The Food of the Gods

Feeding the Earth

This is a traditional-style painting from the town of Sahua, Ayacucho. The scene represents the banquet of the mountains that surround the town. The central figure is the mountain called Mariano Borao that protects the community, and the other figures are neighboring mountains or apus. Painting by La Asociación de los Pintores de Sarhua, courtesy of Luis Millones.

At the beginning of the 1990s, I traveled frequently to Osaka. Researchers from the National Ethnographic Museum of Japan were studying the Peruvian highlands, particularly Ayacucho, a state with a long and fraught history. Membership in this investigative team and my status as visiting professor opened the doors for me to a society that exhibited its charms on a daily basis. In the course of my stay, I discovered that one of my colleagues had an important relationship with the priesthood of the Church of Tenrikyo. I was interested in his religion and what I learned about it made me want to participate in the annual pilgrimage of its believers to the sacred city of Tenri, in the prefecture of Nara, in the Kansai region. For a short period, Tenri had been the capital of the Japanese empire (488-498), and still is today a beautiful city and religious headquarters of Tenrikyo.

The pilgrimage was tough and fascinating; of the many things I learned in those days, it is interesting to recall the answer to the question I asked about what food was eaten in paradise or its equivalent in the Christian dogma. I was totally surprised to learn that this equivalent, “Youkigurashi,” was a space similar to that of punishment: a great banquet, with the same food in both places. Both the condemned and the blessed had to eat with oversized chopsticks, and those who were punished for their bad behavior in life looked emaciated and hungry, while those awarded for good behavior in life appeared extremely pleased and well nourished. The explanation was simple in the context of a faith that practiced and emphasized solidarity: while each of the condemned tried to eat with the huge chopsticks and was unable to do so, those favored by divinity used the length of the instruments to feed each other.

Upon my return to Ayacucho, I took the same question on my field research, remembering that in Huamanga—the original name for Ayacucho—I would be as far from European occidental thinking as I had been in Tenri, when the priests danced in the underground spaces of the temple to renew the creation of the universe.

I knew the writings of the Spanish or the Christianized indigenous chroniclers in the late 16th and 17th centuries. These sources agreed that the Andean gods ate mullu, that is to say spiny oysters (Spondylus), and indeed our only source in Quechua reminds us that the sound made while chewing this shellfish was “cap! cap!” grinding their teeth while they ate (Ávila, Francisco de. 2007. Dioses y hombres de Huarochirí. Lima: Universidad Antonio Ruiz de Montoya).

Today, seashells still have religious prestige, even the plainer ones; they are used in ceremonies as a recipient to absorb through the nose the juice of hallucinogenic plants in other regions of Peru. But in Ayacucho, Cuzco and throughout most of the Peruvian highlands, feeding the gods is a complicated business.

In the first place, it should be noted that Christian evangelization destroyed all visible images of the Pre-Columbian religions. The sacred geography remained unharmed: the cult of the earth and its visible expressions, the mountains. To these we add the areas of contact with human beings: caves sand springs. While it would have been impossible to wipe out this last form of religiosity, the persecution also stopped because indigenous forced labor was a source of wealth for the Spanish Empire and all harassment of their work affected their productivity. In the 18th century, Andean society had already consolidated a religious structure that reinterpreted the Christian doctrine and blended it with pre-Columbian memories. That is the seed of the indigenous religion as we know it today. In that belief, the gods, that is, Mother Earth and the mountains (apus or wamanis), should receive food from their many worshipers. The food is sent through a ceremony with primordial roots that has at least two names in Quechua-influenced Spanish: pagapu and despacha: paga (pays, in Spanish) means to make payment to Mother Earth, and despacha (sends off, in Spanish) means to dispatch what she needs. If the one who offers is Quechua-speaking, he will use prayerful variations such as apachiku, mallichi and kutichi related to the makeup of the offerings and the place they are offered. These relate to the particular concerns of the person or persons who are feeding Mama Pacha, as Mother Earth is affectionately known. Thus, there are pagapus specific to cattlemen, to those who need rain or heavy river volume, to hunters. to people who need to recover their health, and many other motivations.

