The Flowering of Culture in Santa Cruz (English version)

Diverse And Mestizo

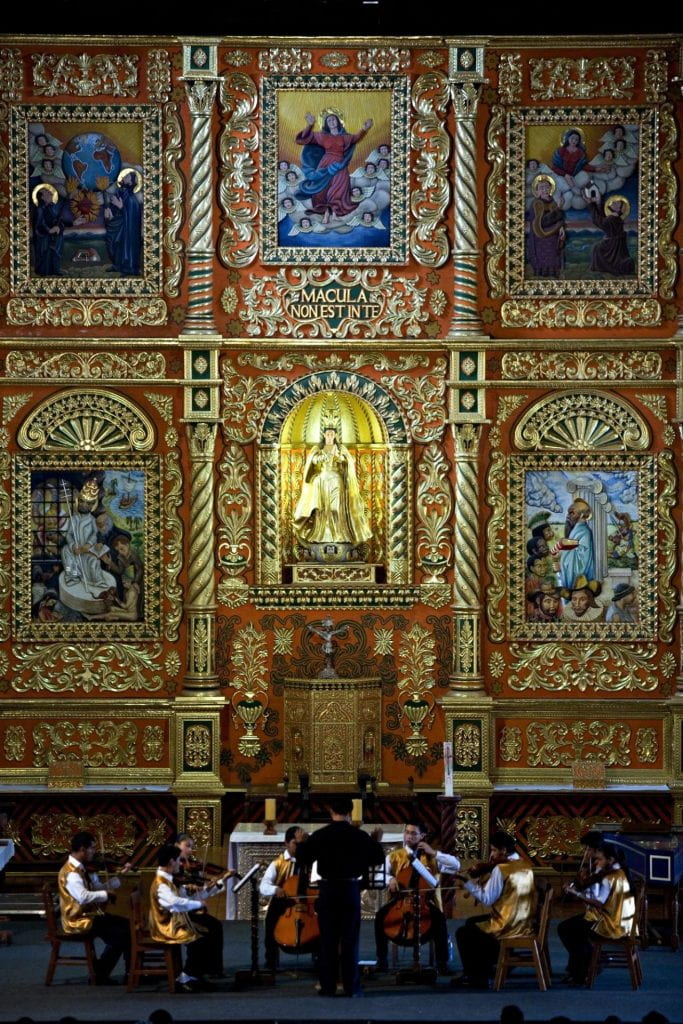

Santa Cruz hosts an early music festival in the colonial-era Jesuit Missions. Photo by Patricio Croocker/Apac

Strains of baroque music waft from San Javier, one of the many colonial-era Jesuit Missions in the Santa Cruz de la Sierra region. Musicians are practicing for the International Festival of Early Music, which attracts music lovers and tourists from around the world. What might surprise you is that much of this music was composed by Bolivians themselves. When the Catholic Church began restoring Jesuit churches attached to the old missions of the Chiquitos region in the 1970s, more than 5,000 sheets of sacred music scores were discovered, composed during the 17th and 18th centuries by both Europeans and residents of the zone. Until the mid-19th century, musicians in the towns routinely performed these pieces. Now, with the festival and the creation of music schools throughout the region, this tradition—drawing on the historic blending of Spanish and indigenous cultures—is being kept alive.

Bolivia is well known for its rich Andean cultures—the Quechua and Aymara, among others. Less known is that we have been capable of creating a mestizo culture that we can all identify with. The eruption of Chiquitos onto the stage of national history shows us that this culture, in spite of poverty and neglect, still thrives, and demonstrates that Bolivian culture is much more than Andean culture.

Against all predictions, Santa Cruz de la Sierra has not only become the economic capital of the country, but also its cultural capital. In addition to the Early Music Festival, the city hosts an international theater festival, a Latin American film festival and several other Bolivian cultural festivals.

This blossoming of culture goes against popular perceptions of Bolivia. When you think about Bolivia, you probably think about an Andean country with lots of indigenous people and an economy based on mining. However, many of those ideas are based on misconceptions.

Bolivia is much more than an Andean country. Some 70% of its territory is made up of flatlands that encompass the Amazon basin and the Chaco region with its forests and jungles.

With the violence and death of the Spanish Conquest, America as a whole and the present Bolivian territory in particular ceased to be indigenous and became mixed race, mestizo. All Bolivians can be viewed as cultural mestizos and most are also biological mestizos. However, in the past few years, some have sought to characterize Bolivia as “an Indian country, ruled by an Indian,” erasing in one fell swoop 500 years of history.

And in the mid-20th century, Bolivia stopped being an exclusively mining country and became an agricultural country, producing its own food.

Bolivia is a centralized country, which is by no means a novelty in our America. Since the creation of the republic in 1825, it has put into practice an Andean-centric policy that does not look beyond the mountains. That was true when the capital was in Sucre, and is just as true now that the government rules from La Paz.

This obliterating centralism has led to a dichotomy between the Andean and lowland regions, creating two visions of our country, which have in the last few years appeared to be irreconcilable.

As a result of this centralism, the history of the lowlands is a history of forgetting. Thus, Bolivia, which became a republic in 1825 with its base in the territory of the Royal Court of Charcas, was presented to the world in terms of stereotypes that are very hard to undo—both at home and abroad.

