aymara, among others. Less known is that we have been capable of creating a mestizo culture that we can all identify with. The eruption of Chiquitos onto the stage of national history shows us that this culture, in spite of poverty and neglect, still thrives, and demonstrates that Bolivian culture is much more than Andean culture.

Against all predictions, Santa Cruz de la Sierra has not only become the economic capital of the country, but also its cultural capital. In addition to the Early Music Festival, the city hosts an international theater festival, a Latin American film festival and several other Bolivian cultural festivals.

This blossoming of culture goes against popular perceptions of Bolivia. When you think about Bolivia, you probably think about an Andean country with lots of indigenous people and an economy based on mining. However, many of those ideas are based on misconceptions.

Bolivia is much more than an Andean country. Some 70% of its territory is made up of flatlands that encompass the Amazon basin and the Chaco region with its forests and jungles.

With the violence and death of the Spanish Conquest, America as a whole and the present Bolivian territory in particular ceased to be indigenous and became mixed race, mestizo. All Bolivians can be viewed as cultural mestizos and most are also biological mestizos. However, in the past few years, some have sought to characterize Bolivia as “an Indian country, ruled by an Indian,” erasing in one fell swoop 500 years of history.

And in the mid-20th century, Bolivia stopped being an exclusively mining country and became an agricultural country, producing its own food.

Bolivia is a centralized country, which is by no means a novelty in our America. Since the creation of the republic in 1825, it has put into practice an Andean-centric policy that does not look beyond the mountains. That was true when the capital was in Sucre, and is just as true now that the government rules from La Paz.

This obliterating centralism has led to a dichotomy between the Andean and lowland regions, creating two visions of our country, which have in the last few years appeared to be irreconcilable.

As a result of this centralism, the history of the lowlands is a history of forgetting. Thus, Bolivia, which became a republic in 1825 with its base in the territory of the Royal Court of Charcas, was presented to the world in terms of stereotypes that are very hard to undo—both at home and abroad.

In the middle of the last century, thanks to studies by art historians, Bolivia began to take a hard look at itself in the mirror, learning through plastic arts and other art forms to discover another identity, that of the mestizo. Art historians here, for example, coined the term baroque mestizo to describe the Bolivian architectural style that had been incorporating elements of both indigenous art and Baroque architecture since the 17th century. Although at first we did not like what we saw in the mirror (the Europeanizers because there was too much Indian in the mix; the indigenists because there was too little), bit by bit we began getting used to this concept and admitting our cultural and biological mixed race heritage. We began to assume that identity and to be proud of it. However, as is the custom in this country, the focus was only on the Andean region; the lowlands continued to be ignored.

Also in the middle of the last century—in the 1940s—the mining industry fell into a crisis. The government contracted a North American consulting firm that determined, in a report known as the Bohan Plan, that mining had run its course and that if Bolivia wished to be economically viable, it had to shift its economy towards the lowlands. Thus began a new and important stage of national history. The great protagonist of this new stage, the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra—which had about 60,000 inhabitants at the time and today has more than a million and a half—became the rival of Andean politics, confronting deeprooted centralism to achieve the status of which it had been deprived for 400 years. In this process of making itself visible, Santa Cruz has not only fought to right regional grievances, but also has contributed to the national democratic process by spearheading the democratic election of mayors and prefects (governors) and seeking departmental (state) autonomy, a struggle that is still ongoing.

Santa Cruz de la Sierra has become prominent in national life, politically, economically and culturally. The city has created its own style that is completely different from Andean centralism. It tries to do things in a grassroots fashion, sharpening its wit and creativity. In the 1970s the cultural institution known as the House of Culture was set up as part of a local initiative. It operated in an autonomous fashion with local economic support, as well as some international help obtained through its board of directors. In just a little while, the House of Culture became one of the most important and active cultural institutions in the country. And that became the launching pad for the cultural development of the region.

At the end of that decade, the Catholic Church began the process of restoring the churches of the old Jesuit missions of Chiquitos in the department of Santa Cruz, until then completely off the radar of both Bolivians and foreigners. In this process, as mentioned above, it was discovered that the inhabitants of these old missions—known as chiquitanos—had preserved an enormous quantity of musical scores from the 17th to 19th centuries. Two academics from the community (full disclosure: I was one of them) prepared documentation for UNESCO to declare the mission towns of Chiquitos Cultural Patrimony of Humanity (up until then the only Bolivian site with this status was Potosí, which had achieved the title through the action of the central government). The dossier made the argument that the Jesuit missions were living towns—pueblos vivos—and that the people of the lowlands had a patrimony worthy of this status. In 1990, UNESCO included six of the Jesuit mission towns in the Patrimony of Humanity list.