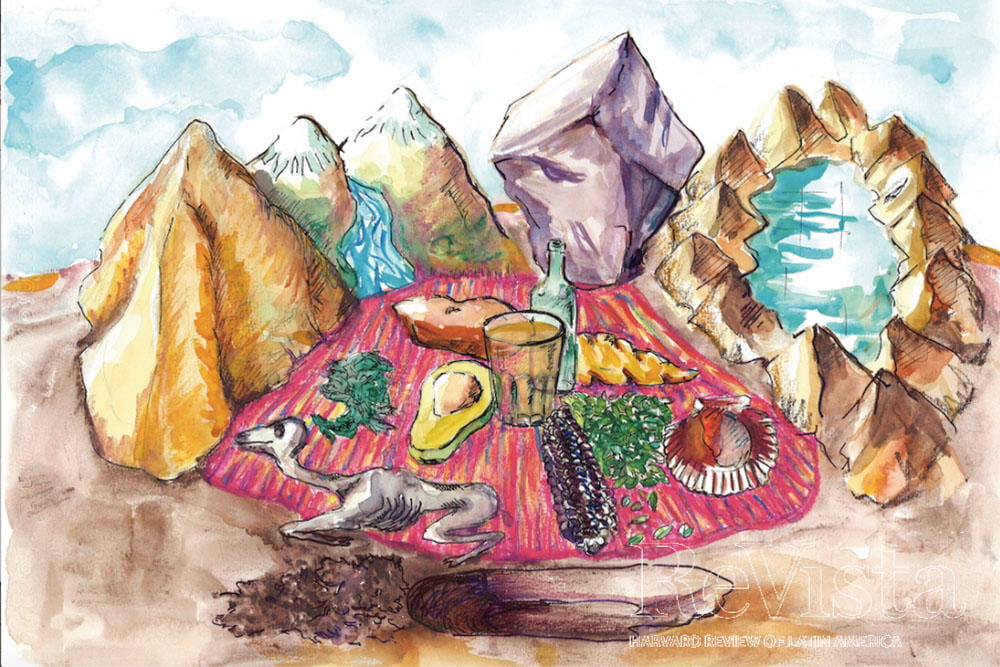

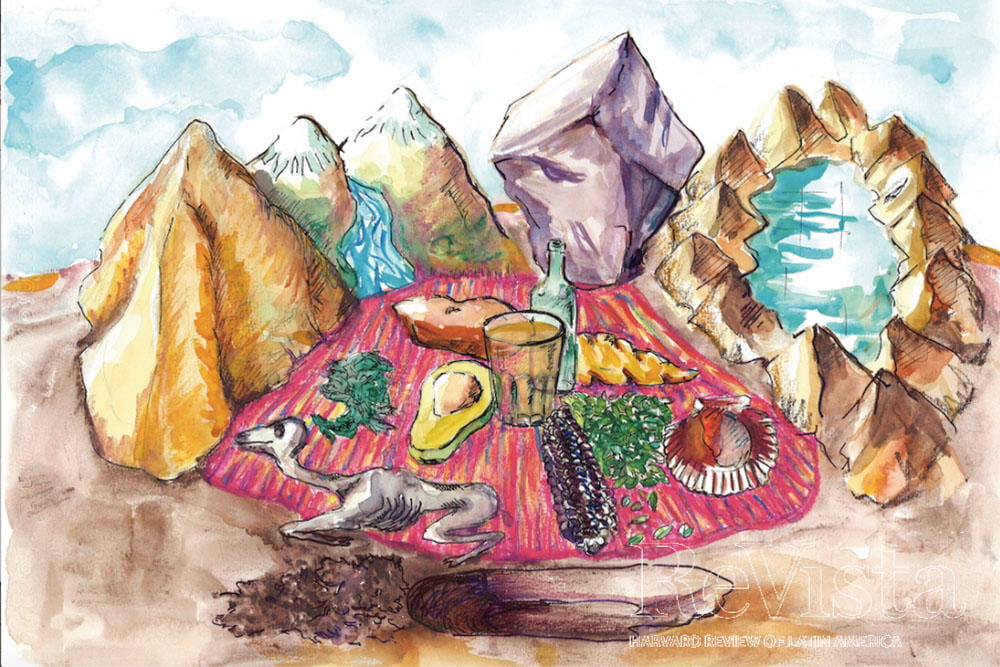

This image illustrates a gathering of the Andean gods in a ceremony of thankful payment to Mother Earth. The gods of the mountains, rivers, rocks and lakes are enjoying their foods-llama fetus, potato, sweet potato, another type of Andean tuber known as oca, scallops, algae, coca leaves, as well as imbibing wine and fermented homemade alcoholic beverage known as chicha. This is the offering known as papagu that the gods receive from humans in thanks for their blessing in providing the good annual harvest. Art by Rocío Rodrigo, courtesy of Luis Millones.

