The Guarani and the Iguaçu National Park

An Environmental History

The Iguazu/Iguaçu National Park spans the Argentine-Brazilian border, but the center of attention is the mighty Iguazu/Iguaçu Falls.

In September 2005, a group of 55 Guarani Indians occupied a forested section of the Iguaçu National Park in the state of Paraná in southern Brazil. You may recognize Iguaçu as a park and tourist destination on the Brazilian side of the famous Iguazu Falls. However, it also protects 400,000 acres of Atlantic forest, one of the last large continuous stretches of this endangered biome. The Guarani came from the overcrowded Ocoí reservation on the shores of the Itaipu reservoir, some twenty miles from the park where they lived. Chief Simão Tupã Vilialva said the group intended to use the occupation to pressure the Fundação Nacional do Índio (FUNAI), the Brazilian Agency for Indian Affairs, into solving their land shortage problem. Through the occupation of Brazil’s most visited national park, the Guarani demanded a solution for the dozens of families whose land was encroached by farmers and the Itaipu lake in the 570-acre Ocoí reservation.

The Guarani remained in the Iguaçu National Park for eighty days, only agreeing to leave after being promised by FUNAI officials to be taken to Guarapuava, headquarters for the FUNAI office for Western Paraná. They wanted a face-to-face meeting with FUNAI officials to present their demands for new land. FUNAI brought in a bus to transport the Guarani, but instead of heading to Guarapuava, the driver took them to another reservation, Tekohá Añetete, in Diamante do Oeste. There, FUNAI officials planned to cram the 55 Guarani in an existing and already overcrowded reservation shared with other indigenous groups. Perceiving FUNAI’s deception, the group led by Vilialva was infuriated. As they were getting off the bus, a clash took place between the Guarani and state officials; a police officer was shot with a Guarani arrow. Eventually Itaipu Binacional, the company behind the hydroeletric dam, decided to intervene and acquired a new 600-acre area adjacent to the Tekohá Añetete reservation providing land for some of the Guarani families from Ocoí.

A couple of hundred acres did little to assuage the chronic land shortage suffered by the Guarani at the Ocoí reservation. In October 2013 a new group of eight individuals once again occupied the Iguaçu National Park. By the end of May, the group had swelled to 25. The Guarani who entered Iguaçu claimed their people had inhabited those forests, the Ka’ Aguy Guasú (big woods), before the park’s creation in 1939. They argued they were not responsible for the transformation of nature into soy plantations, grazing fields, factories, roads and cities. Therefore, they should not be penalized by exclusion from the last continuous stretch of Atlantic forest in Western Paraná. They demanded that part of the national park be declared an indigenous reservation, thereby correcting what they saw as a historical wrong committed by the Brazilian state when it created a protected area that barred indigenous peoples from the forest.

Were the Guarani from Ocoí correct in claiming they had lived in the area occupied by the national park before its creation? It depends on where one sets the threshold. Unquestionably, the Guarani and other indigenous groups like the Kaingang had lived in the area way before the creation of the national park. However, what is not clear from the historical record is whether they had been driven away from the territory of the park at the moment of its establishment by park authorities, or prior to that, by settlers.

Before beginning my research in the history of the Iguaçu National Park, I believed the Guarani would be a constant presence in the historical documents. After all, in the last three decades the historical scholarship on national parks has brought to light a common pattern of eviction of indigenous communities in the creation of protected areas devised to be devoid of people (but not tourists). So I believed I would find documents indicating Indian displacement in the creation of the national park. Instead, what I found was mostly silence. For the first decades of the park’s existence, hardly any source indicates the presence of Guarani or other indigenous groups in the park area. The first time they appear in park documents is in a 1967 memo by Renê Denizart Pockrandt, then the director of the Iguaçu National Park. Pockrandt suggested the indigenous peoples roaming the Argentine-Brazilian border be settled inside the Brazilian park as a touristic attraction, a suggestion that never became a reality.

Another type of evidence of the presence of Guarani within the limits of the park was provided by anthropologist Maria Lucia Brant Carvalho. In her Ph.D. dissertation, Carvalho inter-viewed Narcisa Tacua Catu de Almeida, a senior member of the Guarani community in Ocoí, who claimed to have lived in two different Guarani communities in the area encompassed by the park from 1934 to 1962. Almeida cites a first, violent eviction in 1943, followed by another in 1962. However, it is unclear who pushed the Guarani away from the park since park authorities had only tenuous control over its territory for the first thirty years. The park then existed mostly only on paper.