But this was not enough for those of us who worked in cultural development. There had to be a way for the local community—and then the regional and national communities—to make this patrimony their own. A small group of people (in a grassroots effort knocking on every door for funding) launched on an adventure to create an International Festival of Early Music. The response was very positive and in just a short time the festival has become one of the most important of its kind in the world, with the special characteristic that it takes place simultaneously in many different sites; and music groups from five continents participate. The festival has situated the music of the Chiquitos region in the panorama of universal music; it has become an important cultural reference point that has managed to elevate the self-esteem of the region’s inhabitants; it has stimulated tourism and—through the music schools that have been created in the small towns—become an alternative source of employment for the region’s youth.

There is no need here for grotesque costumes or for violence. The lowlands of Bolivia have learned to adopt their mixed race heritage and to bask in their identity through a socio-cultural process in which European and indigenous people learn to see eye to eye without excluding the other. And the creation and recovery of culture has been a vital part of that process.

Santa Cruz hosts an early music festival in the colonial-era Jesuit Missions. Photo by Patricio Croocker/Apac

El florecimiento de la cultura en Santa Cruz

Bolivia diversa y mestiza

By Alcides Parejas Moreno

Bolivia es un país muy mal conocido y lo poco que de él se sabe está basado en clichés que lo único que hacen es distorsionar aún más su imagen. Veamos algunos ejemplos:

- Es mucho más que un país andino. El 70% de su territorio corresponde a la llanura que participa de la cuenca amazónica y la región chaqueña.

- A partir de la conquista española—con todo lo que trajo consigo de violencia y muerte—América en general y el actual territorio boliviano en particular, dejaron de ser indios para pasar a la categoría de mestizos (todos mestizos culturales y una buena parte, además, biológicos). Sin embargo, en los últimos años se ha vuelto a distorsionar la imagen del país, pues se la quiere presentar como un “país indio, gobernado por un indio”, borrando de un plumazo casi 500 años de historia.

- A mediados del siglo XX dejó de ser exclusivamente minero, para convertirse en un país agropecuario, que empezó a producir sus propios alimentos.

He empezado hablando de lo que no es, ahora trataré de mostrar lo que es:

- Es un país centralista (lo que no es una novedad para nuestra América) que desde la creación de la república (1825) ha practicado una política andinocentrista que no mira más allá de las montañas, primero desde Sucre y luego desde La Paz.

- Este centralismo secante ha llevado a una dicotomía, lo que ha dado como resultado dos visiones de país, que en estos últimos años pareciera que son irreconciliables.

- Como resultado de este centralismo, la historia de la llanura es la historia de un olvido.

Así, pues, Bolivia—que fue creada como república en 1825 en base al territorio de la Audiencia de Charcas—se muestra al mundo con estos estereotipos de los que es muy difícil deshacerse, tanto para propios como para extraños. A partir de mediados del siglo pasado y gracias a los estudios de historia del arte que se habían iniciado, Bolivia empezó a mirarse en el espejo y a descubrirse a través de lo mestizo (fue en Bolivia que se inventó eso del barroco mestizo), tanto en el arte tangible como en el intangible. Aunque al principio no nos gustó lo que vimos en el espejo (los europeizantes, porque había demasiadas cosas indias; los indigenistas, por lo contrario), poco a poco nos fuimos acostumbrando y empezamos a admitir nuestra mesticidad, a asumirla y a sentirnos orgullosos de ella. Sin embargo, como de costumbre en este país, sólo se estaba mirando lo andino; la llanura seguía siendo ignorada.

También a mediados del siglo pasado—más concretamente en los años 40—la minería había entrado en crisis. El gobierno contrató a una consultora norteamericana que determinó que la minería había terminado su ciclo y que si Bolivia quería ser viable debía volcarse hacia la llanura (Este informe es conocido como Plan Bohan). Así empezó una nueva e importante etapa de la historia nacional: la incorporación de la llanura. En esta nueva etapa la ciudad de Santa Cruz de la Sierra—que en ese momento tenía alrededor de 60.000 habitantes y hoy supera el millón y medio—se convirtió en la gran protagonista y al mismo tiempo en la rival de la política andina, pues se enfrentó al centralismo para conseguir lo que durante 400 años se le había negado. En este proceso de hacerse visible, Santa Cruz de la Sierra no sólo ha luchado por sus reivindicaciones regionales, sino que ha contribuido al proceso democrático al protagonizar hechos de gran trascendencia a nivel nacional, como cuando abanderó la elección democrática de alcaldes y prefectos (gobernadores) y la lucha por las autonomías departamentales (que es todavía una asignatura pendiente).

Contra todo pronóstico y contraviniendo todos los clichés en boga, Santa Cruz de la Sierra ha irrumpido en la vida nacional no sólo en lo económico, sino también en el cultural. Para ello la ciudad ha llevado a cabo este proceso con un estilo propio que difiere diametralmente del centralismo andinocentrista. Se trata de hacer las cosas desde abajo, aguzando el ingenio y la creatividad. En los 70 y como una iniciativa local, se creó una institución cultural (la Casa de la Cultura), que funcionaba en forma autónoma y que tenía apoyo económico local y el resto dependía de ayudas internacionales que conseguía su directorio. En poco tiempo la Casa de la Cultura se convirtió en la más importante y activa institución cultural del país. Fue el punto de arranque para el desarrollo cultural de la región.