Many forms exist of preparing a pagapu, but one of the most important is the act of feeding Mama Pacha or Madre Tierra, to assure her generosity in permitting good harvests. Here I will let don Juan Quispe Andia, from Chungui, La Mar, Ayacucho, tell us about how to perform pagapu:

“On the heights of Chungui, when we are going to harvest potatoes, the owner invites all the neighbors to help, we are all going to help because it is the [indigenous] law; we all always help. In exchange for this help, the owner gives the neighbors food, coca leaf, hard drink [a home-made alcoholic drink brewed with anise, traditional plants and sugar]. When another peasant [who is not a neighbor] has to harvest, he must be paid for the help he gives. Because of this, no one holds back from helping. The neighbors come with all their family; the men do the harvesting, the women with their pallapadoras (harvest helpers) and cooks; the kids help to move the potatoes and stack them. The neighbors harvest, all the time joking, sometimes with music and sometimes not, always happy, having a great time and rejoicing in the fruits of the earth. When the harvest is over, the potatoes are stored in the owner’s house, but first the potatoes that are going to serve as seed for the next harvest are chosen, and also the potatoes that have been damaged by the hoes. The men watch over the potatoes and the seeds, while the slightly damaged potatoes are cooked with chile and salt, sometimes with meat or some stew that the owner’s wife has prepared. Everything is served along with chicha [an indigenous corn-based drink] and abundant liquor. Then people sit around chewing coca leaf [Erithroxylum coca] and drinking. The coca leaf maintains its sacred character, but it also invigorates its users. Finally, everyone leaves except for the owner’s compadre—the godfather to one of his children. They return to the farm alone, bringing with them the best potatoes, the most beautiful ones, to make the ‘payment’ to the earth so it will keep protecting them. The compadre makes a hole in a corner of the field, some 50 to 60 centimeters deep, and when he has made the hole, he sprinkles it with liquor from a small cup in the form of a cross and later he makes the offering of the potatoes, along with the liquor, usually a handful of kinto coca leaf, a couple of cigarettes, and then he closes up the hole, saying: ‘Mother Earth, receive the offer of your children to thank you for the harvest that my compadre has collected and to ask that you keep on giving us good production, for this we pay you, for the abundance that you give us.’ Later they return home and the owner invites his compadre to drink and eat. But during the ritual of the “payment,” the owner keeps silent; the compadre is the one who speaks as intermediary so that the earth will accept the offerings” (Delgado Sumar, Hugo E. 1984. Ideología andina: El pagapu en Ayacucho. Ayacucho: Universidad Nacional de San Cristóbal de Huamanga, 146-147).

The hole cited in the text of Quispe Andia, the ceremonial hole in the corner of the farm, stands for Mother Earth’s mouth. Thus food becomes an essential part of the ritual of pleasing Mother Earth to give thanks for the harvest and ensure future prosperity.

To feed the earth is an act of indispensable reciprocity, because it is Mother Earth who provides us with food each and every day. In Ayacucho, as in the Japanese paradise of Tenri, eternal joy is based on this exchange of affection and solidarity.

La Comida de los Dioses

Por Luis Millones

Una pintura en estilo tradicional del pueblo de Sahua, Ayacucho. La escena representa el banquete de montañas que rodean el pueblo. La figura central es la montaña Mariano Borao que protege la comunidad, y las otras figuras son las montañas vecinas o las apus. Pintura por La Asociación de los pintores de Sarhua/cortesía de Luis Millones.

A principio de la década de los noventa, viajé con frecuencia a Osaka. Los investigadores del Museo Etnográfico Nacional de Japón tenían como eje de su labor la sierra del Perú, y en especial Ayacucho, departamento de una larga y sufrida historia. Como parte de este equipo y en calidad de profesor invitado, se me abrieron las puertas de una sociedad que mostraba sus encantos día a día. A lo largo de mi estadía, descubrí que uno de mis colegas tenía una relación importante con el sacerdocio de la Iglesia de Tenrikyo. Me interesé por su religión y lo que aprendí de ella fue suficiente como para querer participar en el peregrinaje anual de sus creyentes, a la ciudad sagrada de Tenri, en la prefectura de Nara, región de Kansai. Por un corto período, Tenri había sido la capital del Imperio de Japón (488-498), y aún hoy es una ciudad hermosa y sede del culto de Tenrikyo.