Brazilian authorities finally moved to enforce the Iguaçu National Park as a protected area in the 1970s, and nowadays the park stands as an island of rainforest surrounded by a sea of farming landscape. The park presents a significant area covered by old-growth forests, since sixty percent of its territory has been established as an “intangible area,” a designation banning human settlements and all types of human activities except for scientific research and surveillance. Park zoning allows more intensive human activities such as tourism in the remaining area, but it bans permanent dwellers and extractive activities. In this way, the Guarani claim to the park’s natural resources puts them at odds with environmental authorities whose mission is to keep a territory free of most types of human interventions.

Brazil established the Iguaçu National Park in 1939 following the creation of the Argentine Iguazú National Park on the other side of the border five years earlier. Both parks were intended to protect each side of the bi-national Iguazu Falls, the massive 1.7-mile-wide series of waterfalls located on the Iguazu River, at the border shared by the two countries. The parks also extended inland, sheltering more than 555,000 acres of the original Atlantic forest that, in the early 1940s, still covered most of the Brazilian southwest, Argentine extreme northeast, and the Paraguayan east. Eighty years of successive waves of colonization, mostly by Brazilians of European descent coming from Rio Grande do Sul and São Paulo, transformed what was a sparsely inhabited frontier of forests and mate gathering into an expanse of crop fields and mechanized farming. The region became a center for the green revolution transforming the Brazilian (and later Paraguayan) hinterland in the 1970s and 1980s. The two parks, therefore, contained the last large stretch of forest cover in the Triple Frontier, thus earning the status of UNESCO heritage sites in the 1980s.

The Iguaçu National Park in Brazil originated with the donation of an estate by the government of the state of Paraná that included the Iguazu Falls on the Brazilian side. The original proponents wanted to transform the area into a national park to guarantee Brazilian access to the waterfalls. From 1939 to 1944, the park was limited to the donated estate’s original 12,350 acres, but in 1944 the federal government decided to incorporate new land into the park to protect the forest from loggers, increasing its size to 400,000 acres. Large public land tracts comprised the bulk of the land used in the park expansion. However, there was a problem: for the expansion, the federal Forest Service used public land that was in judicial dispute between the Brazilian federal government and the state of Paraná.

The long court battle between state and federal governments ended with a 1963 Brazilian Supreme Court ruling in favor of the federal government. The decades-long juridical incertitude about who owned the national park’s public land, coupled with the land grabbing practices that plagued western Paraná, allowed hundreds of southern Brazilian migrants to acquire land and settle inside a section of the national park. In the 1970s the Brazilian military dictatorship decided for the costly and politically difficult removal of the 447 families (about 2,500 people) living inside the Iguaçu National Park. The great majority had arrived in the 1950s and 1960s, and they came to occupy seven percent of the park’s area. They had built farms, villages, schools, roads, and even a chapel inside the Brazilian park. After the eviction, infrastructure that could not be removed by the settlers was torn down by park authorities. Over the years, a secondary forest grew over most of the area formerly occupied by farms.

Inadvertently, the resettlement of these 447 families of white settlers served to reintroduce the Guarani into the history of the Iguaçu National Park. The area where the Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária (INCRA), the Brazilian agency for agrarian reform and colonization, chose to relocate settlers in the early 1970s already harbored a group of Guarani. Inside the chosen area was Jacutinga, a small Guarani community engaged in fishing and subsistence farming near the confluence of the Ocoí and Paraná Rivers. This Guarani community was not under the radar of FUNAI, and in its survey INCRA classified their members as squatters. In order to prepare the terrain to receive the settlers evicted from the Iguaçu National Park, INCRA started pressuring the Guarani to leave the Ocoí area. Many decided to flee to Paraguay or Argentina, but some resisted. The agency brought in henchmen to harass them, burning their houses and confiscating their fishing and agricultural tools.