A fines de esa década la Iglesia católica había empezado el proceso de restauración de las iglesias de las antiguas misiones jesuíticas de Chiquitos, en el departamento de Santa Cruz, hasta entonces ignoradas por propios y extraños. En este proceso se descubrió que los habitantes de estas antiguas misiones (los chiquitanos) habían guardado durante más de 200 años una enorme cantidad de partituras musicales de los siglos XVII, XVIII y XIX. Cuando una buena parte de las iglesias habían sido restauradas, dos académicos de la comunidad prepararon el dossier correspondiente para ser presentado a la UNESCO para la declaratoria de los pueblos de Chiquitos Patrimonio Cultural de la Humanidad (hasta ese momento sólo Potosí ostentaba este galardón, que había conseguido por la acción del gobierno central) con el argumento de que se trata de pueblos vivos y que los pueblos de la llanura tenían un patrimonio digno de este galardón. En 1990 la UNESCO inscribió seis pueblos en la lista de Patrimonio de la Humanidad.

Pero eso no era suficiente para los que trabajaban en el desarrollo cultural regional. Había que buscar la forma de que la comunidad local primero, regional y nacional después, se apropiara de este patrimonio. Para eso también un grupo reducido de personas (desde abajo y tocando todas las posibles fuentes de financiamiento) se lanzó a la aventura de crear un festival internacional de música antigua. La respuesta fue muy positiva y en poco tiempo este festival se ha consolidado como uno de los más importantes del mundo, con la característica casi única que es itinerante, pues se realiza en muchas sedes simultáneas en las que participan grupos de los cinco continentes. Este festival tiene otra característica que lo hace muy singular, pues además de situar la música chiquitana en el panorama de la historia universal, se ha convertido en un importante referente cultural que no sólo ha servido para la elevar la autoestima de todos estos pueblos, sino que ha servido para incentivar el turismo y—a través de las escuelas de música que se han creado en todos estos pueblos—en una alternativa de trabajo para los jóvenes.

A partir de la irrupción de Chiquitos en la historia nacional se desmoronan algunos clichés. Esta cultura que está viva y que ha sobrevivido a pesar de la pobreza y el olvido, nos muestra una Bolivia que es mucho más que las ricas y mejor conocidas culturas andinas (quechua y aimara, entre otras) y que, sobre todo desde la llanura, así como en el resto del país, hemos sido capaces de crear una cultura mestiza que nos identifica a todos.

Contra todo pronóstico Santa Cruz de la Sierra no sólo se ha convertido en la capital económica del país, sino también en la cultural, pues en ella se realizan el ya mencionado festival de música así como uno internacional de teatro, otro de cine a nivel iberoamericano y varios a nivel nacional.

Las tierras bajas de Bolivia han aprendido a asumir su mesticidad mirándose al espejo sin necesidad de recurrir a disfraces grotescos ni a la violencia, pues se trata de un proceso socio-cultural en el que también se aprende a ver al otro sin exclusiones.

Alcides Parejas Moreno is a Bolivian historian who has written more than thirty books, including works about the history of Santa Cruz, several textbooks and four novels. He has taught extensively at universities and schools in both La Paz and Santa Cruz de la Sierra. He is one of the founders of the International Music Festival “Misiones de Chiquitos,” the International Theatre Festival and the Association for the Promotion of Art and Culture (APAC).

Alcides Parejas Moreno es un historiador boliviano quien ha escrito más de treinta libros, incluyendo trabajos sobre la historia de Santa Cruz, varios libros de texto y cuatro novelas. Él ha enseñado extensamente en las universidades y las escuelas en ambos La Paz y Santa Cruz de la Sierra. Él es uno de los fundadores del Festival Internacional de Música “Misiones de Chiquitos”, el Festival Internacional de Teatro y la Asociación para la Promoción de Arte y Cultura (APAC).

Related Articles

A Review of Alberto Edwards: Profeta de la dictadura en Chile by Rafael Sagredo Baeza

Chile is often cited as a country of strong democratic traditions and institutions. They can be broken, however, as shown by the notorious civil-military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990). And yet, even a cursory view of the nation’s history shows persistent authoritarian tendencies.

A Review of Born in Blood and Fire

The fourth edition of Born in Blood and Fire is a concise yet comprehensive account of the intriguing history of Latin America and will be followed this year by a fifth edition.

A Review of El populismo en América Latina. La pieza que falta para comprender un fenómeno global

In 1946, during a campaign event in Argentina, then-candidate for president Juan Domingo Perón formulated a slogan, “Braden or Perón,” with which he could effectively discredit his opponents and position himself as a defender of national dignity against a foreign power.