El recorrido fue duro y fascinante; de lo mucho que conocí esos días, es pertinente recordar en esta ocasión lo que me respondieron cuando pregunté sobre lo que se comía en el Paraíso, o su equivalente al dogma cristiano. Para mi total sorpresa, el lugar de premio o Youkigurashi era un espacio similar al de castigo: un gran banquete, con viandas iguales en ambos lugares. Si se observaba con detalle, condenados y bienaventurados tenían para comer palillos de un tamaño desmesurado, y quienes estaban castigados lucían demacrados y padecían de hambre, mientras que los premiados aparecían rozagantes y bien nutridos. La explicación era simple para una fe que practica y enfatiza la solidaridad: mientras que los condenados intentaban comer cada uno de ellos con palillos de ese tamaño, y no acertaban a hacerlo, por su parte, los favorecidos por la divinidad aprovechaban la longitud de sus instrumentos para alimentarse uno al otro.

De regreso a tierras ayacuchanas, llevé la pregunta a mi trabajo de campo, recordando que en Huamanga estaría tan lejos del pensamiento occidental europeo como lo había estado en Tenri, cuando los sacerdotes bailaban en los recintos subterráneos del templo, para renovar la creación del universo.

Conocía las cosas escritas por los cronistas españoles o indígenas cristianizados de fines de siglo XVI y XVII. Las fuentes concuerdan en que los dioses andinos comían mullu, es decir conchas de mar (Spondylus), e incluso nuestra única fuente escrita en quechua nos recuerda que al masticar el sonido que hacían era «¡cap, cap!» rechinando los dientes mientras comían (Ávila 2007, 127).

Todavía hoy las conchas de mar, también las menos vistosas, tienen prestigio religioso; se les usa en las ceremonias como recipiente para absorber por la nariz los jugos de plantas alucinógenas, en otras regiones del Perú. Pero en Ayacucho, Cusco, y en general en la sierra peruana, alimentar a los dioses es un tema complicado.

En primer lugar, conviene aclarar que la evangelización cristiana destruyó toda imagen visible de las religiones precolombinas. Quedó incólume la geografía sagrada: el culto a la Tierra y a sus expresiones visibles, los cerros. A lo que hay que agregar las áreas de contacto con los seres humanos: las cuevas y los manantiales. Pero, además de la imposibilidad de borrar esta última forma de religiosidad, la persecución se detuvo porque el trabajo forzado de los indígenas era la fuente de riqueza del imperio español y todo hostigamiento a su labor perjudicaba su rendimiento. En el siglo XVIII, ya la sociedad andina había consolidado una estructura religiosa que reinterpreta la doctrina cristiana y la suma a las reminiscencias precolombinas, y que es el germen de la religión indígena que ahora conocemos. En ella, los dioses, es decir, la Madre Tierra y los cerros (apus o wamanis) deben recibir alimentos de sus muchos creyentes. Se los envían a través de una ceremonia que tiene por lo menos dos nombres en español quechuizado: pagapu y despacho. Así se alude a las razones primordiales de la ceremonia que vamos a describir: se paga a la Tierra y se despacha, es decir se envía lo que ella necesita. Si el oferente es un quechua hablante usará las voces apachiku, mallichi, kutichi, etc., en general las variaciones tienen relación con la composición de lo que se ofrece y del lugar en que se hace, que están vinculados con los intereses de quien o quienes van a alimentar a la Mama Pacha. Esto quiere decir que hay pagapus específicos para ser usados por ganaderos, los que necesitan agua de la lluvia o del caudal de los ríos, los que van a cazar animales silvestres, o aquellos que buscan de recobrar la salud, etc., etc.

Como dije líneas arriba, hay varias formas de preparar un pagapu, pero una de las más importantes es la que debe alimentar la Mama Pacha o Madre Tierra, para que nos asegure su generosidad al permitir que obtengamos buenas cosechas. Dejaré a continuación que don Juan Quispe Andia, nos relate desde Chungui, La Mar, Ayacucho, cómo se hace un pagapu:

«En las alturas de Chungui, cuando se va a cosechar papas, el dueño invita a todos sus vecinos para que le ayuden, todos van a ayudarle porque es ley, todos ayudan siempre. El dueño les da a cambio de la ayuda coca, trago, comida, y cuando toca a otro campesino cosechar, tiene que ir a pagar la ayuda que le ha dado. Por eso nadie deja de ayudar. Los vecinos van con toda la familia, los hombres son los cosechadores, las mujeres las pallapadoras y las que cocinan, los jóvenes son los ayudantes para trasladar y amontonar la papa. Se cosecha haciendo siempre bromas, a veces con música y si no, contando chistes, siempre con alegría, por los frutos que da la tierra. Cuando termina la cosecha, las papas se guardan en la casa del dueño, pero primero se escogen las que van a servir de semilla para la próxima siembra, y las papas que se han malogrado con las lampas. La dueña cocina para invitar a los comuneros la papa malograda al cosechar mientras los hombres guardan la papa y las semillas. Cuando ya han terminado, comen la papa cocinada con ají y sal, a veces con carne o algún picante que ha preparado la dueña y con la chicha y con el trago. Todos después chacchan su coca y fuman su cigarro. Entonces, todos se van menos el compadre del dueño. Ellos regresan a la chacra solos llevando las mejores papas, las más hermosas, para hacer el “pago” a la tierra para que les siga protegiendo. El compadre hace un hueco en un rincón de la chacra, de unos 50 o 60 centímetros y cuando ha hecho el hueco, le tinka con trago en forma de cruz y luego le hace la ofrenda de la papa, con su trago, generalmente un cuartito, un puñado de coca kinto, un par de cigarros, y luego lo tapa diciendo: Madre Tierra recibe la ofrenda de tus hijos para agradecerte la cosecha que mi compadre ha recogido y para que le sigas dando buena producción, por eso te pagamos para que tu abundancia nos des. Luego regresan a la casa y el dueño invita a su compadre a tomar y comer. Pero durante el “pago” el dueño no dice nada, todo lo dice el compadre que hace de intermediario para que acepte la tierra» (Delgado Sumar 1984, 146-147).

Cabe algunas aclaraciones: 1) coca (Erithroxylum coca) es el arbusto cuyas hojas mantienen su carácter sagrado y son el signo de respeto en las relaciones interpersonales. Chaccchar es masticar las hojas con una pasta hecha de ceniza de vegetales que se denomina generalmente lluqta. Al mezclarse con la saliva produce la sensación de revigorizar al consumidor, anulando el cansancio. 2) Trago: alcohol industrial puro, diluido con tres volúmenes de agua hervida con semillas de anís y otras plantas, a lo que se agrega azúcar. 3) Pallapadoras proviene del quechua pallay, que significa ‘recoger’. Son mujeres habitualmente jóvenes que colaboran en la cosecha. 4) Tinka: rociar con el dedo índice un poco de chicha o licor, del vaso que se va a beber. 5) Cuartito: vaso pequeño o porción pequeña de licor.

El texto de Quispe Andia no necesita mayores explicaciones, el hueco «en un rincón de la chacra» en general es interpretado como «boca» de la Madre Tierra y al alimentarla, la familia agradece la cosecha y asegura prosperidad futura.

Fall 2014, Volume XIV, Number 1

Luis Millones, the 2002-2003 Robert F. Kennedy Visiting Professor at Harvard, is the Director of the Fondo Editorial de la Asamblea Nacional de Rectores del Perú. He is Professor Emeritus at the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. In 2006, he held the Andrés Bello Chair in Latin American Civilization at New York University.

Luis Millones, Doctor en Letras (Historia) por la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (1965) y Profesor Emérito de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, es Director del Fondo Editorial de la Asamblea Nacional de Rectores del Perú en la actualidad.

Related Articles

The Violence of the VIP Boxes

English + Español

In Peru, the upper class does not like to mix with those they consider different or inferior. Their maids on the beaches south of Lima are not allowed to swim in club pools and, sometimes, not even in the ocean. The VIP boxes at sports and theater events maintained by the government are a public display of a private practice that reproduces in the public sphere the worst aspect of private hierarchical structuring.

Peace and Reconciliation

English + Español

Eleven years have gone by since the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission presented its final report. The report reconstructed the history of many cases of massacres, tortures, murders and other serious crimes. At the same time, it contributed an interpretation of the…

I Ask for Justice: Maya Women, Dictators, and Crime in Guatemala, 1898–1944

On May 10, 2013, General Efraín Ríos Montt sat before a packed courtroom in Guatemala City listening to a three-judge panel convict him of genocide and crimes against humanity. The conviction, which mandated an 80-year prison sentence for the octogenarian, followed five weeks of hearings that included testimony by more than 90 survivors from the Ixil region of the department of El Quiché, experts from a range of academic fields, and military officials.