In the middle of the last century, thanks to studies by art historians, Bolivia began to take a hard look at itself in the mirror, learning through plastic arts and other art forms to discover another identity, that of the mestizo. Art historians here, for example, coined the term baroque mestizo to describe the Bolivian architectural style that had been incorporating elements of both indigenous art and Baroque architecture since the 17th century. Although at first we did not like what we saw in the mirror (the Europeanizers because there was too much Indian in the mix; the indigenists because there was too little), bit by bit we began getting used to this concept and admitting our cultural and biological mixed race heritage. We began to assume that identity and to be proud of it. However, as is the custom in this country, the focus was only on the Andean region; the lowlands continued to be ignored.

Also in the middle of the last century—in the 1940s—the mining industry fell into a crisis. The government contracted a North American consulting firm that determined, in a report known as the Bohan Plan, that mining had run its course and that if Bolivia wished to be economically viable, it had to shift its economy towards the lowlands. Thus began a new and important stage of national history. The great protagonist of this new stage, the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra—which had about 60,000 inhabitants at the time and today has more than a million and a half—became the rival of Andean politics, confronting deeprooted centralism to achieve the status of which it had been deprived for 400 years. In this process of making itself visible, Santa Cruz has not only fought to right regional grievances, but also has contributed to the national democratic process by spearheading the democratic election of mayors and prefects (governors) and seeking departmental (state) autonomy, a struggle that is still ongoing.

Santa Cruz de la Sierra has become prominent in national life, politically, economically and culturally. The city has created its own style that is completely different from Andean centralism. It tries to do things in a grassroots fashion, sharpening its wit and creativity. In the 1970s the cultural institution known as the House of Culture was set up as part of a local initiative. It operated in an autonomous fashion with local economic support, as well as some international help obtained through its board of directors. In just a little while, the House of Culture became one of the most important and active cultural institutions in the country. And that became the launching pad for the cultural development of the region.

At the end of that decade, the Catholic Church began the process of restoring the churches of the old Jesuit missions of Chiquitos in the department of Santa Cruz, until then completely off the radar of both Bolivians and foreigners. In this process, as mentioned above, it was discovered that the inhabitants of these old missions—known as chiquitanos—had preserved an enormous quantity of musical scores from the 17th to 19th centuries. Two academics from the community (full disclosure: I was one of them) prepared documentation for UNESCO to declare the mission towns of Chiquitos Cultural Patrimony of Humanity (up until then the only Bolivian site with this status was Potosí, which had achieved the title through the action of the central government). The dossier made the argument that the Jesuit missions were living towns—pueblos vivos—and that the people of the lowlands had a patrimony worthy of this status. In 1990, UNESCO included six of the Jesuit mission towns in the Patrimony of Humanity list.

But this was not enough for those of us who worked in cultural development. There had to be a way for the local community—and then the regional and national communities—to make this patrimony their own. A small group of people (in a grassroots effort knocking on every door for funding) launched on an adventure to create an International Festival of Early Music. The response was very positive and in just a short time the festival has become one of the most important of its kind in the world, with the special characteristic that it takes place simultaneously in many different sites; and music groups from five continents participate. The festival has situated the music of the Chiquitos region in the panorama of universal music; it has become an important cultural reference point that has managed to elevate the self-esteem of the region’s inhabitants; it has stimulated tourism and—through the music schools that have been created in the small towns—become an alternative source of employment for the region’s youth.

There is no need here for grotesque costumes or for violence. The lowlands of Bolivia have learned to adopt their mixed race heritage and to bask in their identity through a socio-cultural process in which European and indigenous people learn to see eye to eye without excluding the other. And the creation and recovery of culture has been a vital part of that process.

Alcides Parejas Moreno is a Bolivian historian who has written more than thirty books, including works about the history of Santa Cruz, several textbooks and four novels. He has taught extensively at universities and schools in both La Paz and Santa Cruz de la Sierra. He is one of the founders of the International Music Festival “Misiones de Chiquitos,” the International Theatre Festival and the Association for the Promotion of Art and Culture (APAC).

Related Articles

A Review of Aaron Copland in Latin America: Music and Cultural Politics

In Aaron Copland in Latin America: Music and Cultural Politics, Carol Hess provides a nuanced exploration of the Brooklyn-born composer and conductor Aaron Copland (1900–1990), who served as a cultural diplomat in Latin America during multiple tours.

Microfinance

When I first saw the photos of the sacking of BancoSol, I cried. The slide show began with chaotic pictures of the mob hauling desks, computers and files into the street and setting them on fire. Next were two captured looters lying face down and handcuffed amid the wreckage of what hours before had been a functioning bank branch. Finally, next-day photographs documented the ravaged premises of BansoSol’s branches …

Vivian Fernández: Student Perspective

This year, on August 2, Bolivia will commemorate the 80th anniversary of the founding of the escuela-ayllu of Warisata, an extraordinary intercultural experiment in indigenous schooling that flourished between 1931 and 1940 on the high plateau (altiplano) in the shadows of the volcanic peak of Illampu. On that day, the usual civic rituals and official remembrances—school pageants, TV documentaries, and editorial page …