INCRA’s attack on the Guarani drew the attention of a local human-rights activist, lawyer Antonio Vanderlei Moreira. In 1975 Moreira accused INCRA employees and their hired gunmen of threatening, assaulting and burning the houses of Guarani and peasants living in Ocoí. In 1977, a committee formed by INCRA and FUNAI officials was established to investigate the presence of Indians living inside the Ocoí estate. The 30,000-acre tract had been expropriated by INCRA in 1971 to receive the 2,500 settlers evicted from the national park. It was named Projeto Integrado de Colonização – Ocoí (PIC-OCOI), “Ocoí Integrated Colonization Project.” The INCRA-FUNAI committee found 27 Guarani living inside PIC-OCOI near the banks of the Paraná River. To accommodate these individuals they created the Ocoí reservation in another area inside PIC-OCOI. The small area set to be an Indian reservation had originally been designated as forest reserve for the incoming settlers. The Guarani ended up enclosed in a small reservation surrounded by the farmers relocated from the Iguaçu National Park.

In 1982, the creation of the Itaipu reservoir flooded part of PIC-OCOI, swallowing a big chunk of the land available for both the Guarani and the white settlers. The Guarani found themselves in a narrow, 570-acre swath of degraded forests on the banks of the new reservoir, trapped between the new lake and the relocated farmers. Life in such conditions was hard, and the Guarani suffered all sorts of environmental problems: erosion by lake waters, contamination of lake water by pesticides from neighboring farms, endemic malaria, and encroachment by the surrounding farms. At the same time, the population of the Ocoí reservation continued to increase due to natural growth and new arrivals from other Guarani communities. In 1986, the Guarani started a campaign for new lands and pressured the World Bank for a solution—the bank had financed the building of the Itaipu dam. They sent a Harvard-trained anthropologist, Shelton H. Davis, to assess the veracity of the Guarani claims. Davis’ report, along with a new report by Brazilian anthropologist Silvio Coelho dos Santos, president of the Brazilian Association of Anthropology, convinced Itaipu to work for solving the problem of the overcrowded reserve. The company acquired a 4,300-acre estate in Diamante do Oeste to accommodate the Guarani families from Ocoí. This was the same reservation to which the Guarani group occupying the park in 2005 would be deceitfully taken by FUNAI.

Guarani men hike on the trails to their camp inside the Iguaçu National Park in November 2013. Photo by Marcela Kropf.

The Guarani who entered the Iguaçu National Park for a second time in 2013 have already left the park, following a court order issued in August 2014. However, the overpopulation problem at the Ocoí reservation, where about 600 hundred people share 570 acres, still persists. The existence of a protected area containing the last large remnant of Atlantic forest in the region became a point of contention between environmental authorities and indigenous groups. What the former see as crucial reserve of a dwindling biome, the latter see as the retention of natural resources that should be made available to the region’s indigenous peoples. Yet, after recogniz-ing the difficulty in changing an environmentalist paradigm that sees national parks as an off-limits territory for people, the Guarani, by resorting to occupations, have turned the park into an instrument for leveraging their position in their struggle for access to land.

Spring 2015, Volume XIV, Number 3

Frederico Freitas is a PhD. candidate in Latin American History at Stanford University. His research focuses on the environmental history of the border between Brazil and Argentina in the twentieth century, and the creation of the two national parks of Iguaçu, in Brazil, and Iguazú, in Argentina.

Related Articles

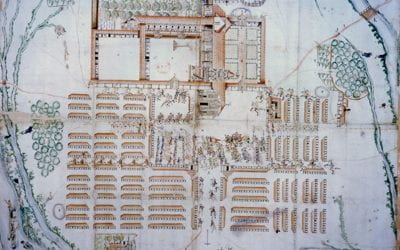

Jesuit Reflections on their Overseas Missions

When you think of Jesuits in their missions around the world, you—the casual reader—might not think of Plato or ancient Greek authors. Yet two of these…

Paraguay: Un país en una lengua misteriosa y singular

English + Español

If you arrived in a country where almost 90% of the inhabitants speak Guarani, an official and national language along with Spanish but do not identify themselves as “Indian” or aboriginal…

Territory Guarani: Editor’s Letter

DRCLAS receptions are bustling affairs, sparkling with ample liquor, Latin American tidbits and compelling conversations. It was at one of these receptions that Jorge Silvetti and Graciela Silvestri first approached me casually regarding an issue about the Guarani…